The current political emphasis on greater accessibility and public engagement in relation to urban nature raises certain difficulties. Professional botanists, entomologists and other scientists tell me that public policy towards biodiversity and the protection of “wild nature” is being driven increasingly by a public-relations emphasis on certain “flagship species” or vague notions of sustainability rather than detailed knowledge about sites, species and the ecological dynamics of urban space. Those agencies charged with the protection of nature or the fostering of environmental education often lack any specialist expertise leading to a repeated emphasis on a small number of easily recognizable animals or plants. The idea that deeper knowledge requires years of patience and dedication has been supplanted by a culture of immediacy. In such circumstances how can cultural or scientific complexity be effectively communicated? What happens when autonomous criteria for scientific evaluation conflict with externally imposed agendas for reshaping knowledge? The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls for the defence of the “inherent esotericism of all cutting-edge research” yet he also insists on the development of appropriate strategies for the scientific enrichment of the public realm.1 In the case of urban ecology there is a glaring disjuncture between specialized scientific understandings of urban space and mediated discourses of consumption.

Category: blog

To open a wasteland

The Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui has a wonderful photo entitled “To open a wasteland” that depicts some kids rushing into a patch of waste ground in Brussels. The sense of an urban enclosure being revoked is captured in the blurred movement of figures surging forward.

I think I first reflected on the presence of “enclosed” waste spaces in cities whilst writing about Lucien Freud’s Wasteground with Houses, Paddington (1970-2) which provides a view from the window of his West London studio. Freud depicts the rear elevation of shabby Victorian terraces, with their jumble of aerials and chimneypots, interspersed with an area of overgrown wasteland. So precise is his painting that we can identify many of the plants he observes.

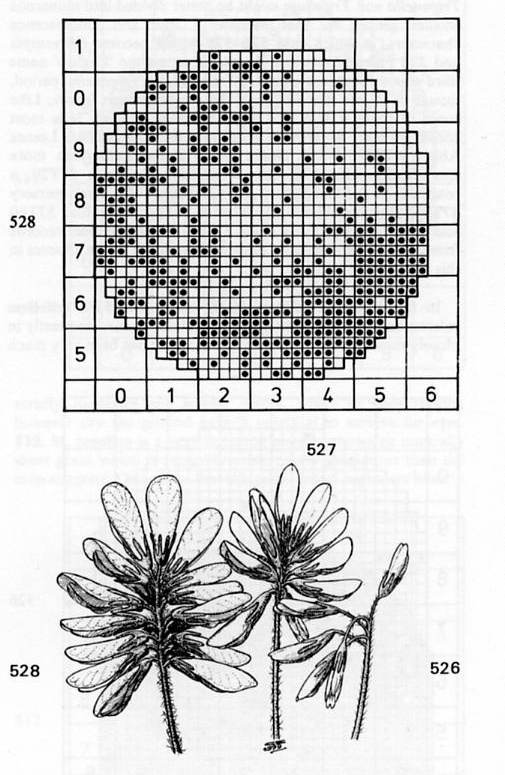

From my office window at UCL in central London a few years ago I noticed a similar anomalous space that had developed spontaneously between other buildings. As I looked down one winter afternoon a fox sauntered past and in summer the honey-scented flowers of Buddleia davidii are visited by bees and butterflies. This summer I decided to pursue my curiosity further and arrange access to the site. After opening a metal gate I made my way up some slippery rubbish-strewn steps and entered a strange world of tangled vegetation. Accompanied by the artist Carolyn Deby and the botanist Nick Bertrand we surveyed the site, finding over thirty species of plants, including three kinds of oak trees. Nick’s expertise was inspirational as he pointed out different species that had colonized the site. A seemingly empty space was brimming with life.

What struck me immediately was that this space has become a kind of miniature urban forest with its own mix of plants from all over the world. Instead of looking down onto the site I was now looking up at the brutalist façade of the university building with leaves touching my face. For a moment I became aware of myself at another point in time gazing distractedly from my window just metres away.

This afternoon, however, I glanced towards the site and noticed that it has just been cleared, leaving an expanse of rubble with a few plants left where they could not be scraped away by heavy machinery. The cycle of entropy and ecological succession must begin anew amid the vagaries of urban development and yet another planning application.