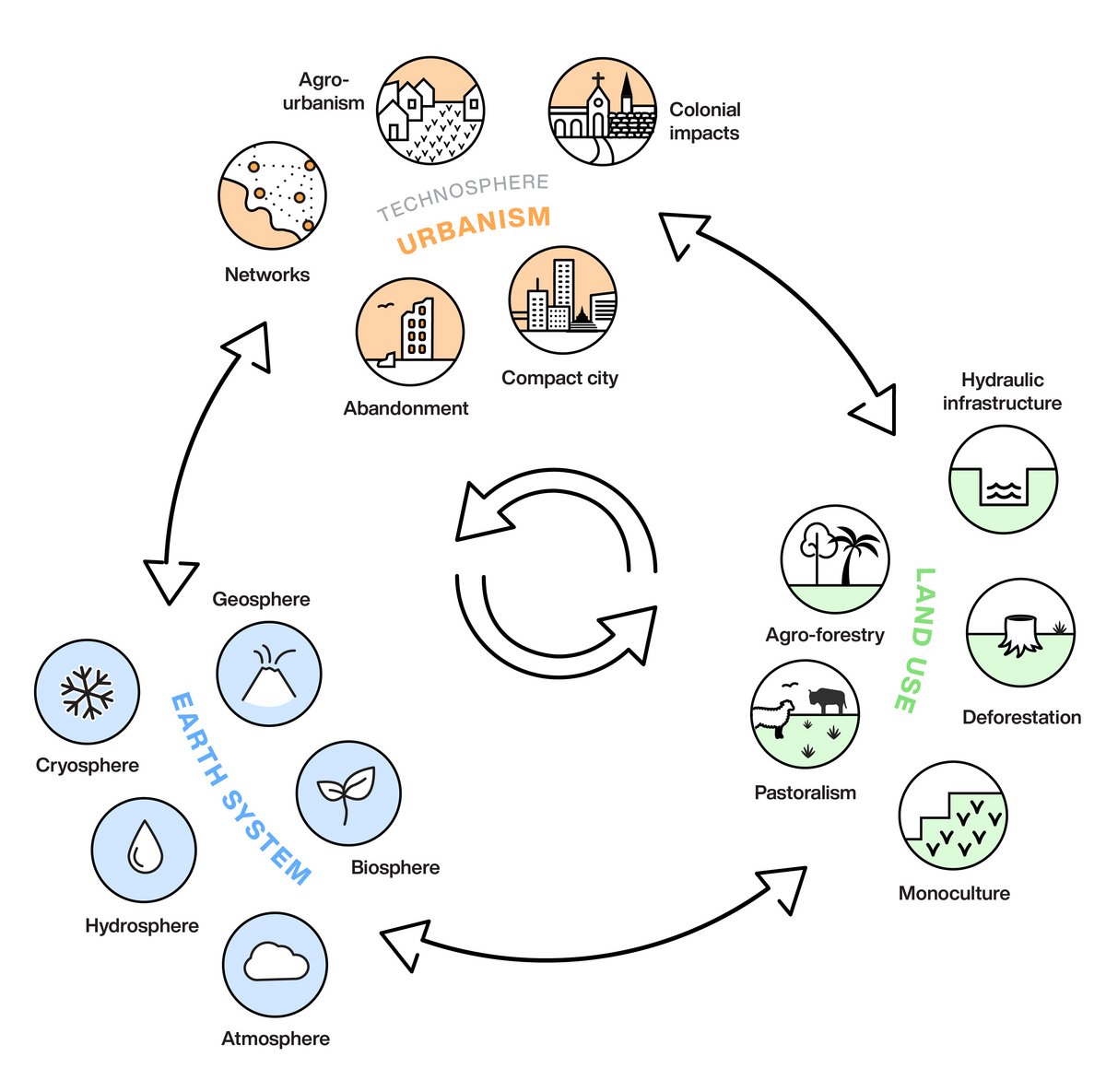

At a recent workshop entitled “Connecting urbanism across time and space” led by urban archaeologists at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany, one of the participants offered a definition of the urban as “looking for the edges of built infrastructure”. A number of the presenters used remote sensing methods to reveal traces of past cities through signs of abandoned buildings, water collection and distribution systems, or other cultural artefacts. The workshop organizers were keen to identify the common determinants of urban form that might render archaeological knowledge useful for contemporary concerns with urban resilience, as shown in the figure drawn by Michelle O’Reilly that I have used to illustrate my text. Some contributors were keen to stress how the field of “urban science” might lead to the closer integration of urban research across diverse historical and geographical contexts. There was a recurring emphasis on cities as a particular kind of complex adaptive system that is amenable to advanced forms of modelling, including the application of AI enhanced capacities for the collection, storage, and analysis of data. One participant from a biosciences background explored the social behaviour of insects as a basis from which to study human settlements in terms of behavioural algorithms. In my own presentation on “urban metabolism,” however, I offered a working definition of the city that I had written down while listening to the other presentations. I suggested that “a city denotes a certain kind of cultural and political configuration that is associated with but not necessarily determined by a series of material and topographic parameters.” I highlighted problems with an attempted epistemological elision between the social and biological sciences, and introduced an alternative perspective based on the neo-Marxian concept of metabolic rift as a different kind of analytical schema.