Alfonso Cuarón’s film Roma (2018), named after the eponymous neighbourhood of Mexico City, is framed through the experience of a middle class family’s maid Cleo (played by Yalitza Aparicio Martínez). The film evokes an intense sense of time and place from the early 1970s inspired byCuarón’s childhood memories. The set design encompasses specific details such as tile patterns along with the use of black and white photography and rich soundscapes to lend the film an especially poignant atmosphere. The narrative weaves together the emotional turbulence of the main protagonists with wider events such as the Corpus Christi massacre of university students of June 1971. Roma provides a subtle exploration of the intersections between place, politics, and memory, incorporating the claustrophobic drama of a family in crisis, as well as the stark social divisions that underpin modern Mexico. Cuaron’s Roma reminds us why cinema can be both aesthetically and politically compelling.

Tag: Places and Spaces

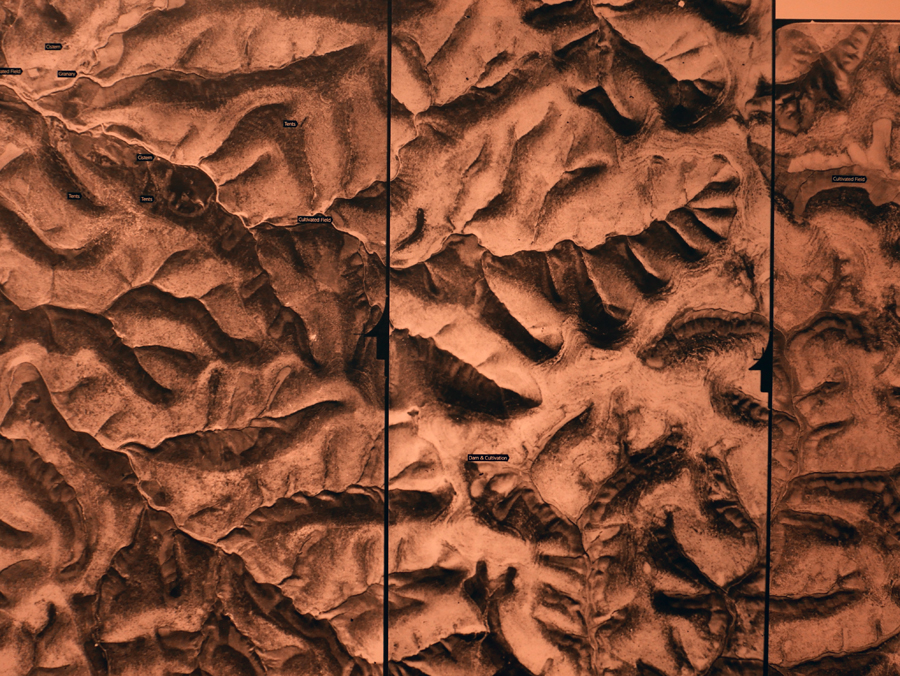

Truth is out there: Forensic Architecture

“In my understanding,” argues the founder of Forensic Architecture Eyal Weizman, “truth is something that is like a common resource”. “The truth is just like air or water,” continues Weizman, “something that we all need in order to understand, that provides evidence for civil society groups that are confronting state crimes and human rights violations worldwide.” In this brief yet eloquent interview, that accompanies Forensic Architecture’s short listed entry to the 2018 Turner Prize, we gain some fascinating insights into this radical interdisciplinary research programme that Weizman initiated at Goldsmiths over a decade ago. This remarkable body of work brings questions of epistemology and politics into dialogue as part of an unsettling of the human subject within architecture, art history, and related fields.

The work of Weizman and his colleagues provokes a series of critical questions that offer an important alternative to the recent emphasis on neo-vitalist or object-oriented ontologies:

i) An enriched reconceptualization of the human subject can transcend the limitations of humanism as well as the flattening and undifferentiated dimensions to some post-humanist perspectives.

ii) The conceptualization of buildings and also plants as evidentiary markers or sentinels could surely be extended to other organisms such as insects because of their extremely precise responses to environmental change. There is in this sense an interesting parallel with the emergence of “forensic entomology” and the use of biological data in criminal investigations.

iii) The radical use of technological tools, and the democratization of digital cartographies and other modes of representation, opens up new possibilities for articulating technologically enhanced forms of citizenship.

iv) The idea of truth as a collaborative synthesis derived from multiple perspectives, whose modes of scrutiny or validation are transparent, is a welcome foil to more cynical, nihilistic, or post-truth formulations. There is an emphasis on the accountability of science rather than its degree of fallibility or infallibility.

Wisconsin

In Michelle Obama’s eloquent speech given in New Hampshire against the rising tide of hatred and misogyny unleashed during the American election campaign she did not refer to Donald J. Trump by name but merely as Hillary Clinton’s opponent. Now we will have to get used to reading and saying his name more often but politics is never just a matter of a single individual, even under the extreme reactionary swerve of US politics, that has taken everyone, not only Americans, into a dangerously uncertain and perhaps even irreversible situation. The Paris climate change treaty may be in jeopardy. Key domestic achievements of the Obama years could be ripped up including wider access to health care. New appointments to the US Supreme Court will have lasting significance for American society.

The Democrats had foolishly assumed that Wisconsin was safely in their camp but the primaries had already given signs of deep disenchantment with the dynastic Clinton party machine. However effectively Hillary Clinton managed to present her own agenda she was nonetheless unable to completely emerge from the shadows of the last Clinton administration (as may also have been the case with Al Gore in 2000). Both Gore and Clinton were ultimately ahead in the popular vote but cursed by the final outcome of the electoral college system (and also in Gore’s case by the infamous Florida count and its legal aftermath). It turned out that Barack Obama’s broad-based coalition of progressive voters simply could not be mobilized in sufficient numbers to hold Wisconsin along with other crucial electoral college votes spread across the so-called “rust belt” of the Mid West. Would a Sanders-Warren ticket have done better? Maybe, but we shall never know. Furthermore, with over forty per cent of American adults not participating in the election, let alone a further seven per cent disqualified as former felons or for missing papers, the actual outcome of this debacle was decided by less than a quarter of the adult population, and far fewer if we look at the wafer thin margins in five or six bell weather states.

The rise of right-wing populism now endangers liberal democracy at a global scale. A toxic brew of pervasive inequalities, manipulated grievances, and historical amnesia threatens to overwhelm attempts to articulate a progressive alternative. The social democratic tradition in particular finds itself in deep crisis, its sources of mobilization splintered and scattered, and its previous achievements steadily eroded.

Harlow as viewed from Berlin

In the wake of the EU referendum there has been a surge of racism and xenophobia across the UK including acts of extreme violence. A spate of attacks on Polish people in the Essex town of Harlow, for example, located not far from London, culminated in the murder of Arkadiusz Jóźwik, and has attracted international attention. Unlike the muted media coverage in the UK external observers see this murder and the atmosphere of intimidation as a shameful indictment of the UK’s declining status as a respected European nation.¹

Harlow was the future once. As one of the original new towns established under the New Towns Act of 1946, and designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd, Harlow was a state-of-the art planned settlement created in response to acute overcrowding in London. Its buildings exemplify some of the most important examples of post-war British architecture and its comprehensive park system reflects the richness and complexity of the local topography.

Politically, Harlow is a classic bellwether constituency: Labour in the 1970s, Conservative in the 1980s, regained by New Labour in the 1990s, lost again to the Conservatives in the 2010 general election. In the 2015 election this working-class seat seems to have slipped further out of Labour’s reach than ever before: it is more Tory now than even under the high water mark of Thatcherism in the late 1980s. Without Labour winning Harlow there will probably never be another progressive government in the UK again.

Part of the UK’s problem is that it has never gone through a process of collective self-reflection over its colonial antecedents, whether in Ireland, Kenya, India, or elsewhere. A fog of self delusion pervades national discourse so that the UK’s complicity in the geo-political turmoil that has generated the contemporary mass movement of migrants and refugees is scarcely acknowledged. Equally, the enormous contribution of migrants to British society, over many decades, has been drowned out by years of wilful misrepresentation. The imperial mantra of “free trade” has become part of the labyrinthine tautology of “Brexit means Brexit” where vacuity and mendacity rule supreme.

The fading of Harlow’s post-war dream is a poignant cipher for the wider ills of British society. But the European Union is no more responsible for the town’s perceived decline than the rings of Saturn. Why blame Europeans for the failures of Britain’s ruling class? I hope very much that Neal Ascherson’s interpretation of the UK’s predicament is correct: we will spend three years trying to get out of the EU and then a further three years trying to get back in.²