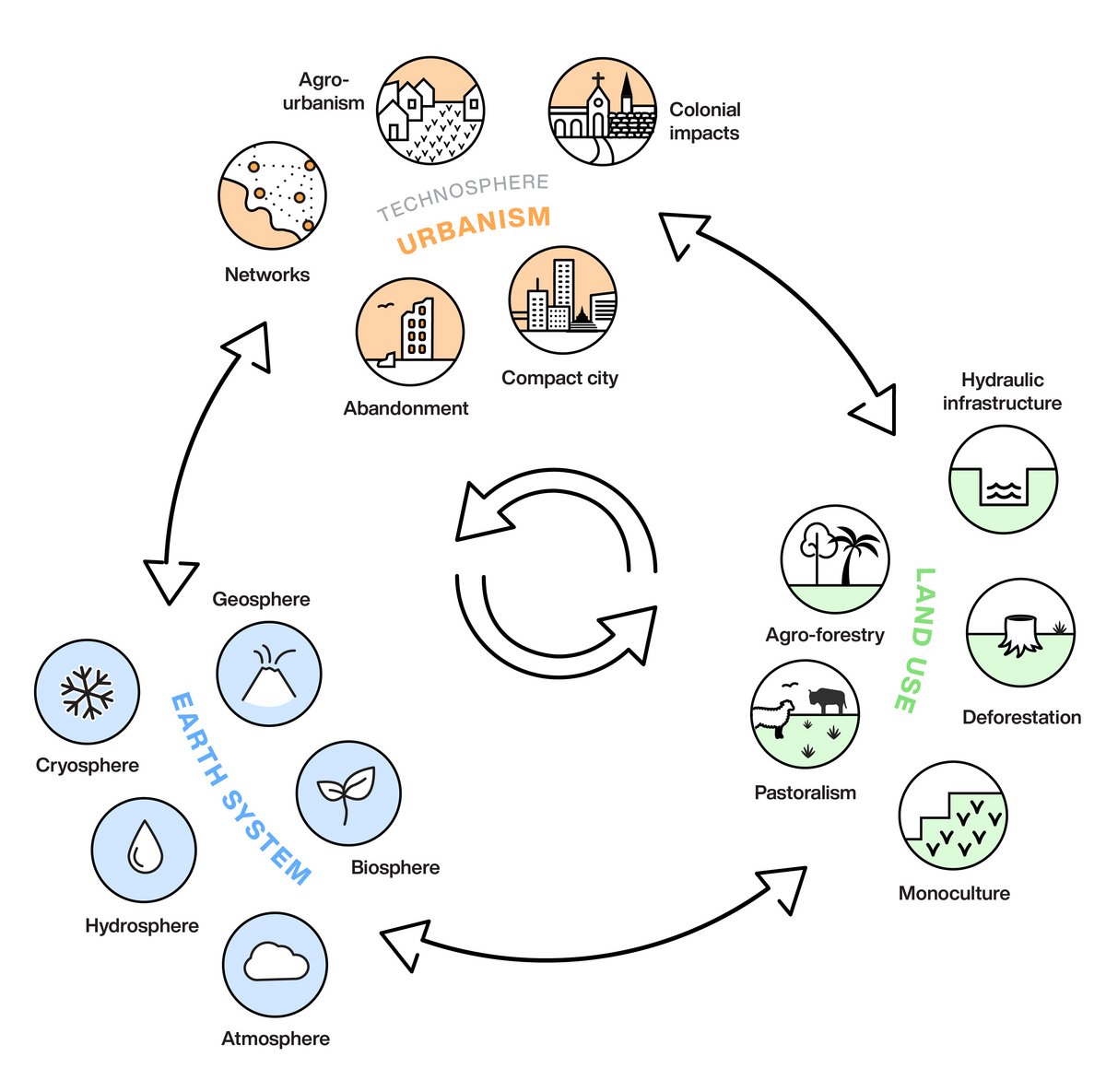

At a recent workshop entitled “Connecting urbanism across time and space” led by urban archaeologists at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany, one of the participants offered a definition of the urban as “looking for the edges of built infrastructure”. A number of the presenters used remote sensing methods to reveal traces of past cities through signs of abandoned buildings, water collection and distribution systems, or other cultural artefacts. The workshop organizers were keen to identify the common determinants of urban form that might render archaeological knowledge useful for contemporary concerns with urban resilience, as shown in the figure drawn by Michelle O’Reilly that I have used to illustrate my text. Some contributors were keen to stress how the field of “urban science” might lead to the closer integration of urban research across diverse historical and geographical contexts. There was a recurring emphasis on cities as a particular kind of complex adaptive system that is amenable to advanced forms of modelling, including the application of AI enhanced capacities for the collection, storage, and analysis of data. One participant from a biosciences background explored the social behaviour of insects as a basis from which to study human settlements in terms of behavioural algorithms. In my own presentation on “urban metabolism,” however, I offered a working definition of the city that I had written down while listening to the other presentations. I suggested that “a city denotes a certain kind of cultural and political configuration that is associated with but not necessarily determined by a series of material and topographic parameters.” I highlighted problems with an attempted epistemological elision between the social and biological sciences, and introduced an alternative perspective based on the neo-Marxian concept of metabolic rift as a different kind of analytical schema.

Author: Matthew

Plant Life podcast

Interview with Miriam Nielsen in Berlin for the Plant Life podcast series (in English and Danish)

On falling

The film On falling (2024), written and directed by Laura Carreira, explores the life of a Portuguese migrant Aurora (played by Joana Santos), who works long hours as a “picker” in a large warehouse on the outskirts of Edinburgh. Every move she makes in her working day for this Amazon-like company is electronically monitored so that any slowdown in her work rate attracts management attention. The pay is so low that the cost of repairing her mobile phone causes her to suffer acute hunger as well as the intense shame of missing a contribution to the electricity meter for her shared house (she lies completely still and cold in her darkened room hoping that no one notices her presence). Her phone has been her only thread of connection to a parallel reality that seems to offer some fleeting distraction from her intense loneliness. What is especially compelling about this film is that most of the people she encounters are kind: a generous Polish migrant in her house; a cosmetic store employee who applies some free eye shadow, wishing her well for what will be failed job interview; and the older park employee who finds her slumped among autumn leaves, and comforts her as she regains consciousness. To the global company she is merely a fragment of exchangeable code, a human robot who must endlessly rove the aisles to collect and scan products for people that she will never meet. On falling is the most astute cinematic portrayal of the algorithmic economy that I have seen.

The Brachen of Berlin

In Moss, T. (ed.) Grounding Berlin: ecologies of a technopolis, 1871 to the present (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press) pp. 343–360.

Microbiome

In Elinoff, E. and Rubaii, K. (eds) The social properties of concrete (Santara Barbara: Punctum Books) pp. 295-303.

From Dartford to Ballymena

In the local elections of 1 May 2025 the far-right Reform UK party gained control of 10 local authorities across Britain, including Kent County Council, which recorded the largest political swing of all. The town of Dartford, for instance, that has served as a political “bellwether” over many decades, saw a dramatic switch from Labour to Reform. The failure of “mainstream” politicians to challenge anti-migrant propaganda, and in many cases merely emulate it, has given unprecedented credence to racism and ethnic chauvinism, as community after community have fallen under the control of a new cadre of extreme right-wing politicians. The political endgame here is “re-migration” — a term that now resonates across many European countries — based on the expulsion of people of colour from “authentic” white-dominated British communities.

It is instructive that Reform has initiated a political alliance with the TUV (Traditional Unionist Voice) in Northern Ireland as part of a broader strategy to advance xenophobic politics across the whole of the UK. The TUV is implacably opposed to the Good Friday Northern Ireland Agreement of 1998 and won the 2024 parliamentary election for North Antrim where migrants in Ballymena and elsewhere are being harassed and firebombed out of their homes under what can only be described as ethnic cleansing taking place on the streets of the United Kingdom. Thus far these events have received limited media interest (Channel 4 News being an important exception) and have barely featured within national politics.

In the local elections of 2006, the far-right British National Party, whose political programme included exiting the European Union, elected 12 councillors in Barking, east London. The local Labour Party mobilized very effectively against the threat, and in the local elections of 2010 the BNP was vanquished from its temporary powerbase. Where is the parallel political campaign now to see off the far-right threat across Britain? Why the timidity and ineptitude of the new Labour government in the face of real and growing racist threats to society? Why has the anti-migrant rhetoric of the far right been increasingly adopted across the political spectrum, thereby paving the way for further political gains for extremist voices in society?

Urban political ecology as an expanded field

Dialogues in Urban Research

Ex Libris: books, creativity and academic freedom

Area

Urban metabolism redux

Urban Studies

All we imagine as light

Payal Kapadia’s new film All we imagine as light (2024) is an extraordinary meditation on urban life in contemporary India. The mobile and panoramic cinematography conveys the full scale of Mumbai as a kind of affective phantasmagoria. Mumbai is well known of course as a “cinematic city” but All we imagine as light is something quite different from more familiar genres of Indian cinema. The film presents a subtle and compelling drama focused on the lives of two nurses, Prabha and Anu, and a cook, Parvathy, who work at a hospital in Mumbai. The use of nocturnal urban landscapes and rich sonic textures provides an emotional depth to the relations between different characters, their longing for distant others, and their sense of alienation from the city around them. “Some people call this the city of dreams; I think it is the city of illusions. You have to believe the illusion, or else you go mad.”

Interestingly, the film is a co-production between France, India, Netherlands, Luxembourg and Italy, thereby mirroring some of the earlier important international collaborations that have supported key developments in global cinema, such as Japan in the early 1960s. It is the first Indian film to win the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival and the critics panel for Sight & Sound also named it the best film of 2024.

Four urban ecologies: a working typlogy and alternative conceptual synthesis

The politics of retribution

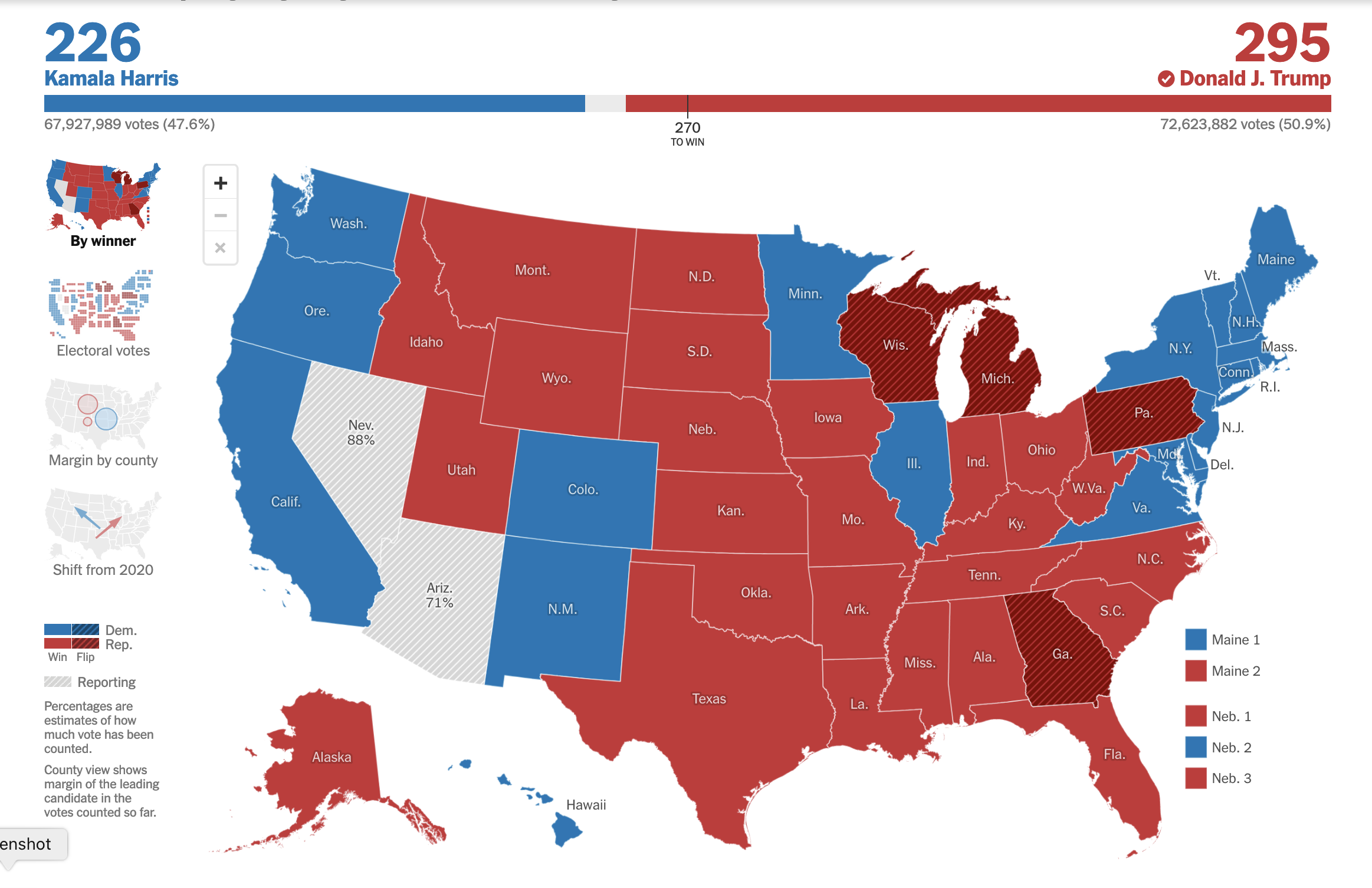

Trump’s decisive victory in the 2024 US Presidential elections is disturbing yet not surprising. He has steadily entered the American psyche and now sits at the centre of its political system for a second time. In a symbolic turn of events on election night it was the state of Wisconsin that tipped Trump over the threshold of victory in the electoral college, in a repeat of his unexpected defeat of Clinton back in 2016.

The reasons for his victory include persistent and growing socio-economic inequalities that have fuelled a toxic politics of retribution. The failure of progressive politicians to counter the pervasive myth that migration has caused declining living standards rather than the structural causes of inequality within capitalism has enabled rising levels of racism and intolerance almost everywhere. Trump’s victory is indicative of new forms of reactionary intersectionality between toxic masculinity and religious bigotry that mirror political trends in Brazil, the Philippines, and elsewhere.

A dark media ecology has been swirling with lies and misinformation for years, seeping into almost every dimension of public culture. Trump’s victory is in no small measure due to the high-profile support of Elon Musk in a further advance for techno-feudalism, the fossil fuel industry, and oligopolistic elites. The spectacle of Musk handing out cash prizes to Trump supporters on stage is reminiscent of the dystopian world of Darren Aronofsky’s film Requiem for a dream (2000) where the American dream has turned into a form of nihilistic desperation. Trump’s victory will undoubtedly prove to be a “swindle of fulfilment” in Ernst Bloch’s words.

Interview in Urban Regeneration (2024)

Interview with Dr Li Fan (TU Berlin) on 8 February 2024 in Urban Regeneration journal (in Chinese)

Losing control: REF 2029 and the downgrading of academic outputs

Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers

Attentive observation: walking, listening, staying put

Annals of the American Association of Geographers

Forensic ecologies and the botanical city

An urban political ecology of concrete

Roadsides 11

Urban ecology podcast (2024)

Podcast with Caroline Eleanor Devine at Columbia University, New York (recorded 21 April 2024)

https://www.geog.cam.ac.uk/files/people/gandy/Urban_Ecology_Podcast_Matthew_Gandy.mp4

Searching for Sebald

On my first ever trip to Antwerp last week I made a literary pilgrimage to the Centraal Station to see one of the inspirations for W.G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz. For Sebald, this ornate building, designed by Louis Delacenserie, and constructed between 1895 and 1905, displays an intense form of architectural eclecticism. The station’s elaborate interior serves as a cathedral to Belgium’s colonial past, a kind of architectural homage to “the deities of the nineteenth century – mining, industry, transport, trade and capital.” Standing in the entrance hall where Sebald’s protagonist Austerlitz once stood I reflect on the intricate coordination of space and time that underpinned the rise of European modernity. Spectral traces of violence have been transmuted into an edifice of marble and gold leaf, scarcely noticed by hurrying passengers. On the other side of the entrance hall there is a cavernous roof of steel and glass, its immense height built to accommodate steam trains. I order a coffee at le Royal café and wonder if Sebald might once have sat here making notes, listening to the swirling sounds of voices and trains.

Zany beetroot: architecture, autopoiesis, and the spatial formations of late capital

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 41 (6) pp. 1058–1074

The parking lots of Tallinn: an encounter with marginal ecologies

Roadsides 10

What is urban nature? Matthew Gandy in conversation with Dorothee Brantz (2023)

What is urban nature? Matthew Gandy in conversation Dorothee Brantz (recorded 15 June 2023). The film was made by Tobi Jaal and organized by the Hamburg Institute for Advanced Study.

Great Yarmouth

In Great Yarmouth: Provisional Figures (2023) the Portuguese film director Marco Martins provides a devastating portrayal of post-Brexit Britain and the precarious lives of migrant workers. The screenplay draws on the testimony of former workers and is unsparing in its depiction of their humiliating conditions. The focal point of the film is a blood-soaked turkey processing plant where English workers are no longer prepared to do the dirty jobs. In one scene we see newly arrived Portuguese workers having their teeth and hands checked, in another they are huddled in the cold before dawn, waiting for a bus to transport them to the factory. The central character Tânia (played by Beatriz Batarda) is a former worker who has become a kind of gang master overseeing the needs of the migrants. She has been saving money by overcharging them for their dilapidated housing but she is swindled in turn by one of the workers, leaving her life in ruins. The scenes of live turkeys in crates arriving for slaughter are reminiscent of the startling realism in Charles Burnett’s classic depiction of a modern abattoir in Killer of Sheep (1978). The brutal fate of these bedraggled birds, anxiously peering towards the camera, underlines a generalized sense of hopelessness. The only counterpoint to the nihilistic mise-en-scène is a former nature reserve worker, now a virtual outcast, who has befriended Tânia. In a poignant moment he cradles an injured greenfinch and also lets her hold the bird. The films closes with his voiceover, a childhood lullaby “ten for a bird you must not miss,” the double meaning evoking the aim of a hunter’s rifle or a heart that cannot grieve.

Chennai flyways: birds, biodiversity, and ecological decay

Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space

How to blow up a pipeline

The film How to blow up a pipeline (2022), directed by Daniel Goldhaber and inspired by Andreas Malm’s book, is one of the most important independent films of recent years. The plot centres around a meticulously planned operation by eight young environmental activists to blow up an oil pipeline in West Texas (the film was shot in New Mexico). As the film progresses we learn various elements of the activists’ back stories that have drawn them into taking part in a collective form of direct action such as the death of a family member to environmentally induced cancer or a sense of rage over oil extraction in ancestral lands. The film explores the moral dimensions to property destruction with great subtlety: indeed, part of their action involves turning off the flow of oil to prevent a spillage after destroying a section of infrastructure. The riveting screenplay has a real-time intensity that is reminiscent of John Cassavetes. As a cultural artefact in its own right it is film that is absolutely of its time as we enter the 2020s: a decade of deepening global environmental crisis for which our existing conceptual and analytical tools feel increasingly inadequate.

Interview with the Bentway magazine, Toronto (2023)

Matthew in conversation with Brian Sholis for the Bentway magazine, Toronto (recorded 12 July 2023):

https://thebentway.ca/stories/the-ecology-of-concrete-an-interview-with-matthew-gandy/

Urban political ecology versus ecological urbanism

In Kaïka, M.; Keil, R.; Mandler, T.; and Tzaninis, Y. (eds) Turning up the heat: urban political ecology for a climate emergency (Manchester: Manchester University Press) pp. 56–66.

Hermitix podcast: Natura urbana and urban ecology (2023)

Matthew in conversation with James Ellis for the Hermitix Podcast (recorded 24 May 2023):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0CUYWl5wSE

Grenfell

Steve McQueen’s short documentary simply entitled Grenfell is the most poignant artistic response that has yet been created to the fire that swept through the twenty-four storey Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 in which 72 people lost their lives. The film opens with a quasi-bucolic aerial panorama beyond the edge of London accompanied by intense ambient noise. Almost imperceptibly we are drawn very slowly towards the increasing density of metropolitan London: golf courses and gently curving suburban roads gradually give way to more tightly packed residential streets, signs of light industry, and the criss-crossing of roads and railway lines. As the helicopter-eye view moves ever closer to the group of West London hi-rise housing blocks the pale grey inhabited towers mark a striking juxtaposition with the blackened shell of Grenfell. The background noise fades to complete silence as we slowly begin to circle the charred exterior of the building. The blackened walls contrast with heat distorted materials and raw red patches. Rather than an architecture of trauma à la Daniel Liebeskind we are confronted with architecture as trauma. Filmed in December 2017 the winter light accentuates the combination of harsh colours and absence of life. The mood is meditative and shocking. Ever so gradually the camera begins to draw back. The subsonic shell of ambient sound returns as if the clarity of loss is now threatened by a kind of “white noise” in which memory, responsibility, and justice must jostle to be heard.

Books under threat: open access publishing and the neo-liberal academy

Zoonotic urbanisation: multispecies urbanism and the rescaling of urban epidemiology

Urban Studies

Sudan Archives

A sudden thunderbolt hit North London on the early evening of Monday 28th November leading to numerous enquiries about an unexplained explosion or even speculation about a meteor strike. What a fitting meteorological phenomenon to mark the arrival of the musician Sudan Archives in London for her show at the Electric Ballroom in Camden. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the violinist and songwriter Sudan Archives has crafted a genre defying body of work over recent years. Her show was marked by a sense of exuberance in its oscillation between searing violin improvisation and dramatic renditions of “Come meh way,” “Iceland Moss,” and other songs. Even if the somewhat muddy sound system could not convey the subtlety of all her works the atmosphere was electric. It is good to know that live music is flourishing once again in the post-Covid city.

Moths: the story of the butterfly of the night (2022)

BBC World Service broadcast 10/11 November 2022

The Forum with Matthew Gandy, Franziska Kohlt, Alma Solis, Liima Lember, and Shirley Camia

Arguments for a critical reading of urban landscapes

Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 81 (3) pp. 276–278

Political opportunism as hyper-parasitism

The UK is entering what may be the final act of an extended political farce that has been underway since the appointment of the disastrous David (“I’m giving up my time to govern”) Cameron in 2010. The appointment of Liz Truss as the fourth Conservative prime minister in a row after the departure of Boris Johnson brings a new level of self-serving mediocrity to British politics. Johnson, a populist opportunist, manipulated anti-European sentiment during the unnecessary EU referendum of 2016, in order to destroy the premiership of his Etonian rival, David Cameron. Johnson then worked assiduously to undermine Cameron’s hapless successor, Theresa (“breakfast means breakfast”) May. Now Johnson in his turn has been ousted in a further intensification of Tory in-fighting, the ageing membership having been lured towards the apparition of a Thatcher lookalike as his successor. No matter that Johnson has been replaced by another political opportunist, who campaigned to remain in the EU, but has successfully persuaded the increasingly right-wing membership of the Conservative party that she alone can carry the Brexit revolution forward. Of course, Brexit is not a political destination but a process, an ideological shark that must keep moving to stay alive as Fintan O’Toole and other commentators have pointed out. Although Johnson and Truss both claim that Brexit has been “done” it remains a poisonous mist that continues to infect all around it, damaging agriculture, manufacturing industry, trade, universities, and so on. In inheriting Johnson’s parliamentary majority Truss becomes a political hyper-opportunist feeding off the political capital of her predecessor. We should note that the phenomenon of hyper-parasitism in nature can takes complex ecological forms, with some plant galls displaying at least five levels of parasitism. Similarly, the emergence of political hyper-opportunism contains many layers of intrigue, and could be likened to a kind of political gall — shall we call it Brexit — since the definition of a gall is an “abnormal outgrowth” which can happen from time to time even in democracies.

Ghosts and monsters: reconstructing nature on the site of the Berlin Wall

Was für ein Phänomen ist das Urbane und wie können wir es kritisieren?

Sub\Urban: Zeitschrift für kritische Stadtforschung10 (1) pp. 158–160

Animals, territories, and environments (2022)

Event organized by the Committee on Environment, Geography and Urbanization at the University of Chicago with Neil Brenner, Victora Saramago, and Mindi Schneider on 29 April 2022.

Red ecologies: an encounter with the post-industrial landscapes of Esch-sur-Alzette

in Swinnen, P.; Peleman, D.; Heindrichs, N. and Van Houtte Alonso, B. (eds) Red Luxembourg (Köln: Walther und Franz König, 2022) pp. 147–175

Interview with Bloomberg CityLab (2022)

“The case for preserving spontaneous nature in cities.” Interview with Linda Poon, Bloomberg CityLab:

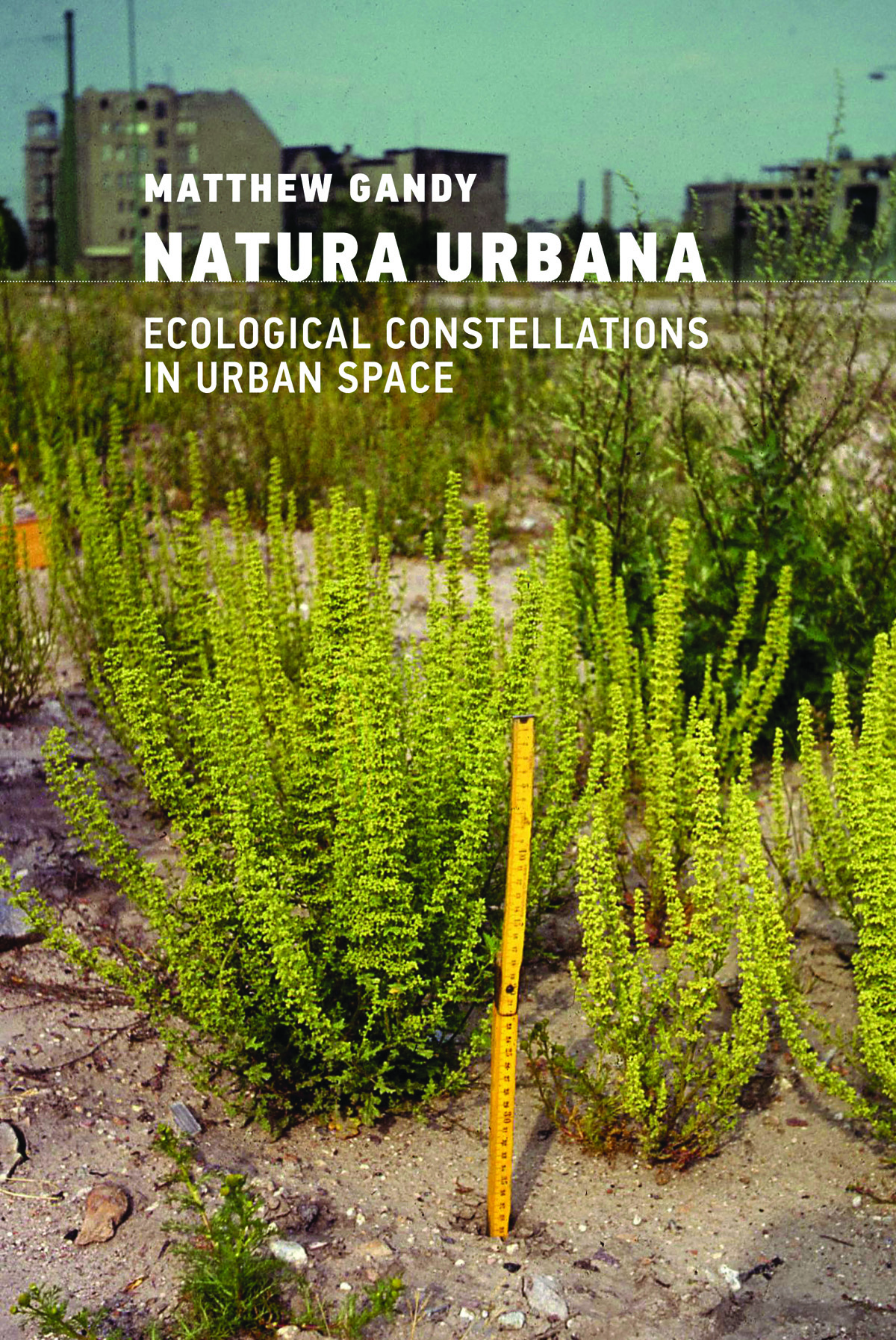

Natura urbana: urban constellations in urban space

Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press xiv + pp 416

Ukraine

On 3 March 2022 the Channel 4 News chief correspondent Alex Thomson, reporting from Moscow, made an astute observation about the Russian media landscape that “truth is not a concept, it’s a commodity”. Indeed, the attempt to control information through webs of power and patronage has been a hallmark of the Putin regime since its inception over twenty years ago. The invasion of Ukraine has been based on an attempt to alter history through the manipulation of truth. In this sense I follow the historian Richard Evans’s insistence that a relativist view of the past is dangerous and serves as a breeding ground for ethno-nationalist mobilization. Indeed, the Russian state’s attempt to manipulate global public opinion has been underway for many years, culminating in spectacular successes such as Brexit, the 2016 US Presidential elections, and support for (and from) a motley cast of politicians in France, Germany, Italy, the UK, and elsewhere. It is telling that Volodymyr Zelinskiy, when becoming president of Ukraine, did not request that pictures of himself be put up on the walls of government offices. Instead, he encouraged staff to display photos of their families (presumably including pets). It remains to be seen if the outcome of this terrible conflict will reset global politics towards democracy and away from the realm of violent autocrats and the wilful twisting of history in the geopolitical arena.

The zoonotic city: urban political ecology and the pandemic imaginary

The International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 46 (2) pp. 202–219

Read full text (PDF)

The politics of masks

Over recent months I have been working in Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich. Passengers on public transport systems are required to wear masks in order to protect themselves and others from infection with the Covid-19 virus. Not just any mask but a medical standard FFP2 design should be worn (see my photo from the Berlin U-Bahn). I have very rarely seen any passengers without masks apart from an occasional nose on display or the odd maskless mobile phone user (much to the irritation of other travellers).

In Germany the Covid-19 pandemic has focused attention on the need for competent science-led public policy marked by ambitious forms of large-scale governmental intervention to protect both public health and the economy. It is arguable that a political swerve towards calm deliberation and rational decision making may even have contributed towards the surprise outcome of the German federal elections last September when Angela Merkel was suceeded by Olaf Scholz as chancellor. More broadly, critical scholars such as Andreas Malm have asked whether the same level of seriousness in policy making might be applied to other threats such as climate change.

Whenever I return to London, however, I am shocked by the lack of compliance with public health measures. Although mask wearing remains compulsory on London’s public transport system perhaps only half of the passengers make any effort to comply. In the UK it appears that public health messaging has been steadily disintegrating for months, driven in part by the steady stream of revelations of rule breaking by law makers. In the place of clarity and cooperation a sense of confusion and cynicism has taken hold. It is worth recalling that some of the highest death rates from Covid-19 in the UK by occupation have been experienced by public transport workers and other front line staff who deliver essential services. To wear a mask is an act of solidarity with vulnerable workers as well as other passengers. The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has recently reiterated the requirement for people to wear masks on public transport but the police claim that they lack the resources to enforce these public health measures. Earlier government aims to control or contain Covid-19 have been quietly abandoned on the grounds of political expediency bolstered by spurious herd immunity arguments. Disparities in public health policy between England and other parts of the UK have been deliberately exploited to revive forms of English nationalism that have helped shore up support for Johnson and his acolytes within the Conservative Party. We have somehow moved from what might have been a form of science-led public health policy towards a very different kind of social and political configuration led by shifting alliances on the right of British politics.

Urban political ecology: a critical reconfiguration

Progress in Human Geography 46 (1) pp. 21–43

Urbane Politische Ökologie im Rück- und Ausblick

Sub\Urban 9 (3-4) pp. 289–301

Consider the mink

One of the saddest non-human spectacles in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic has been the mass cull of mink on Danish fur farms in the autumn of 2020. The fate of 15 million mink, which were believed to harbour the C5 variant of the virus, illuminates some of the hidden dimensions to the global “zootechnosphere,” to use the historian Chris Otter’s phrase, and the treatment of non-human others.

The images of these huge fur farms – Denmark is world’s foremost producer – remind us that the significance of the post-Fordist economic transition towards more dispersed or flexible forms of production has been over-stated in relation to capitalist agriculture. The use of large-scale mass production remains very significant for the production of food and many other commodities. The fate of these animals highlights the hidden violence towards animals under modernity that is largely occluded from the sphere of consumption and everyday life. The practical problems in disposing of millions of dead mink are reminiscent of the eerie funeral pyres for cattle slaughtered in the UK in response to the foot-and-mouth outbreak of 2001, in another controversial mass killing of otherwise healthy animals. As in the case of the mink, the underlying reasons for this thanato-biopolitical response are rooted in the unprofitability of caring for unsaleable animals or their products. The use of a cull can be conceived as a brutal kind of corporeal devalorization in which these animals become too expensive to keep alive, despite evident public unease and wider political reverberations.

As the philosopher Clare Palmer shows, the question of animal ethics is often framed by specific situations: the treatment of an animal in a zoo, for instance, is likely to be very different to those confined within industrialized facilities. The question of human obligation to protect animals from harm is clearly context specific: it is rare, for example, to observe human intervention to prevent death or suffering of animals “in the wild” but when non-human others fall under our power or control the ethical questions become more complex and more pressing. It is, after all, the violence of human interactions with nature, and with animals in particular, that has provided the multiple “spillover zones” for many of the most dangerous zoonotic threats under modernity.

An Arkansas parable for the Anthropocene

Annals of the American Association of Geographers

Interview with CityLabs India (2021)

Interview with Professor Pratyush Shankar for CityLabs India:

Urban natures in the Anthropocene (2021)

Pre-recorded colloquium for the Rachel Carson Center, Munich