In Great Yarmouth: Provisional Figures (2023) the Portuguese film director Marco Martins provides a devastating portrayal of post-Brexit Britain and the precarious lives of migrant workers. The screenplay draws on the testimony of former workers and is unsparing in its depiction of their humiliating conditions. The focal point of the film is a blood-soaked turkey processing plant where English workers are no longer prepared to do the dirty jobs. In one scene we see newly arrived Portuguese workers having their teeth and hands checked, in another they are huddled in the cold before dawn, waiting for a bus to transport them to the factory. The central character Tânia (played by Beatriz Batarda) is a former worker who has become a kind of gang master overseeing the needs of the migrants. She has been saving money by overcharging them for their dilapidated housing but she is swindled in turn by one of the workers, leaving her life in ruins. The scenes of live turkeys in crates arriving for slaughter are reminiscent of the startling realism in Charles Burnett’s classic depiction of a modern abattoir in Killer of Sheep (1978). The brutal fate of these bedraggled birds, anxiously peering towards the camera, underlines a generalized sense of hopelessness. The only counterpoint to the nihilistic mise-en-scène is a former nature reserve worker, now a virtual outcast, who has befriended Tânia. In a poignant moment he cradles an injured greenfinch and also lets her hold the bird. The films closes with his voiceover, a childhood lullaby “ten for a bird you must not miss,” the double meaning evoking the aim of a hunter’s rifle or a heart that cannot grieve.

Category: reviews

How to blow up a pipeline

The film How to blow up a pipeline (2022), directed by Daniel Goldhaber and inspired by Andreas Malm’s book, is one of the most important independent films of recent years. The plot centres around a meticulously planned operation by eight young environmental activists to blow up an oil pipeline in West Texas (the film was shot in New Mexico). As the film progresses we learn various elements of the activists’ back stories that have drawn them into taking part in a collective form of direct action such as the death of a family member to environmentally induced cancer or a sense of rage over oil extraction in ancestral lands. The film explores the moral dimensions to property destruction with great subtlety: indeed, part of their action involves turning off the flow of oil to prevent a spillage after destroying a section of infrastructure. The riveting screenplay has a real-time intensity that is reminiscent of John Cassavetes. As a cultural artefact in its own right it is film that is absolutely of its time as we enter the 2020s: a decade of deepening global environmental crisis for which our existing conceptual and analytical tools feel increasingly inadequate.

Grenfell

Steve McQueen’s short documentary simply entitled Grenfell is the most poignant artistic response that has yet been created to the fire that swept through the twenty-four storey Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 in which 72 people lost their lives. The film opens with a quasi-bucolic aerial panorama beyond the edge of London accompanied by intense ambient noise. Almost imperceptibly we are drawn very slowly towards the increasing density of metropolitan London: golf courses and gently curving suburban roads gradually give way to more tightly packed residential streets, signs of light industry, and the criss-crossing of roads and railway lines. As the helicopter-eye view moves ever closer to the group of West London hi-rise housing blocks the pale grey inhabited towers mark a striking juxtaposition with the blackened shell of Grenfell. The background noise fades to complete silence as we slowly begin to circle the charred exterior of the building. The blackened walls contrast with heat distorted materials and raw red patches. Rather than an architecture of trauma à la Daniel Liebeskind we are confronted with architecture as trauma. Filmed in December 2017 the winter light accentuates the combination of harsh colours and absence of life. The mood is meditative and shocking. Ever so gradually the camera begins to draw back. The subsonic shell of ambient sound returns as if the clarity of loss is now threatened by a kind of “white noise” in which memory, responsibility, and justice must jostle to be heard.

Sudan Archives

A sudden thunderbolt hit North London on the early evening of Monday 28th November leading to numerous enquiries about an unexplained explosion or even speculation about a meteor strike. What a fitting meteorological phenomenon to mark the arrival of the musician Sudan Archives in London for her show at the Electric Ballroom in Camden. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the violinist and songwriter Sudan Archives has crafted a genre defying body of work over recent years. Her show was marked by a sense of exuberance in its oscillation between searing violin improvisation and dramatic renditions of “Come meh way,” “Iceland Moss,” and other songs. Even if the somewhat muddy sound system could not convey the subtlety of all her works the atmosphere was electric. It is good to know that live music is flourishing once again in the post-Covid city.

Night Moves

The exploration of radical environmentalism in the thriller Night Moves (2014), directed by Kelly Reichardt, is a fascinating study in character development and ethical complexity. The film steadily builds a sense of extreme tension in relation to the planned destruction of a dam that has unintended consequences. Shot over just thirty days in southern Oregon, the sparsely populated landscape provides a poignant backdrop to the inner turmoil of the three main protagonists. A sense of foreboding permeates the film as it drifts inexorably towards its violent denouement.

High Life

The grim possibilities of multi-generational space travel to reach potentially inhabitable reaches of the solar system are explored in Claire Denis’s film High Life (2019) where human “refuse” is propelled into space as part of a system of extra-terrestrial laboratories. The scarred and psychologically damaged human cargo are “recycled” as part of a largely unseen nexus of scientific experimentation. The film presents an unsettling post-human journey in which the limits to humanity become brutally exposed: in one strange sequence the decaying spaceship docks with another experimental space station full of dead and dying dogs. The doomed mission lies trapped in a liminal state between the claustrophobia of confinement and an inky abyss beyond.

Street scenes: Thomas Struth and the distillation of vision

Among the eighteen photographers featured in the recent show Constructing Worlds at the Barbican Centre in London I want to reflect for a moment on the work of the German artist Thomas Struth. Struth forms part of an influential circle of former students of Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Düsseldorf Academy where significant advances were made in the use of large format black and white photographs to record the scale and detail of urban and industrial landscapes.

One of Struth’s photograph stands out for me in particular, entitled Clinton Road, London (1977), which captures a wide-angle view of an empty London street, perhaps on a Sunday morning so as to be as unobtrusive as possible (save for a possible curtain twitch to the left). In a series of photos taken in the late 1970s in several cities—among them Brussels, Cologne, and New York—Struth sought to distil the essence of an entire city into a single image. In the case of London this is no easy task. Nevertheless, this street is instantly recognizable as an example of the type of turn of the century terrace housing that dominates many of London’s newly built suburbs of the late nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries. There is a studied ordinariness to this image that captures something of the enigma of London as a city.

Sometimes it takes an outsider to notice what is taken for granted. Like the Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen achieved, with his marvellous book London: the unique city, first published in 1934, Struth has also managed in the field of photography with his carefully chosen location. That this image is a large format image, with all the skill and technical complexity that that entails, merely adds to its poignancy. And with the use of black-and-white rather than colour, the image seems to be both closer in time and yet simultaneously further away.

Material is it: Burri’s modernity

Alberto Burri is one of the most interesting yet little known twentieth-century artists. Born in Umbria, Italy, in 1915 he became one of the leading exponents of Art Informel in Europe during the 1950s. His experimentations with manufactured or synthetic materials can be read as an exploration of the aesthetic characteristics of industrial modernity and the post-war transformation of Italian landscapes. He was certainly influenced by Umberto Boccioni’s Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture (1912), which exhorted artists to combine as many materials as possible in their work. Burri’s fascination with fire, metal, plastics, sacking, and the colour red in particular, was also a significant influence on Antonioni’s film Red Desert (1964), which explores the industrial landscapes of Ravenna. Burri pushed materials to their limits, examining variations in form and texture under extreme conditions, and produced works that evoke organic elements such as body parts, cracked mud, or even the vastly magnified strange worlds that are revealed under the lens of a microscope.

His recent exhibition at the Estorick, London, is the artist’s first solo show in the UK since 1960s. To encounter many of these works gathered together in one place, and to see their rich colours and intricate surfaces in close proximity, is a powerful experience. The discreetly lit gallery rooms cast their own subtle shadows across the many textures producing yet more variations. Though the almost deserted gallery was very quiet I could sense a kind of aesthetic hum as if these works could instil mysterious synaesthetic effects. It appears that Burri himself, however, was resistant to interpretation, claiming that words are of little use, and that his work speaks for itself. Yet it is difficult to ignore the wider context: his experience as a military field doctor before switching to art may have informed the bloody corporeality of some of his works; his encounters with the semi-arid landscapes of southern Italy or North Africa are strikingly evoked by the parched, cracked and burned spaces of some of his canvases; and above all, his consistent fascination with synthetic materials marks a tactile engagement with the manufactured worlds of modernity in all their strangeness and unpredictability.

Trishna

Michael Winterbottom is an erratic and prolific British film director but Trishna (2011) must surely rank amongst his best works to date. In this striking adaptation of the Thomas Hardy novel, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the setting is transposed from late nineteenth-century rural England to contemporary India. The story moves from the rural poverty of Rajasthan to the bustling hi-rise metropolis of Mumbai and then back to Rajasthan for its tragic denouement. The doomed love affair emerging from a chance encounter between Trishna (played by Freida Pinto) and Jay Singh (played by Riz Ahmed) serves as a poignant metaphor for the devastating effects of gender inequality, poverty, and cultural oppression amid the glitz of Mumbai, luxury hotels and the superficial allure of the tourist gaze. The unhurried cinema verité style lends weight to the unfolding drama. The everyday scenes of agricultural labour and factory work, for example, are reminiscent of the video art of Harun Farocki. A sense of fatalism and dusty monotony is powerfully evoked.

By moving Hardy’s novel to a different setting Winterbottom succeeds in drawing out broader themes concerning the tension between modernity and tradition. The striking cinematography, along with very effective use of music, also poses interesting questions about vantage points for cinematic representation. To use a nineteenth-century British novel as a means to depict contemporary India is fraught with potential difficulties in terms of the blurring of period, place and perspective. What is clear, however, is that Trishna is a far more effective, and in many ways honest, portrayal of contemporary India — albeit from a very specific viewpoint — than other less interesting works that struggle to combine “slumdog” realism with narrative convention.

Barbara

Contemporary cinematic depictions of the DDR have tended towards the ludicrous — Goodbye Lenin (2003) — or the implausible — Das Leben der Anderen (2006). In Christian Petzfold’s Barbara – in competition at the 2012 Berlinale – a very different approach is adopted. In this striking and emotionally intense film, set in the summer of 1980, we follow the travails of a talented young doctor, Barbara (played by Nina Hoss), who has been banished from Berlin to a provincial hospital in a small town near the Baltic coast after asking for an exit visa. A claustrophobic atmosphere of mistrust, spite and state repression is brilliantly evoked, against which Barbara and her colleague Andre (played by Ronald Zehrfeld), also evidently banished to this hospital, gradually get to know each other. This is a subtle and highly accomplished film that elicits superb performances from both Hoss and Zehrfeld. Not wishing to give too much away — I hope very much that this film is widely shown outside Germany — the final denouement of an attempted escape is both riveting and extraordinary.

Inside out: Vermeer, de Hooch and the interior landscape

I set off in the winter gloom yesterday to see a small exhibition of the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer and some his contemporaries at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Given that so few of Vermeer’s paintings still exist it was wonderful to see four in one go alongside a range of lesser known artists such as Gerard ter Borch and Nicolaes Maes, as well as more familiar works by Pieter de Hooch and Jan Steen. The exhibition entitled Vermeer’s women: secrets and silence focuses on the depiction of women in a series of interior settings engaged in various tasks ranging from household chores to more contemplative moments reading, writing or playing music. Many of these paintings — which deploy various strategies in achieving different level of realism — consist of frames within frames: windows, doorframes, picture frames, linked courtyards (as in de Hooch) and other elements that emphasize our immersion in an interior and largely private landscape of domesticity that is dominated by the presence of women.

Seeing these paintings gathered together it is interesting to consider whether Vermeer’s pre-eminence within seventeenth-century Dutch art has been simply a quirk of canon formation or a real reflection of his better work. With the partial exception of de Hooch this exhibition shows that Vermeer was way ahead of his contemporaries. The structure of his compositions is less cluttered and by tending towards abstraction Vermeer paradoxically emphasizes the faithfulness of his works to human perception since our eyes shift their focus within any given frame to emphasize certain elements over others: in this way what we actually see is as much a reflection of our mind as what is actually there before us. In works such as The lacemaker (c. 1670) and The music lesson (c. 1662-3) there is a use of variation in soft and sharp focus to directly emulate and at the same time subtly guide the human eye. His works also lack elements of whimsy or Arcadian motifs lurking in some of his contemporaries: the exterior view in Conelis de Disschop’s rather dreary Girl peeling apples (1667), for example, depicts not a Dutch town but what appears to be some ivy-clad Italianate ruins. Most significant of all, however, is Vermeer’s use of light, which is so effective and so meticulous that it reveals not just the shimmering beauty of everyday objects or the human figure deep in contemplation but also works as a deeper metaphor for human thought and creativity itself.

Maurice Pialat’s realism

The French film director Maurice Pialat (1925-2003) did not make many films but left a distinctive cinematic legacy. We could say that Pialat is a “humanist” film maker in the sense that he explores universal themes such as death, desire and jealousy, yet these are presented through the specific cultural lens of post-war France. Though less well known than his contemporaries such as Eric Rohmer, who also examines intricate aspects to everyday life, Pialat remains one of the most powerful and thought provoking of European film directors.

Pialat achieves a heightened sense of realism by a loose style of direction that allows for improvisation and the incorporation of les choses du moment [fleetings things]. As an actor himself Pialat also deploys the deliberate use of surprise to create provocative situations: his abrupt return as the estranged father in A nos amours [To our romance] (1983), for example, was not revealed to his cast so that they share in our own bewilderment. Another very interesting feature, that is reminiscent of the American film director John Cassavetes, is his focus on “real time” social situations: the intense conversation between mother and adult son after her cancer diagnosis in his study of death, La guele ouverte [The mouth agape] (1974), is marked by a series of silences, glances and inscrutable facial gestures. For Pialat, the presence of impending death serves as a catalyst that exposes the raw fragility of human relationships, provoking outbursts of anger, desire, laughter and despair. In La guele ouverte, the documentary feel to the film, with its unpretentious and fine-grained emphasis on detail, is also enhanced by the presence of several non-professional actors. Above all, Pialat presents us with an emotional realism that few other directors can rival.

Cloud formations: landscape and politics in the art of Gerhard Richter

The German artist Gerhard Richter, who has a major current retrospective passing through London, Berlin and Paris, has been producing some of the most interesting explorations of landscape since the 1960s. Richter provides a subtle counter point to the leaden sweep of European romanticism by reworking a whole range of familiar motifs such as mountains, forests and cloud formations to emphasize their perceptual and intellectual limitations as sources of certainty or truth.

His extensive use of blurring highlights the degree to which we try to read meaning into landscape: the way swirling clouds or the scatter of light across the forest floor can set off any number of possible patterns or permutations. Like the colour play of late nineteenth-century neo-impressionists, and their attempt to convey a higher level of visual realism in nature, we find that Richter is keen to explore the infinite possibilities of human perception. His distrust of ideological metaphysics places him far apart from the neo-romanticist lineage of Heidegger, Beuys and their postmodern progeny.

Working at the interface of painting and photography Richter has created a series of powerful juxtapositions: his aerial rendition of Paris, for example, is suggestive of a bombed out shell, reminiscent of post-war Cologne or Dresden, whilst his blurred Baader-Meinhof series emphasizes our lack of understanding of terrorism and the effects of ideology. His exquisite portrait paintings reference the seventeenth-century realism of Vermeer and his attempt to achieve new levels of technical perfection. In Richter’s hands, the practice of painting forms part of on-going dialogue with other forms of representation that range from the seventeenth-century camera obscura to the advent of digital photography.

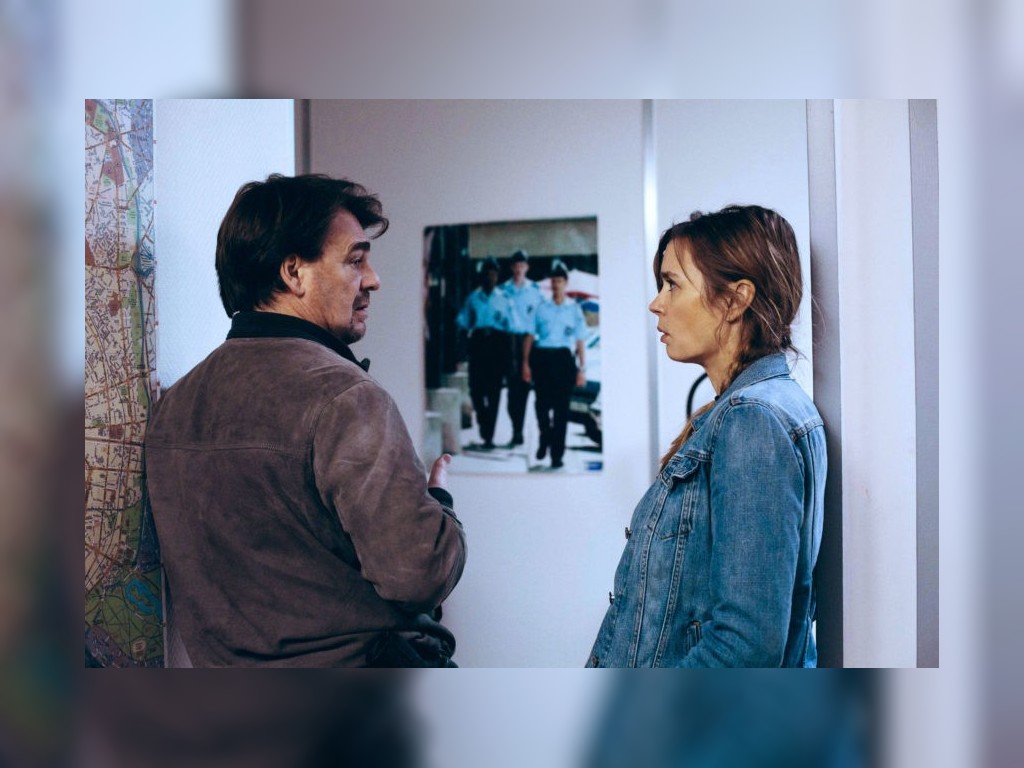

Engrenages [Spiral]

The French TV drama Engrenages — released as Spiral for English-speaking audiences — inhabits a terrain somewhere between the Baltimore depicted in the The Wire and the Copenhagen of Forbrydelsen [The Killing]. Set in contemporary Paris, Engrenages is based around a series of grisly crime investigations that evoke a dark archaeology of the city as a nest of corruption, deceit and violence. The pivotal character is undoubtedly the police captain Laure Berthaud, played superbly by Caroline Proust, who fearlessly pursues her opponents with a combination of recklessness and vulnerability. The “baddies” that we encounter are a truly remarkable menagerie of monsters, ranging from corrupt lawyers to various psychopathic murderers, who at times correspond to various pre-conceived stereotypes ranging from Arab hustlers to eastern European pimps. At a political level, therefore, the drama is not particularly incisive: unlike the multi-layered Baltimore of The Wire we never get a compelling sense of how Paris works as a city. Many of the characters are too one-dimensional for us to invest much emotionally in their respective fates and the lines of sexual and racial difference evoke little more than a claustrophobic ambience of danger and paranoia. Ironically, Engrenages owes too much to second-rate crime dramas and not enough to more experimental TV drama. For a city that is as much shaped by its post-colonial present as its imperial past the Paris of Engrenages seems somewhat limited in its scope.

Let England shake: PJ Harvey at the Royal Albert Hall

Polly Jean Harvey, currently artist-in-residence at the Imperial War Museum, played a sold-out gig last night at London’s Royal Albert Hall. There was an unmistakable buzz about the venue as the cavernous auditorium filled to capacity amid a roar of excited conversation.

And then the lights dimmed and she was there. Dressed in black, and standing to one side of her small backing band, she briskly played the whole of her prize-winning new album. Although the acoustics of the space are famously muddy her searing anti-war lyrics were clearly audible, the words leaping from the shadows, and providing a poignant contrast with more jingoistic connotations of the venue. Though a response to contemporary wars, PJ Harvey’s latest work draws on the elegiac futility of the First World War as a symbol for all wars, and the shattering and splintering of young lives. “Soldiers fell like lumps of meat,” she sings to the incessant rhythm of “The words that maketh murder”. It is not just the mist-shrouded battlefields, swarming with flies, that Harvey evokes, but also the poisoning of England itself:

Let me walk through the stinking alleys

to the music of drunken beatings,

past the Thames River, glistening like gold

PJ Harvey is an uncompromising artist: critically acclaimed yet meeting with only modest commercial success. She exemplifies a paradoxical outcome of the political economy of music marked by a renewed re-orientation towards live performance: since it is increasingly difficult to make money from selling music, or even control the sequence of tracks on an album, the artist must look towards the live performance not just to sustain their living but also as a means to impose their artistic vision: for Harvey to play her new album in its entirety is a real-time artistic statement of how it should be heard. In the encore, however, she delves into her back catalogue, with mesmerizing renditions of “White Chalk” and “Angeline” that send shivers down the spine.

Hævnen

The Danish film Hævnen (2010), also released under the English title of In a Better World, is a real gem. Directed by Susanne Bier, Hævnen, meaning revenge in Danish, is a subtle and powerful exploration of anger, grief and violence.

A bullying incident at school invokes a brutal retaliation that leaves us feeling decidedly uneasy: the bullied boy’s new friend is struggling with grief over his mother’s death which he channels into a ferocious assault on the school bully. We want a decisive retaliation but the incident goes too far. At this point the film bears some initial similarities with David Cronenberg’s A history of violence (2005), but in Hævnen the sense of emotional tension is sustained throughout and there is no descent into cartoon mobsterism.

The bullied boy’s father, played superbly by Mikael Persbrandt, is also caught in an ugly street incident watched by his son and his new friend (and protector). The father is slapped and insulted by an aggressive stranger but does not retaliate. He tries to explain that his passivity is a sign of strength but his son and his friend cannot accept this and secretly plan a revenge attack of their own.

As a parallel narrative, the father of the bullied boy works regularly as a doctor in a refugee camp in war-torn east Africa: a few days later he is faced with the moral dilemma of treating a man who has brutally attacked women in nearby villages. After his treatment, however, the man begins to taunt the doctor over his crimes and in a sudden rage the doctor pushes him to the ground. It is a striking and extraordinary scene that profoundly tests our emotional response to anger.

Using the tranquil Danish countryside as a backcloth Hævnen is a multi-faceted exploration of how anger drives and distorts human relationships. Bier presents a much more effective exploration of violence than Cronenberg because she detects the incipient traces of violence all around: there is a pervasive sense of fury that leaps like sparks between the main protagonists. The eventual denouement, following the boys disastrous attempt to avenge the street incident, is all the more powerful because we have grown to know the complexities of the individual characters and we as an audience have made an emotional investment in the final outcome.

Earth [Zemlya]

At the BFI Southbank today I had the chance to see Alexander Dovzhenko’s rarely shown silent film Earth [Zemlya] accompanied by live piano music. Made in the summer of 1929 in rural Ukraine the film opens with a swirling sea of wheat that is reminiscent of Terrence Malick’s Days of heaven (1978). This is followed by a series of delicate images of human faces, sunflowers and apples. The low position of the camera lends the human faces a “heroic quality” outlined against the vast sky.

The core theme is the coming collectivization of Soviet agriculture centred on the arrival of the first tractor — the “iron horse of Bolshevism” — and the latent tensions between peasants and kulaks. For contemporary Stalinist critics, however, Earth was not considered political enough and Dovzhenko was widely vilified for his lyrical and sensuous vision. By the film’s release in 1930 the brutal aspects to collectivization were becoming increasingly apparent and the idyllic landscapes depicted in Earth were to become spaces of devastation.

In the closing scenes we see apples, melons and pumpkins in the rain. Yelena, the bereaved wife of the young farmer Vassili, has found a new lover. And the poetic qualities of the film leave us to reflect on time, nature and the yearning for a “new life”.

Fish Tank

In Andrea Arnold’s extraordinary film Fish Tank, first released in 2009, we encounter the landscapes of Rainham on the London/Essex border experienced largely through the eyes of fifteen-year old Mia, played to incredible effect by the unknown actor Katie Jarvis, who was apparently spotted by the casting agent on a railway platform. Though Rainham is not quite an explosive banlieue in the French sense it is nonetheless portrayed as a space of intense social and cultural marginality.

In Fish Tank Arnold builds a profoundly claustrophobic mood that is matched by an oppressive “edge” landscape of utilitarian functionality dominated by highways, pylons and superstores. In perhaps the most striking scene, however, Mia, along with her mother, her younger sister, and her mother’s new boyfriend, enter a hidden space of “wild urban nature” where they encounter the beauty of nature, symbolized by the fleeting appearance of a blue damselfly by the edge of a small lake.

Arnold may well be the most exciting contemporary British film director. There is an enigmatic dimension to her work — also reflected in Red Road and the short film WASP — that builds a sense of emotional complexity and unpredictability. Her cinema attains a certain kind of vivid realism that is rooted in an uncompromising corporeality combined with an exploration of the inner foment of her cinematic protagonists.

Is terrain vague a vague concept? Reflections from Brussels

A couple of weeks ago I attended a conference in Brussels and was intrigued by an “empty space” just next where I was staying in the centre of the city. Bordering the busy Avenue de la Toison d’Or is a large plot of land — overlooked by billboards announcing the imminent “city of tomorrow” — that is currently a jumble of rubble and weeds fenced off from the rest of the city. Having climbed through the wire mesh on a bright Sunday morning I wondered whether this might be the kind of space that the Spanish architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales has termed terrain vague.

In an essay published in the collection Anyplace, Solà-Morales sets out his definition of terrain vague in some detail. He begins by locating the concept within the history of urban photography:

“Empty, abandoned space in which a series of occurrences have taken place seems to subjugate the eye of the urban photographer. Such urban space, which I will denote by the French expression terrain vague, assumes the status of fascination, the most solvent sign with which to indicate what cities are and what our experience of them is.”

Having explored the origins of the word vague and its “triple signification” as “wave”, “vacant” and “vague” he then adds:

“Unincorporated margins, interior islands void of activity, oversights, these areas are simply un-inhabited, un-safe, un-productive. In short, they are foreign to the urban system, mentally exterior in the physical interior of the city, its negative image, as much a critique as a possible alternative.”

And then a few paragraphs later the crucial sentence that seems to capture perfectly the essence of this plot of ground in Brussels:

“When architecture and urban design project their desire onto a vacant space, a terrain vague, they seem incapable of doing anything other than introducing violent transformations, changing estrangement into citizenship, and striving at all costs to dissolve the uncontaminated magic of the obsolete in the realism of efficacy.”

The concept of terrain vague seems, however, to be overwhelmingly visual in its scope. It is difficult to connect the essentially aesthetic response of Solà-Morales to a consideration of how such anomalous spaces appear and disappear within the city and how they might connect with or illuminate wider processes of urban transformation. In the case of the Brussels quarter of Ixelles/Elsene this is an area that is undergoing rapid change: a vibrant predominantly Congolese community is being gradually squeezed out, house by house, to enable a new kind of “international city” to be created. In fairness to Solà-Morales his concept is rooted in the history and theory of urban photography but how do images intersect with urban theory? And what can “territorial indications of strangeness” — to use another phrase of Solà-Morales — actually reveal about the urban process? It may be that terrain vague cannot easily be used in isolation and is best considered as one of a number of interesting terms that adds to the lexicon of urban thought. And of course there is a contradiction to my response to Solà-Morales since I am also wandering around the streets of a city I hardly know with a camera in my hand.

La Vallée (Obscured by Clouds)

The British Film Institute recently screened a new print of Barbet Schroeder’s classic depiction of exploration and self discovery set in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. The film La Vallée (1972), also known as Obscured by Clouds, concerns a group of hippies who set out to discover a lost valley. The expression “obscured by clouds” refers to those areas that have never been cartographically surveyed since they are always blanketed in cloud.

Schroeder himself attended the BFI screening and referred to the film as “borderline, fiction, borderline documentary”. For Schroeder, what is interesting is not the final destination — which they never reach — but the journey itself as a symbol of dissolution for 1960s counter culture. He cited TS Eliot: “We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time”. In La Vallée the idealistic travelers become confused and disoriented: some of them imagine that they have found an understanding with nature and pre-modern culture but this proves to be a touristic chimera that provokes dissent within the group.

My interest in this film is not purely coincidental. Whilst studying geography at university I was sitting in a pub — I think it was the Eagle in Cambridge city centre — and a colleague mentioned that there was to be a research expedition to Papua New Guinea but one of the team had to drop out due to ill health. Without a second thought I said I would go. Some ten weeks later I was tramping through cloud forest — a distinctive kind of rain forest to be found at higher altitudes — and I remember the strange stillness of the moss-covered trees. One morning, just after dawn, I emerged from my tent and the cloud had temporarily cleared: there was ridge after ridge of green forest stretching out to the horizon.

The thing that I remember most vividly about Papua New Guinea was not the landscape, however, but the violence. Having stayed a few days in one of the villages some of the women began to tell me how terrible their lives were: the constant threat of domestic violence, the risk of rape while washing clothes by the river, and the perpetual state-of-war between different communities. Having been steeped in neo-Marxian literature at the time I realized that capital can only provide a partial explanation: questions of gender are of parallel if not greater significance. For the final part of my journey I went on alone to visit the Trobriand Islands off the coast of New Guinea, which proved to be a very different world. This was a matrilineal society based largely around farming and fishing. The men often wore hibiscus flowers in their hair and the aura of imminent violence was absent. It seemed clear that human culture could develop in any number of possible directions and that there is nothing innate about gender relations at all.

Cave of forgotten dreams

Werner Herzog’s latest film is a documentary about the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in the Ardèche region of southern France. The cave, first discovered in 1994, contains what are believed to be the oldest human paintings ever found, dating from over 30,000 years ago. The walls of the cave are festooned with intricate depictions of animals that would have roamed the glaciated landscapes of southern Europe at the time including bison, horses, lions, mammoths and rhinoceroses.

The film is visually spectacular, not least through the adoption of 3D technology to enhance the contours of the cave walls. The excellent cinematography enables us to look very closely at the remarkably preserved paintings along with the strange accretions of crystals and other geological features. The overall aesthetic effect is at times, however, rather bombastic or even operatic: Herzog’s own commentary begins to occlude the archaeological insights so that the documentary ends up being more about him than the cave itself.

Herzog’s work is marked by a tendency towards cinematic machismo. In one above-ground scene he mocks the spear-throwing ability of an archeologist that would have been no match for his distant ancestors (we can infer that Herzog rather fancied his chances of survival in the Paleolithic era). His mode of interviewing is marked by the use of leading questions — perhaps to a greater extent here than in his earlier documentaries — as he steers assembled scientists towards more speculative and metaphysical themes. The paintings, intones Herzog, represent nothing less than the origins of the human soul.

The film is also marred by an idiotic postscript featuring albino crocodiles inhabiting a giant greenhouse that uses waste water from a nearby nuclear power plant. With this final lapse into self parody — we also meet some of Herzog’s beloved reptiles in his recent “remake” of Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant — the documentary seems to lose its way and we are left with the director’s rambling insights into the human condition.

Untitled with rain

John Fahey’s instrumental Untitled with Rain, timing in at just under 24 minutes, is a mesmerizing piece. It is included on his final album Red Cross recorded shortly his death in 2001. The sparse instrumentation consists of guitar, bass and organ, accompanied by the sound of rain. Fahey’s plaintive guitar playing builds an introspective mood, at 2’30” the organ sound begins to shimmer and becomes louder, heightening a sense of emotional tension, at 4’36” a voice calls out “Hi there John” and the atmosphere of a small club is invoked on a dark rainy evening. At 6’32” some gentle chimes denote the minimal use of percussion and by 6’52” the music has faded to nothing – we are left with complete silence for nearly 17 minutes. Yet symbolically we are still within Fahey’s musical space just as John Cage brilliantly recast the meaning of silence with his 4’33” in 1952. Fahey’s Untitled with Rain is a meditation on presence and absence. It is an ambient soundscape that draws everything in and then vanishes to leave only our imagination.

The Passenger

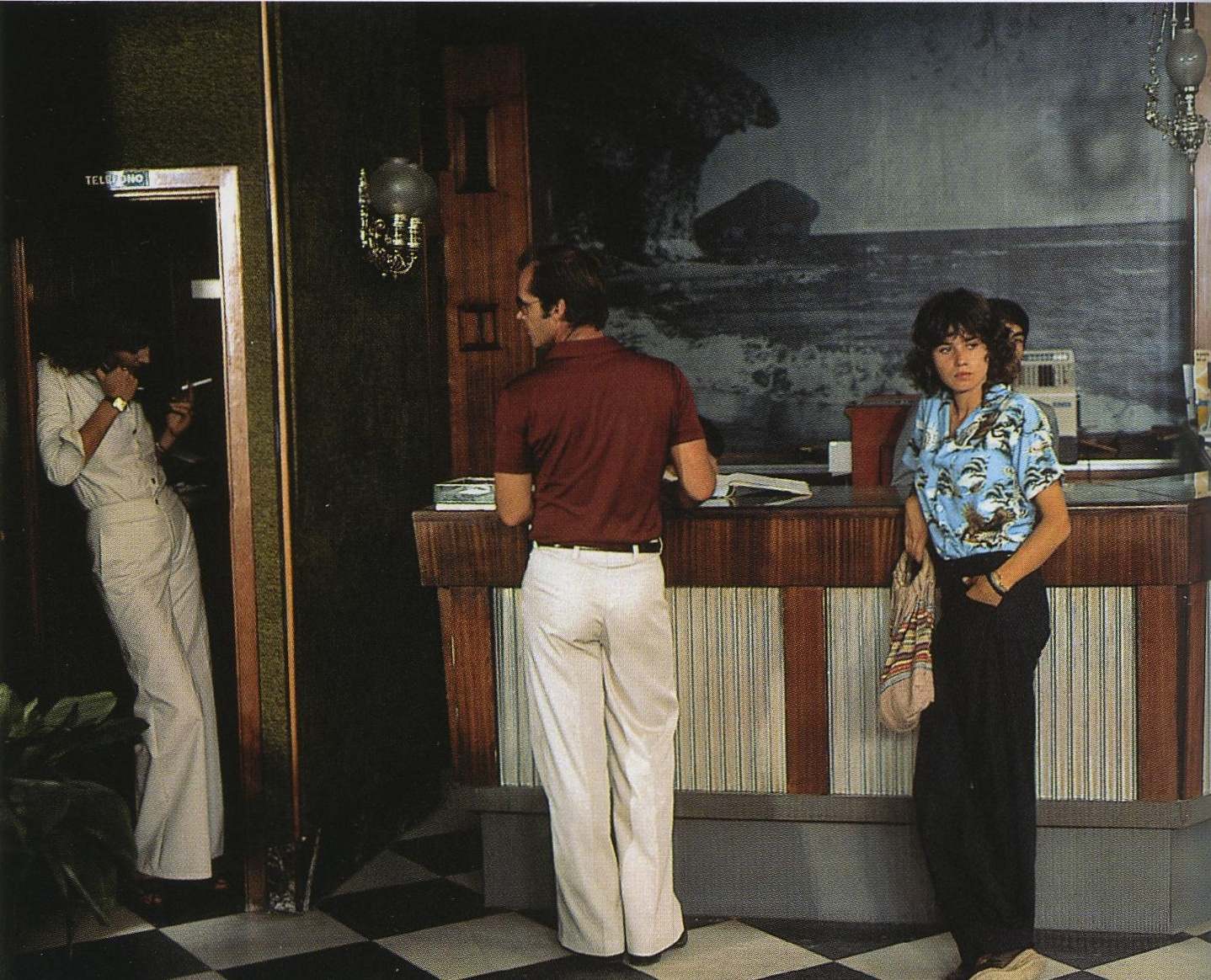

After reading Maria Schneider’s obituary yesterday I decided to watch Michelangelo Antonioni’s film The Passenger (1974), where she appears as a young architecture student who befriends a journalist, David Locke, played by Jack Nicholson, who has exchanged his identity with another man after finding him dead in a small hotel in North Africa. After taking his new identity Locke begins to enter the dead man’s life by keeping various appointments in his diary, including business meetings across Europe. In so doing Locke discovers that the man was in fact an arms dealer and that he has now immersed himself in the politics of a civil war, which he had previously only engaged with as a journalist. By the use of flashbacks, and in one instance a real documentary sequence, the film hovers between past and present, and between different strands of reality.

Although I have seen The Passenger a couple of times before it remains one of the richest and most complex of Antonioni’s movies with fascinating location shots in Chad, Munich, London and Franco era Spain (including sequences in Andalucia and Barcelona). From the opening scenes we find Antonioni’s characteristically sparse and geometric use of landscape, ranging from the dune formations of the Sahara to London’s Brunswick Centre. There is an intricate attention to detail such as the ambient sound of whirring fans, the architectural façades of Antoni Gaudí or swirls of dust in an orange grove, that evoke the fog of his earlier film Red Desert (1964).

Perhaps the most striking sequence is when they leave Barcelona in an open top car, driving at speed into the Catalan countryside. “What are you running away from?,” asks the student. “Turn your back to the front seat,” replies Locke, and we see her delighted expression bathed in the dappled sunshine of the roadside poplar trees as she observes the road receding into the distance.

The Passenger is about identity and the ultimate impossibility of escaping from ourselves. This at times obtuse yet technically brilliant film uses landscape to great effect to evoke a spectrum of emotions from wonder to despair: Antonioni is intrigued by the psychological “effects” of landscape and the possibilities for space to elicit unexpected responses from his cinematic protagonists. The pacing of the film is slow: the tragic denouement, for example, is conveyed by a remarkable seven-minute tracking shot that brings together all of the main characters. Yet the slowness of the film is vital to its effectiveness as an exploration of mood, place and the subtleties of human relationships.

Between science and aesthetics: the ecological art of Ulrike Mohr

On 4 April 2006 the demolition of Berlin’s Palast der Republik was halted for one day. The artist Ulrike Mohr was to be allowed to undertake a systematic botanical survey of the trees and other plants that had colonized the roof since German reunification. This vast public building had fallen into a state of disrepair since the early 1990s and had become a kind of ecological laboratory for the study of urban change. Small fissures in the concrete and bitumen had allowed an accumulation of organic matter, and in addition to the typical adventitious species of plants one might encounter growing out of cracks in roads or pavements there were now well-established trees such as birch, poplar and sallow, indicative of the early stages of a rooftop forest in formation.

Mohr’s investigation of the ecological consequences of urban entropy entitled Restgrün [Remaining green] raises important questions about the intersection between science and aesthetics. The study of abandoned spaces is not just a question of aesthetic curiosity but also holds significant scientific implications: in the case of Restgrün, for example, one of the trees found growing on top of Berlin’s Palast was Populus nigra, which is on the Red List for regionally endangered species.

For the 2002 project Versuchsanordnung Acer Platanoides [Test set-up Acer platanoides] Mohr chose a six-meter-high Spitzahorn, or Norway Maple, Acer platanoides, growing in the Künstlergärten Weimar, and stitched together the tree’s leaves with red thread so that they were unable to fall during the autumn. The entire leaf structure was then carefully removed by crane and put on public display in Mohr’s first solo show at the Kunstverein Hildesheim. With this “ecological interruption” Mohr performed a non-utilitarian intervention in nature: we are invited to reflect on the meaning of nature through its unexpected cultural appropriation so that there is both a temporal and spatial dislocation in a largely unnoticed yet remarkable everyday transformation: the annual shedding of leaves by a maple tree.

This notion of time in nature — referred to in ecological science as “succession” — connects with a fascination with the spontaneous re-arrangement of nature. Mohr plays on the boundary of human intervention in nature in two ways: first, by simply observing nature its meaning and significance change, bringing mundane elements such as a common tree or an assemblage of weeds into a profound form of aesthetic engagement; and second, by simply focusing on one element of nature and performing simple modifications, we contend with the scope and complexity of our relations with nature as an extension of ourselves. In this last sense, Mohr brings her exploration of nature into a historically specific scientific frame: her works connects powerfully with the development of urban ecology in post-war Germany as a form of intricate and passionate engagement with nature in cities. In particular it engages with the diversity of potential biotopes or habitat niches associated with the type of everyday instances of nature that have been largely neglected by mainstream ecological science.

Among the most ambitious of Mohr’s works is the 2003 large-scale tree-planting project 750 Kiefern in militärischer Anordnung/Konversionsgelände Wünsdorf [750 Pines in military formation / Conversion area Wünsdorf ] in which hundreds of pine saplings that had sprouted spontaneously in the parade ground of a former Russian military barracks in Wünsdorf were dug up, measured and replanted. The trees were arranged in five precise formations of 150 trees, with the tallest trees placed at the front of each of the blocks to suggest an ironic confluence of forestry plantations with military discipline. Photographs of the site from above reveal the ambitious scale of the project, and also its spatial accuracy, so that the young trees in combination with their supporting wooden posts resemble a battalion of soldiers standing to attention. This is, above all, a landscape of control: an attempt to regularize nature that connects with the historic purpose of the site as a training ground for military discipline and the exercise of state power. After the completion of the project the site was allowed to revert back to a process of natural succession towards “secondary woodland” so that the work connects both with a sense of ecological time and also historical time since all cultural or institutional forms are temporally limited in their scope.

The tree planting also signals a counterpoint to Joseph Beuys’s mass action entitled 7,000 Eichen [7,000 Oaks], installed between 1982 and 1987 for Documenta 7, where the placing of these trees alongside upright basalt columns was linked with an ecological critique of modernity in the context of pollution-induced Waldsterben [forest death], and also the nascent German green movement with which Beuys was closely involved. What clearly differentiates the work of Mohr from that of Beuys is her rational engagement with urban nature as an arena for cultural discourse rather than a hidden repository for ecological mysticism. It is Mohr’s critical distance from the German romantic tradition that renders her work especially interesting in an international context.

The art of Ulrike Mohr is characterized by an attention to detail: not just the subtle textures of everyday things, but also an attempt to uncover relationships between aesthetics and science, and between past and present. Her interventions break with neo-romanticist associations and are suggestive of a cultural synthesis with nature that is free from the baggage of transcendental meaning. Her interactions with nature and landscape are far removed from the heavy symbolism of some artists (the work of Anselm Kiefer, for example) or the shamanistic utterances of Beuys and his followers. In the work of Mohr we find a subtle irony, that provides new insights not through further layers of mystification, but through a calm insistence on the social production of meaning.

Of time and the city

There is something mysterious about Terence Davies’s Liverpool from the outset: at the heart of this cinematic meditation on the city, released in 2008, lies a tension between urban change as a process that is brutal and unremitting and the persistence of memory as something that is delicate and filamentary. Memories become maps through places to which we can never return in a world that is changing all about us.

In Of time and the city Davies presents us with a wondrously idiosyncratic and elegiac journey that is filled with anger, joy and despair. Davies becomes the “angel of history” hovering over Liverpool, alternately caressing his troubled city or pouring scorn on the forces that have brought the city to its knees. The film is punctuated by quotes from poetry, literature and philosophy that are narrated to us by Davies with a sense of staccato urgency: poignant lines chosen from Chekhov, Engels, Joyce and others inform us that this is a serious film from the outset. This is not a film that panders to an existing audience but one that seeks to create a new one. Davies is not making a pitch to our touristic curiosity nor is he using the city in a narrowly didactic sense. This is a deeply personal mode of documentary film making that is imbued with a profound sense of emotional intimacy.

Like Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel according to St. Matthew [Il Vangelo Secondo Mateo], released to general amazement in 1964, Davies uses music to sublime effect. Both Pasolini and Davies select music that through its apparent incongruity generates a powerful sense of authenticity and immediacy: faces, images and landscapes are dramatically transformed into far more than their mere physical presence as stones, bricks or flesh. In Of time and the city Davies furiously juxtaposes music and place to transcend the petty cruelties of organized religion or the grinding toil of working-class life. Decaying housing estates are set to Bacarisse; cranes and industrial architecture to Mahler.

Davies reserves his real scorn for the British establishment in all their ineptitude and mean-spirited mediocrity. He exposes the flummery and sexual hypocrisy of organized religion with relish. He excoriates the monarchy and other archaic forms of gluttony that feast on the goodwill of ordinary folk. As we see newsreel footage of the royal marriage — “Betty and Phil with a thousand flunkeys” — and the gilded carriage passes through cheering crowds Davies reminds us that “Britain had some of the worst slums in Europe”. His droll disdain for the establishment is also extended to its would-be cultural assassins such as The Beatles who are rendered little more than a ghostly and ironic presence. Just as Joe Strummer rejected “phoney Beatlemania” back in 1977 Davies now derides the “fab four” as looking like “a firm of provincial solicitors” — “yeah, yeah, yeah” indeed.

As for post-war architecture Davies notes with acerbic understatement that “Municipal architecture, dispiriting at the best of times, but when combined with the British genius for creating the dismal, makes for a cityscape that is anything but elysian”. These would-be utopias had by the early 1970s become spaces of decline and emptiness scattered with broken glass and overlooked by boarded-up windows. Instead of utopia we got a city in a state of retraction and disorder. “We hoped for paradise; we got the anus mundi”. These new architectural forms were often poorly constructed and maintained, displaying but a faint echo of their exemplary prototypes in European cities and containing their own versions of built-in senescence to match the social and political neglect of their new occupants.

Liverpool has been the traumatized epicentre of Britain’s full-scale industrial decline since the 1960s with a greater population loss than almost any other British city. Unlike former industrial cities in Europe such as Hamburg or Milan, which have successfully rebuilt themselves, it is apparent that Liverpool’s contemporary renaissance is slender indeed: not a replenished civil society or newfound industrial acumen but a retail desert populated by gaggles of drunken figures tottering around beneath the glare of streetlights and security cameras.

The final tracking shots of gentrified docks and warehouses evoke a sense of placelessness: these waterside developments with their familiar “brandscapes” could be any one of a number re-fashioned industrial waterfronts from Baltimore to Buenos Aires. “As we grow older,” observes Davies, “the world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated…and now I’m an alien in my own land”. We float with Davies across neon-lit landscapes or hover over boutiques and wine bars that were once factories or churches. At the close of the film we encounter Liverpool “gathered in at gloaming”, a myriad of strange illuminations in the failing light. What has Liverpool been? What have we been?

Beautiful and scathing in equal measure Of time and the city must surely rank as one of the best films about a British city that has ever been made. But the film is not simply about Liverpool: it is also a mordant response to the failures and disappointments of post-war Britain and a bittersweet exploration of the delicate connections between memory and place that anchor our sense of individual and collective identity amidst the tumult of historical change.

El sol del membrillo [The quince tree sun]

Víctor Erice’s documentary El sol del membrillo [The quince tree sun] (1992) is a simple idea: we follow the artist Antonio López Garcia’s attempt, during the autumn of 1990, to paint a quince tree in his back garden. The film seems to emerge quietly in real time on a late September morning as we see the artist arranging his canvas and inspecting the tree; the only sounds are largely ambient, the rumble of a train, a radio playing and incidental moments like removing the stopper from a bottle of turpentine. With gentle time-lapse photography we observe the emerging canvas over coming days; preparation, patience and detail are interspersed with reminiscences with an old friend who comes to visit. Together, they marvel at the beauty of the tree: the shape, the colours and the fullness of the fruit. Garcia is consistently perplexed by small variations in sunlight and the fact the tree itself is changing over time: he paints small white markers on the leaves and fruit to trace changes in the shape of the tree and the gradual sinking of the branches under the weight of the ripening fruit. “I follow the tree,” he remarks, but the weather worsens, the sky is overcast and his sense of frustration grows.

It is late October and we see the stairwell in his house illuminated with light, set to the music of Pascal Gaigne — very little incidental music is used in the film but it drifts through specific scenes to mesmerizing effect. Garcia has now abandoned his attempt to paint the tree and switches to a drawing instead which he refers to as “a map of the tree”. He contrasts his approach with other artists who work from pictures or photographs since he wishes to avoid “aesthetic games” and struggle directly with the impossibility of representation. By mid-November Garcia describes the tree as being in “full decadence” and he picks up the first fallen fruit on the ground and smells it; the leaves of the tree are now beginning to yellow with small blotches and imperfections spreading. “It’s over,” he declares, and he collects up his things, leaving the garden strangely empty for the first time.

Garcia now poses for another artist, his wife María Moreno: he lies on a bed observing a cut crystal and falls into a deep sleep disturbed by vivid dreams. We see shots of Madrid at night: flickering television screens and moving traffic are interspersed with a bright moon and drifting clouds revealed in all their detail. He narrates a strange dream where he is standing with many others and sees his quince tree now transposed somewhere else. We see the tree next to a camera, the fallen fruit lying under the glare of a powerful light. “Dark spots slowly cover their skin in the still air…Nobody seems to notice the quinces are rotting under a light…turning into metal and dust”. And then the garden is shown next spring with shrivelled and misshapen fruit lying beneath the tree but new buds becoming visible on the branches.

This is a remarkable film of almost unimaginable subtlety that emerges from an intense encounter between an artist and his struggle to convey what lies in front of him. In the end it is time and light that defeat him: the growing tree is itself impossible to capture effectively and every small play of light continually transforms the appearance of the tree. Of course this is not a documentary in the conventional sense but something far more interesting: an exploration of the intersection between an outer world of beauty and decay and an inner world of dreams and imagination.

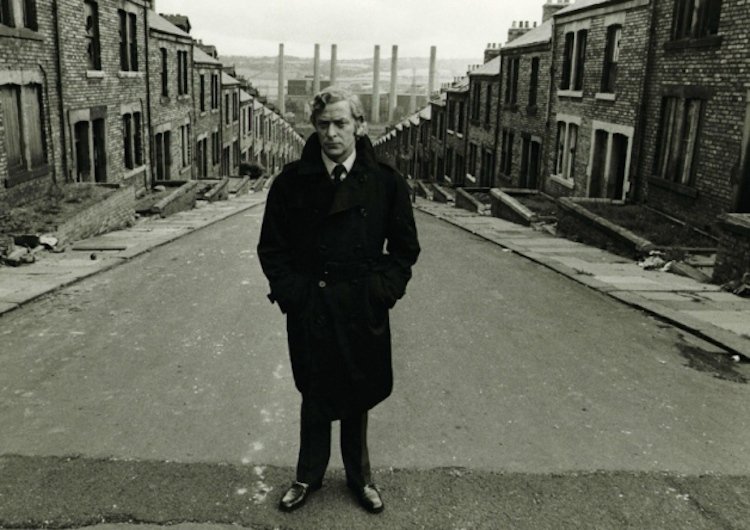

Get Carter

Traveling from London to Newcastle by train the other day I decided to watch Get Carter where a London villain called Jack Carter, played by Michael Caine, goes in search of the truth about his brother’s death. Directed by Mike Hodges, and released in 1971, this impressive British gangster film has a hard-edged realism, laced with wry dialogue, not unlike John Boorman’s depiction of rage in Point Blank (1967) or Stephen Soderbergh’s impressive “fish out of water” drama The Limey (1999). Whilst Point Blank and The Limey are both set in the shadows of Los Angeles, Get Carter takes place in the industrial city of Newcastle in north-east England. In the striking title sequence, set to Roy Budd’s soundtrack, the three-hour train journey is compressed into three minutes as we pass through a succession of different landscapes in the gathering darkness. Newcastle is portrayed as a city where crime syndicates, opportunist urban developers and “new industries” of gambling and pornography permeate society like hyphal threads emerging out of the poverty and industrial decline. “It’s all a question of design,” notes an architect discussing a proposed restaurant at the top of the Trinity Centre Multi-Storey Car Park (designed by brutalist architect Rodney Gordon and demolished in 2010). In Get Carter we find two bleak worlds in uneasy juxtaposition: a decaying working-class city and a “new world” of concrete and corruption. At one level the film serves as a mordant critique of post-war optimism but even more striking after forty years (the film was made on location in 1970) is the oppressive sexual politics exemplified by Carter’s killing of two women: one “by mistake” locked in the boot of a sinking car and the other to frame the man who killed his brother. The film’s denouement takes place near Blackhall Colliery where spoil is tipped directly into the North Sea and our smug anti-hero is gunned down by a cliff top sniper. Get Carter remains a major milestone in British cinema and a brutal antidote to romanticized visions of the early 1970s. With its uncompromising screenplay and stark cinematography it remains one of the most important films in its genre.