In Great Yarmouth: Provisional Figures (2023) the Portuguese film director Marco Martins provides a devastating portrayal of post-Brexit Britain and the precarious lives of migrant workers. The screenplay draws on the testimony of former workers and is unsparing in its depiction of their humiliating conditions. The focal point of the film is a blood-soaked turkey processing plant where English workers are no longer prepared to do the dirty jobs. In one scene we see newly arrived Portuguese workers having their teeth and hands checked, in another they are huddled in the cold before dawn, waiting for a bus to transport them to the factory. The central character Tânia (played by Beatriz Batarda) is a former worker who has become a kind of gang master overseeing the needs of the migrants. She has been saving money by overcharging them for their dilapidated housing but she is swindled in turn by one of the workers, leaving her life in ruins. The scenes of live turkeys in crates arriving for slaughter are reminiscent of the startling realism in Charles Burnett’s classic depiction of a modern abattoir in Killer of Sheep (1978). The brutal fate of these bedraggled birds, anxiously peering towards the camera, underlines a generalized sense of hopelessness. The only counterpoint to the nihilistic mise-en-scène is a former nature reserve worker, now a virtual outcast, who has befriended Tânia. In a poignant moment he cradles an injured greenfinch and also lets her hold the bird. The films closes with his voiceover, a childhood lullaby “ten for a bird you must not miss,” the double meaning evoking the aim of a hunter’s rifle or a heart that cannot grieve.

Category: politics

How to blow up a pipeline

The film How to blow up a pipeline (2022), directed by Daniel Goldhaber and inspired by Andreas Malm’s book, is one of the most important independent films of recent years. The plot centres around a meticulously planned operation by eight young environmental activists to blow up an oil pipeline in West Texas (the film was shot in New Mexico). As the film progresses we learn various elements of the activists’ back stories that have drawn them into taking part in a collective form of direct action such as the death of a family member to environmentally induced cancer or a sense of rage over oil extraction in ancestral lands. The film explores the moral dimensions to property destruction with great subtlety: indeed, part of their action involves turning off the flow of oil to prevent a spillage after destroying a section of infrastructure. The riveting screenplay has a real-time intensity that is reminiscent of John Cassavetes. As a cultural artefact in its own right it is film that is absolutely of its time as we enter the 2020s: a decade of deepening global environmental crisis for which our existing conceptual and analytical tools feel increasingly inadequate.

Grenfell

Steve McQueen’s short documentary simply entitled Grenfell is the most poignant artistic response that has yet been created to the fire that swept through the twenty-four storey Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 in which 72 people lost their lives. The film opens with a quasi-bucolic aerial panorama beyond the edge of London accompanied by intense ambient noise. Almost imperceptibly we are drawn very slowly towards the increasing density of metropolitan London: golf courses and gently curving suburban roads gradually give way to more tightly packed residential streets, signs of light industry, and the criss-crossing of roads and railway lines. As the helicopter-eye view moves ever closer to the group of West London hi-rise housing blocks the pale grey inhabited towers mark a striking juxtaposition with the blackened shell of Grenfell. The background noise fades to complete silence as we slowly begin to circle the charred exterior of the building. The blackened walls contrast with heat distorted materials and raw red patches. Rather than an architecture of trauma à la Daniel Liebeskind we are confronted with architecture as trauma. Filmed in December 2017 the winter light accentuates the combination of harsh colours and absence of life. The mood is meditative and shocking. Ever so gradually the camera begins to draw back. The subsonic shell of ambient sound returns as if the clarity of loss is now threatened by a kind of “white noise” in which memory, responsibility, and justice must jostle to be heard.

Political opportunism as hyper-parasitism

The UK is entering what may be the final act of an extended political farce that has been underway since the appointment of the disastrous David (“I’m giving up my time to govern”) Cameron in 2010. The appointment of Liz Truss as the fourth Conservative prime minister in a row after the departure of Boris Johnson brings a new level of self-serving mediocrity to British politics. Johnson, a populist opportunist, manipulated anti-European sentiment during the unnecessary EU referendum of 2016, in order to destroy the premiership of his Etonian rival, David Cameron. Johnson then worked assiduously to undermine Cameron’s hapless successor, Theresa (“breakfast means breakfast”) May. Now Johnson in his turn has been ousted in a further intensification of Tory in-fighting, the ageing membership having been lured towards the apparition of a Thatcher lookalike as his successor. No matter that Johnson has been replaced by another political opportunist, who campaigned to remain in the EU, but has successfully persuaded the increasingly right-wing membership of the Conservative party that she alone can carry the Brexit revolution forward. Of course, Brexit is not a political destination but a process, an ideological shark that must keep moving to stay alive as Fintan O’Toole and other commentators have pointed out. Although Johnson and Truss both claim that Brexit has been “done” it remains a poisonous mist that continues to infect all around it, damaging agriculture, manufacturing industry, trade, universities, and so on. In inheriting Johnson’s parliamentary majority Truss becomes a political hyper-opportunist feeding off the political capital of her predecessor. We should note that the phenomenon of hyper-parasitism in nature can takes complex ecological forms, with some plant galls displaying at least five levels of parasitism. Similarly, the emergence of political hyper-opportunism contains many layers of intrigue, and could be likened to a kind of political gall — shall we call it Brexit — since the definition of a gall is an “abnormal outgrowth” which can happen from time to time even in democracies.

Ukraine

On 3 March 2022 the Channel 4 News chief correspondent Alex Thomson, reporting from Moscow, made an astute observation about the Russian media landscape that “truth is not a concept, it’s a commodity”. Indeed, the attempt to control information through webs of power and patronage has been a hallmark of the Putin regime since its inception over twenty years ago. The invasion of Ukraine has been based on an attempt to alter history through the manipulation of truth. In this sense I follow the historian Richard Evans’s insistence that a relativist view of the past is dangerous and serves as a breeding ground for ethno-nationalist mobilization. Indeed, the Russian state’s attempt to manipulate global public opinion has been underway for many years, culminating in spectacular successes such as Brexit, the 2016 US Presidential elections, and support for (and from) a motley cast of politicians in France, Germany, Italy, the UK, and elsewhere. It is telling that Volodymyr Zelinskiy, when becoming president of Ukraine, did not request that pictures of himself be put up on the walls of government offices. Instead, he encouraged staff to display photos of their families (presumably including pets). It remains to be seen if the outcome of this terrible conflict will reset global politics towards democracy and away from the realm of violent autocrats and the wilful twisting of history in the geopolitical arena.

The politics of masks

Over recent months I have been working in Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich. Passengers on public transport systems are required to wear masks in order to protect themselves and others from infection with the Covid-19 virus. Not just any mask but a medical standard FFP2 design should be worn (see my photo from the Berlin U-Bahn). I have very rarely seen any passengers without masks apart from an occasional nose on display or the odd maskless mobile phone user (much to the irritation of other travellers).

In Germany the Covid-19 pandemic has focused attention on the need for competent science-led public policy marked by ambitious forms of large-scale governmental intervention to protect both public health and the economy. It is arguable that a political swerve towards calm deliberation and rational decision making may even have contributed towards the surprise outcome of the German federal elections last September when Angela Merkel was suceeded by Olaf Scholz as chancellor. More broadly, critical scholars such as Andreas Malm have asked whether the same level of seriousness in policy making might be applied to other threats such as climate change.

Whenever I return to London, however, I am shocked by the lack of compliance with public health measures. Although mask wearing remains compulsory on London’s public transport system perhaps only half of the passengers make any effort to comply. In the UK it appears that public health messaging has been steadily disintegrating for months, driven in part by the steady stream of revelations of rule breaking by law makers. In the place of clarity and cooperation a sense of confusion and cynicism has taken hold. It is worth recalling that some of the highest death rates from Covid-19 in the UK by occupation have been experienced by public transport workers and other front line staff who deliver essential services. To wear a mask is an act of solidarity with vulnerable workers as well as other passengers. The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has recently reiterated the requirement for people to wear masks on public transport but the police claim that they lack the resources to enforce these public health measures. Earlier government aims to control or contain Covid-19 have been quietly abandoned on the grounds of political expediency bolstered by spurious herd immunity arguments. Disparities in public health policy between England and other parts of the UK have been deliberately exploited to revive forms of English nationalism that have helped shore up support for Johnson and his acolytes within the Conservative Party. We have somehow moved from what might have been a form of science-led public health policy towards a very different kind of social and political configuration led by shifting alliances on the right of British politics.

Consider the mink

One of the saddest non-human spectacles in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic has been the mass cull of mink on Danish fur farms in the autumn of 2020. The fate of 15 million mink, which were believed to harbour the C5 variant of the virus, illuminates some of the hidden dimensions to the global “zootechnosphere,” to use the historian Chris Otter’s phrase, and the treatment of non-human others.

The images of these huge fur farms – Denmark is world’s foremost producer – remind us that the significance of the post-Fordist economic transition towards more dispersed or flexible forms of production has been over-stated in relation to capitalist agriculture. The use of large-scale mass production remains very significant for the production of food and many other commodities. The fate of these animals highlights the hidden violence towards animals under modernity that is largely occluded from the sphere of consumption and everyday life. The practical problems in disposing of millions of dead mink are reminiscent of the eerie funeral pyres for cattle slaughtered in the UK in response to the foot-and-mouth outbreak of 2001, in another controversial mass killing of otherwise healthy animals. As in the case of the mink, the underlying reasons for this thanato-biopolitical response are rooted in the unprofitability of caring for unsaleable animals or their products. The use of a cull can be conceived as a brutal kind of corporeal devalorization in which these animals become too expensive to keep alive, despite evident public unease and wider political reverberations.

As the philosopher Clare Palmer shows, the question of animal ethics is often framed by specific situations: the treatment of an animal in a zoo, for instance, is likely to be very different to those confined within industrialized facilities. The question of human obligation to protect animals from harm is clearly context specific: it is rare, for example, to observe human intervention to prevent death or suffering of animals “in the wild” but when non-human others fall under our power or control the ethical questions become more complex and more pressing. It is, after all, the violence of human interactions with nature, and with animals in particular, that has provided the multiple “spillover zones” for many of the most dangerous zoonotic threats under modernity.

Covid-19

I was wrong about the Covid-19 virus. On Friday 6 March I met with my students in Cambridge to reassure them that I had every intention of taking them to Berlin for their overseas field class: at that time there were just 8 recorded cases of the coronavirus in Berlin and there seemed little reason to simply cancel the planned trip. Just 24 hours later I had changed my mind. The latest figures from the Robert Koch Institute indicate over 2,000 cases of the virus in Berlin (with over 53,000 cases across Germany as a whole). All of the cafes, museums, and restaurants that we would have visited are closed. As a group of 25 people all of our planned field excursions to parks and nature reserves would have been illegal.

As I write this blog I am sitting at home in Stoke Newington in North London. Under placid blue skies there is an apprehensive atmosphere. Many people wear improvised face masks. Some strangers swerve to avoid each other in the street whilst others walk towards you out of defiance towards new rules on social distancing. The few shops still trading have long and anxious queues snaking into side streets. The other day an army truck trundled down Church Street as if a distant coup was underway but not yet announced to the wider population. Strange notices appear such as anti-jogging signs in the local park. Accumulations of refuse suggest that public services are beginning to fray under the pressure. At night the city is quieter than I have ever known—the silence is broken only by the sound of foxes and distant ambulance sirens.

The coronavirus pandemic is already revealing stark differences in the public health preparedness of different nations. The contrast between the UK and Germany is striking: whilst senior members of the UK government fall sick after failing to follow their own half-baked advice it is already apparent that mass testing in Germany, combined with a better prepared health care system, is saving many lives.

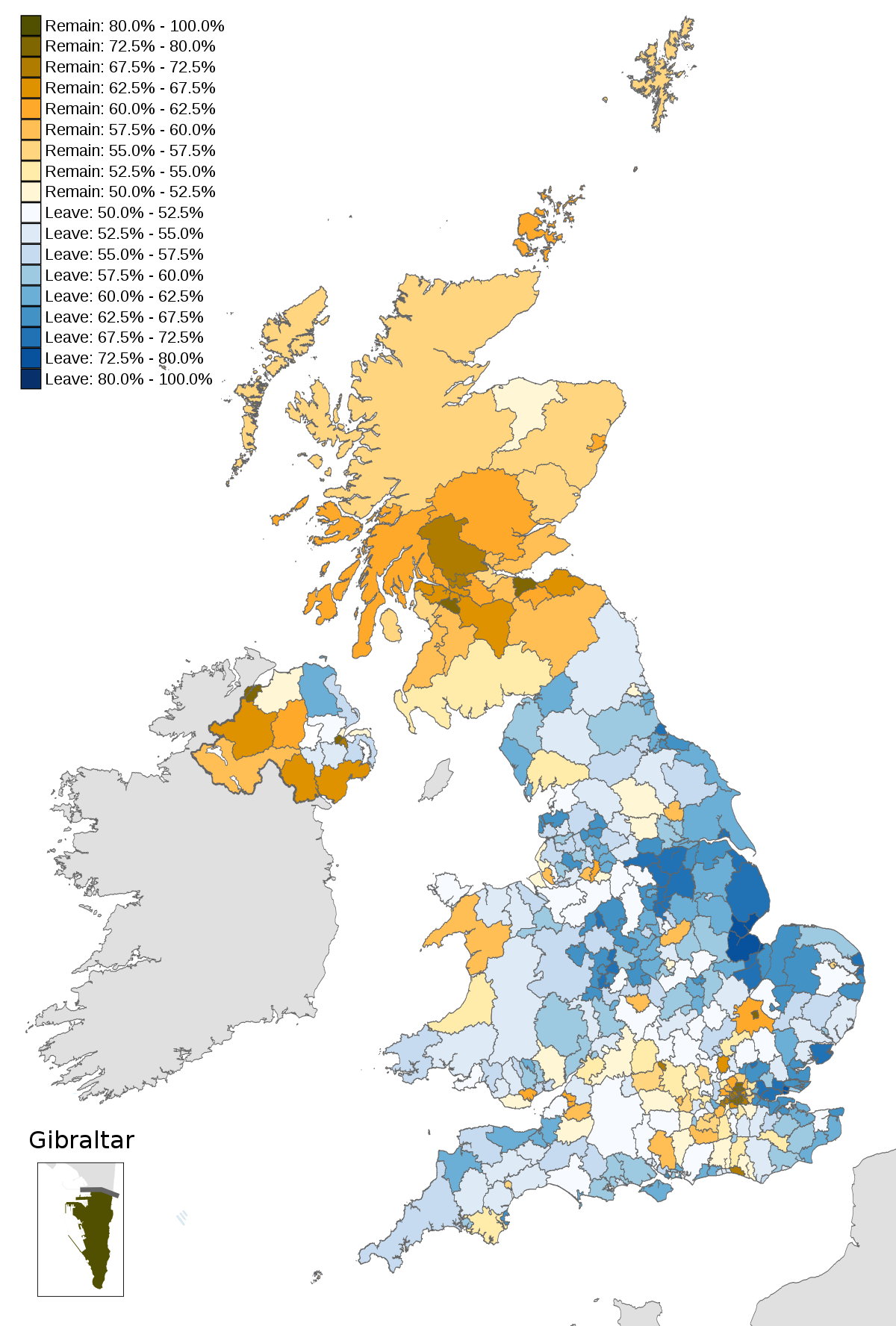

Landscape as political transect

Tower Hamlets (32.5 % Leave 67.5 % Remain)

It is the afternoon of Saturday 25th June and my train draws out of London’s Liverpool Street Station amid a thunderstorm, heading east for Ipswich and Norwich. It is a grubby poorly upholstered train with many empty first class carriages whilst the rest of us are crammed into the other half of the train.

As the train leaves the station I can see a familiar mix of Victorian terraces interspersed with post-war social housing.

Newham (47.2 % Leave 52.8 % Remain)

The Olympic Park, Westfield shopping centre, and high-rise student accommodation.

Cranes, tents, and half-finished buildings in the rain.

Cemetery, pylons, overpass.

Car parks, transport depots, inter-war retail units.

Barking and Dagenham (62.4 % Leave 37.6 % Remain)

Petrol stations, big box Wickes store.

The train slows slightly but does not stop at Chadwell Heath station.

Semi-suburbia and standardized poor quality new build housing.

Havering (69.7 % Leave 30.3 % Remain)

Sports playing fields and multiplex cinema.

We pass through Romford and Gidea Park stations.

Pylons, undulating suburbia, copses.

We are now leaving the administrative boundary of London and entering Essex.

Brentwood (59.2 % Leave 40.8 % Remain)

Sewage works

We pass over the M25 orbital

Splash of green graffiti

Pipe sections by the railway tracks

Heaps of gravel, greenhouses.

Fields fringed with white flowering umbellifers.

Bird on a wire.

Isolated homestead near the tracks.

Muddy brook and country lane.

The white of willow leaves flashing in the sunshine against a dark grey thundery sky.

Chelmsford (52.8 % Leave 47.2 % Remain)

We draw into Chelmsford station, the tracks lined with buddleia, elder, and sycamore.

Political vandals

Last Sunday I followed the lead of Unison’s Dave Prentis and reported Nigel Farage to the police for inciting racial hatred: his now notorious poster depicting refugees seeking a safe haven from war and violence marks a debasement of our political culture that cannot go unchallenged. Given the murder of the Labour MP Jo Cox, and rising levels of racism and xenophobia in the UK not seen since the 1970s, the task of defending society from the politics of hate is a responsibility for every citizen.

When the UK Prime Minister David Cameron foolishly called for a referendum on UK membership of the European Union he set in train a process that has yet to be fully played out regardless of the final outcome on 23 June. At one level we have the spectacle of a Conservative leadership campaign in which political recklessness has been re-fashioned as an absurd bid for English independence that further divides the different nations, regions, and communities of the UK. And standing behind the right-wing populist Boris Johnson is his new aide-de-camp Michael Gove, a curious ideological zealot, still smarting from being sacked by Cameron as Secretary of State for Education. The simmering internal disputes over Europe within the Conservative Party have been re-energized by a cocktail of bitterness and political ambition.

Among the glaring features of this referendum, illustrated yet again by the final debate at Wembley last night, is a pervasive hostility towards “experts” and rational argument. Millions of voters are convinced that the decline of manufacturing industry, falling living standards, and underinvestment in public services is the fault of the European Union and not successive UK governments. The longstanding lack of investment in education, skills, innovation, infrastructure, and all the other ingredients of economic success has scarcely been addressed.

If there was ever an illustration of why a referendum is a crude and dangerous political tool this Thursday’s polarized and unnecessary choice shows why. The EU is not perfect but to leave would be an act of political vandalism based on a misreading of history and a retreat from reality.

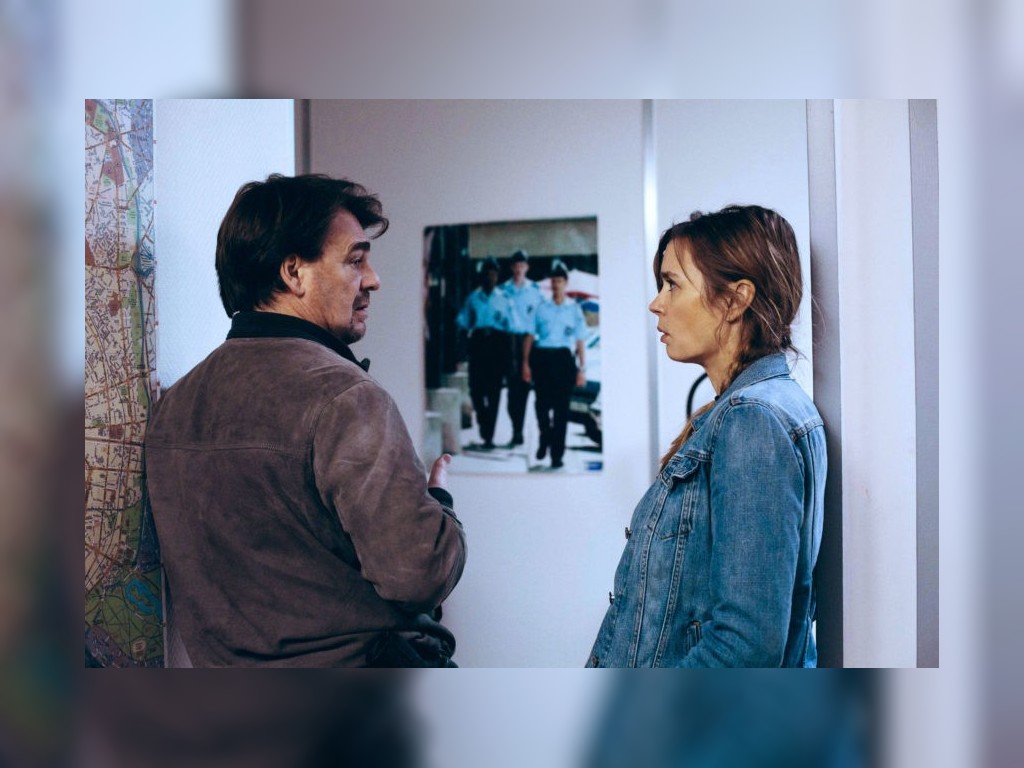

Engrenages [Spiral]

The French TV drama Engrenages — released as Spiral for English-speaking audiences — inhabits a terrain somewhere between the Baltimore depicted in the The Wire and the Copenhagen of Forbrydelsen [The Killing]. Set in contemporary Paris, Engrenages is based around a series of grisly crime investigations that evoke a dark archaeology of the city as a nest of corruption, deceit and violence. The pivotal character is undoubtedly the police captain Laure Berthaud, played superbly by Caroline Proust, who fearlessly pursues her opponents with a combination of recklessness and vulnerability. The “baddies” that we encounter are a truly remarkable menagerie of monsters, ranging from corrupt lawyers to various psychopathic murderers, who at times correspond to various pre-conceived stereotypes ranging from Arab hustlers to eastern European pimps. At a political level, therefore, the drama is not particularly incisive: unlike the multi-layered Baltimore of The Wire we never get a compelling sense of how Paris works as a city. Many of the characters are too one-dimensional for us to invest much emotionally in their respective fates and the lines of sexual and racial difference evoke little more than a claustrophobic ambience of danger and paranoia. Ironically, Engrenages owes too much to second-rate crime dramas and not enough to more experimental TV drama. For a city that is as much shaped by its post-colonial present as its imperial past the Paris of Engrenages seems somewhat limited in its scope.

Cosmopolitan urbanism

Out of curiosity today I checked the etymology of the word “cosmopolitan” and found that it is of seventeenth-century French origin, derived from the Greek word kosmos meaning “world” and polites meaning “citizen”. The word “cosmopolis”, which combines kosmos with polis (the Greek work for city), appears to have first been used in the nineteenth century. So the ideas of world, citizen and city come together through these words and appear to offer an alternative set of ideas to that of an urbanism determined by boundaries, distinctions and exclusions. An enlightened conception of urban citizenship can be conceived as a form of belonging or identification that lies in contradistinction to more narrowly defined notions of ethnic, religious or nationalist affiliation. But who are cities for? Has the progressive promise of the “open city” been captured by transnational elites? Can a liberal city also be a just city in both social and economic terms? A cocktail in a swanky neon-lit bar in downtown Bombay/Mumbai can cost more than the debt that may drive a farmer on the urban fringe to suicide.

The historian Mark Mazower argues that the rise of ethnically defined nation states in the twentieth century, combined with the rise of European fascism, led to the brutal reorganization of previously mixed cities such as Salonica (now Thessaloniki) in Greece. One of the calamitous side effects of Western intervention in Iraq was the destabilization of the mixed character of Baghdad and other cities as new forms of religiosity were unleashed.In Nigeria, for example, there are latent tensions between “generous urbanism”, and the absorption of economic migrants and refugees from elsewhere in Nigeria and West Africa, and underlying ethnic or religious tensions that can easily be exploited. It is striking, however, that in spite of everything, cities remain relatively safe havens from poverty or violence in comparison with their rural hinterlands. Yet under such intense and uncertain conditions, especially in the global South, it remains to be seen whether cosmopolitan urbanism can vie successfully with its intolerant alternatives.Just as cities can also serve as the fulcrum for progressive change they can also serve as citadels of injustice and repression.

Mark Mazower, Salonica. City of Ghosts. Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 (Harper Collins, London, 2004).

Britain on the edge of Europe

Last night the British Prime Minister David Cameron held a celebratory dinner party with right-wing MPs after he used his veto against closer European political cooperation to stabilize the euro which has left Britain more isolated within Europe than at any time in the post-war era. It seems that the upsurge of “Europhobia” fostered by the current government and their media allies has led to a situation where foreign policy is being driven by a few dozen MPs agitating to take Britain out of the European Union along with the lobbying of the financial services sector to prevent the possibility of tighter regulation or the imposition of a transaction tax. Meanwhile, pro-European voices across Britain have been muted and scattered as the longer-term implications of this debacle have yet to be widely recognized. For many in the Conservative Party these events mark the first steps towards a national referendum and the longed for exit from the EU altogether. Isolationist fantasies are gathering momentum as if Britain might be transformed into a larger version of Switzerland.

Britain’s antipathy towards Europe can be read as a kind of neo-colonial fantasy of imagined grandeur: it is interesting to contrast Ireland’s embrace of Europe with that of the UK. Indeed, an independent Scotland, as Alex Salmond points out, would seek closer ties with Europe. Although Cameron’s move appears superficially to safeguard the financial services sector of the UK economy the rationale for London’s economic role within Europe looks set to change as the relative importance of Frankfurt, Paris and other cites begins to grow. The apparent strength of Britain’s separate currency is built on shaky foundations and as the strengthened eurozone pulls away in coming years the economic and political marginalization of the UK looks set to intensify. My political antennae tell me that the eurozone will not break up: one or two countries may partially or even completely default but the overall project has too much political capital invested in it to fail. More broadly, however, we need to rebuild political legitimacy for a progressive European project that can demonstrate real benefits for its people. The underlying tensions between technocratic austerity and neo-Keynesian strategies for growth have not been resolved.

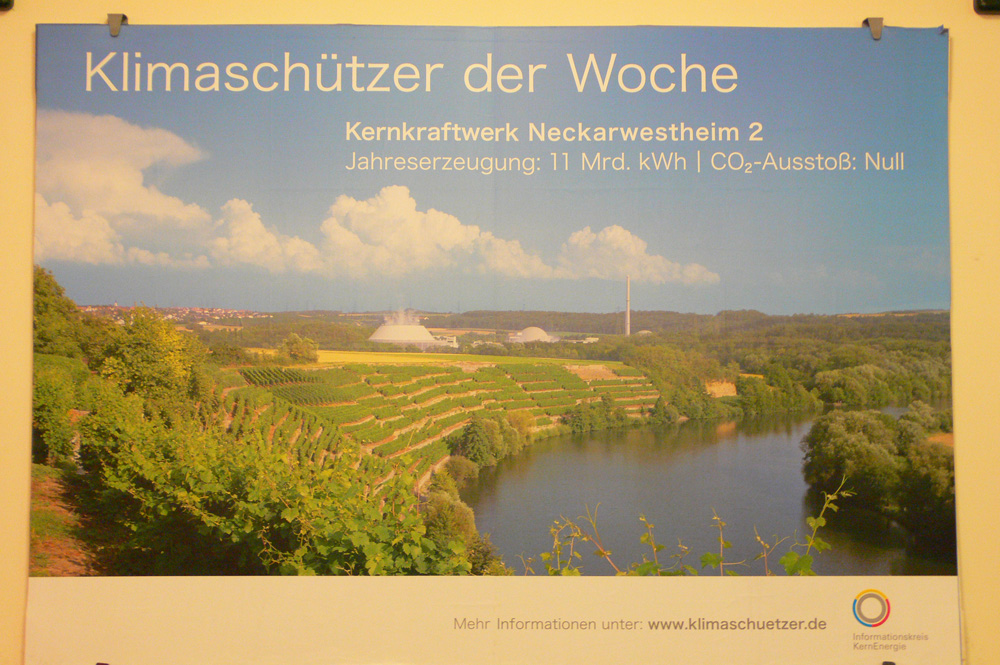

Nuclear power no thanks!

One of the first political issues I engaged with as a teenager was the debate over nuclear power: I decided against and have stuck to my position ever since. In the wake of the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 there was an extended interregnum in which no new plants were commissioned in Europe or North America: ostensibly on the grounds of cost — there was no profit to be made in nuclear power — but also because of continuing public unease and political opposition. The Chernobyl disaster of 1986 simply reinforced this sense of nuclear power as an anomalous and dangerous source of energy with cost, geo-political and environmental implications at every stage from uranium mining and enrichment to eventual de-commissioning and waste storage. Some of the engineering companies engaged in the building and operation of nuclear power plants began to concentrate on less contentious yet still controversial technologies such as waste incineration plants and other capital-intensive projects. It seemed that the nuclear option was in irrevocable decline.

With evidence of accelerated global warming, however, the nuclear industry have seized their chance over the last ten years, with intensive lobbying of governments to underwrite a new phase of expansion. Even high-profile environmental journalists such as George Monbiot appear to have swung behind nuclear power as the only feasible alternative to our continuing dependence on coal, oil and gas. I don’t accept the inevitability of the nuclear path for four reasons: firstly, the unfolding Fukushima disaster in Japan shows that nuclear power remains highly risky even in countries with sophisticated access to technological and regulatory expertise; secondly, as a source of electricity nuclear power only meets one aspect of our energy needs through an apparent “technological fix” that does not address the necessity for far greater emphasis on energy conservation and efficiency; thirdly, the potential contribution of renewable energy sources has been widely stymied; and fourthly, a renewed “blind impetus” towards a nuclear future marks a pathway towards increasingly centralized, undemocratic and unaccountable societies, based ever more around paranoid discourses of “security” rather than environmental protection and social justice. It will be interesting to see whether the regional elections taking place today in the German state of Baden-Württemberg usher in a red-green coalition ready to pursue a different kind of technological future.

Bremen’s elephant

Near the centre of the northern German city of Bremen is a large elephant made of bricks. This imposing ten-metre high structure — designed by Fritz Behn — was completed in 1931 as a monument to the German colonies which then included Cameroon, Togo, Deutsch-Ostafrika [Tanzania], Deutsch-Südwestafrika [Namibia] and several islands. For decades the “Reichskolonialehrendenkmal” stood as a powerful symbol of German colonial ambition that spanned both the Nazi era and the post-war period of reconstruction: an aesthetic continuity that stands in sharp contrast to the hurried erasure of the DDR.

In 1988, however, a metal sign was created next to the elephant by the youth wing of the Bremen metal workers union in support of the Anti-Apartheid movement. In 1990, with the celebration of Namibian independence from South Africa, the elephant itself was re-dedicated as the “Bremen anti colonial monument” thereby attempting to invert its historical meaning yet retaining the original design. And in 2009 a new monument was created next to the elephant to the victims of German genocide: between 1904 and 1908 over 70,00 of the Ovaherero, Nama and Damara peoples of Namibia were murdered followed by an intensified phase of racial segregation that pre-figured the development of Apartheid in South Africa. In contrast to the elephant the genocide memorial adopts a more abstract design reminiscent of land art or street installations: a horizontal array of simple elements such as rocks and stones in the place of vertical bombast.

This assemblage of memorials and plaques reveals that the German colonial presence in Africa was not a minor element in European history: we now know that many of the perpetrators of early twentieth-century violence in Namibia and elsewhere would go on to play a significant role in Nazi expansionism in Europe. In the place of the Herero were the Slavs and others to the east, where an envisioned settler landscape bore parallels with European sequestration of fertile lands in Africa. What is especially interesting about Bremen’s elephant is that it poses the possibility for changing the meaning of public monuments: it allows remnants of the past to become incorporated into new understandings of history. How many other elephants remain unnoticed or unchallenged in European towns and cities?