Earlier this week I spent some time at the Bibliotheque Historique de la Ville de Paris as part of my investigations into the history of urban nature. I had already found some interesting studies of plants growing in and around Paris from the nineteenth century but then noticed a record of a much earlier book from 1698. After waiting a few minutes with a sense of expectation in the library’s elegant reading room the old book was brought out for me to see and placed on a special kind of velvet cushion along with small weights to help open the pages. As I opened the first page I felt a sense of astonishment and delight: this is exactly what I had been looking for. Lying somewhere between a scientific treatise and a popular guide to wild plants I found myself immersed in a different yet recognizable world: many of these plants already had vernacular names along with an early pre-Linnean system of scientific nomenclature. The book itself made reference to over 60 further works providing a kind of compendium of botanical knowledge in Europe at the time. Place after place mentioned in the text was either familiar to me or easily locatable on the map. I felt as if I was accompanying the author, Pitton Tournefort, through the landscapes of Paris and its environs at the end of the seventeenth century.

Category: blog

Inside out: Vermeer, de Hooch and the interior landscape

I set off in the winter gloom yesterday to see a small exhibition of the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer and some his contemporaries at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Given that so few of Vermeer’s paintings still exist it was wonderful to see four in one go alongside a range of lesser known artists such as Gerard ter Borch and Nicolaes Maes, as well as more familiar works by Pieter de Hooch and Jan Steen. The exhibition entitled Vermeer’s women: secrets and silence focuses on the depiction of women in a series of interior settings engaged in various tasks ranging from household chores to more contemplative moments reading, writing or playing music. Many of these paintings — which deploy various strategies in achieving different level of realism — consist of frames within frames: windows, doorframes, picture frames, linked courtyards (as in de Hooch) and other elements that emphasize our immersion in an interior and largely private landscape of domesticity that is dominated by the presence of women.

Seeing these paintings gathered together it is interesting to consider whether Vermeer’s pre-eminence within seventeenth-century Dutch art has been simply a quirk of canon formation or a real reflection of his better work. With the partial exception of de Hooch this exhibition shows that Vermeer was way ahead of his contemporaries. The structure of his compositions is less cluttered and by tending towards abstraction Vermeer paradoxically emphasizes the faithfulness of his works to human perception since our eyes shift their focus within any given frame to emphasize certain elements over others: in this way what we actually see is as much a reflection of our mind as what is actually there before us. In works such as The lacemaker (c. 1670) and The music lesson (c. 1662-3) there is a use of variation in soft and sharp focus to directly emulate and at the same time subtly guide the human eye. His works also lack elements of whimsy or Arcadian motifs lurking in some of his contemporaries: the exterior view in Conelis de Disschop’s rather dreary Girl peeling apples (1667), for example, depicts not a Dutch town but what appears to be some ivy-clad Italianate ruins. Most significant of all, however, is Vermeer’s use of light, which is so effective and so meticulous that it reveals not just the shimmering beauty of everyday objects or the human figure deep in contemplation but also works as a deeper metaphor for human thought and creativity itself.

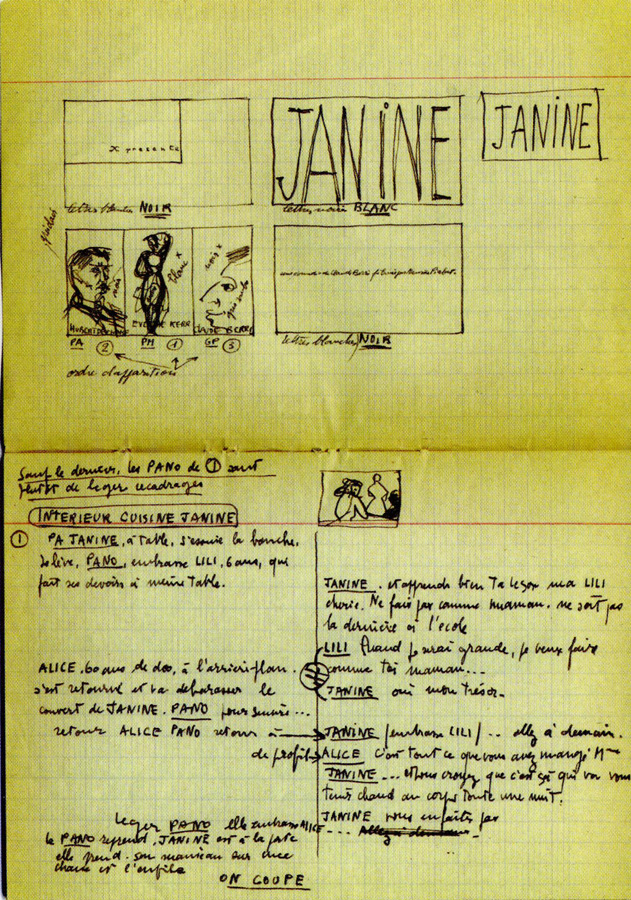

Maurice Pialat’s realism

The French film director Maurice Pialat (1925-2003) did not make many films but left a distinctive cinematic legacy. We could say that Pialat is a “humanist” film maker in the sense that he explores universal themes such as death, desire and jealousy, yet these are presented through the specific cultural lens of post-war France. Though less well known than his contemporaries such as Eric Rohmer, who also examines intricate aspects to everyday life, Pialat remains one of the most powerful and thought provoking of European film directors.

Pialat achieves a heightened sense of realism by a loose style of direction that allows for improvisation and the incorporation of les choses du moment [fleetings things]. As an actor himself Pialat also deploys the deliberate use of surprise to create provocative situations: his abrupt return as the estranged father in A nos amours [To our romance] (1983), for example, was not revealed to his cast so that they share in our own bewilderment. Another very interesting feature, that is reminiscent of the American film director John Cassavetes, is his focus on “real time” social situations: the intense conversation between mother and adult son after her cancer diagnosis in his study of death, La guele ouverte [The mouth agape] (1974), is marked by a series of silences, glances and inscrutable facial gestures. For Pialat, the presence of impending death serves as a catalyst that exposes the raw fragility of human relationships, provoking outbursts of anger, desire, laughter and despair. In La guele ouverte, the documentary feel to the film, with its unpretentious and fine-grained emphasis on detail, is also enhanced by the presence of several non-professional actors. Above all, Pialat presents us with an emotional realism that few other directors can rival.

Cloud formations: landscape and politics in the art of Gerhard Richter

The German artist Gerhard Richter, who has a major current retrospective passing through London, Berlin and Paris, has been producing some of the most interesting explorations of landscape since the 1960s. Richter provides a subtle counter point to the leaden sweep of European romanticism by reworking a whole range of familiar motifs such as mountains, forests and cloud formations to emphasize their perceptual and intellectual limitations as sources of certainty or truth.

His extensive use of blurring highlights the degree to which we try to read meaning into landscape: the way swirling clouds or the scatter of light across the forest floor can set off any number of possible patterns or permutations. Like the colour play of late nineteenth-century neo-impressionists, and their attempt to convey a higher level of visual realism in nature, we find that Richter is keen to explore the infinite possibilities of human perception. His distrust of ideological metaphysics places him far apart from the neo-romanticist lineage of Heidegger, Beuys and their postmodern progeny.

Working at the interface of painting and photography Richter has created a series of powerful juxtapositions: his aerial rendition of Paris, for example, is suggestive of a bombed out shell, reminiscent of post-war Cologne or Dresden, whilst his blurred Baader-Meinhof series emphasizes our lack of understanding of terrorism and the effects of ideology. His exquisite portrait paintings reference the seventeenth-century realism of Vermeer and his attempt to achieve new levels of technical perfection. In Richter’s hands, the practice of painting forms part of on-going dialogue with other forms of representation that range from the seventeenth-century camera obscura to the advent of digital photography.