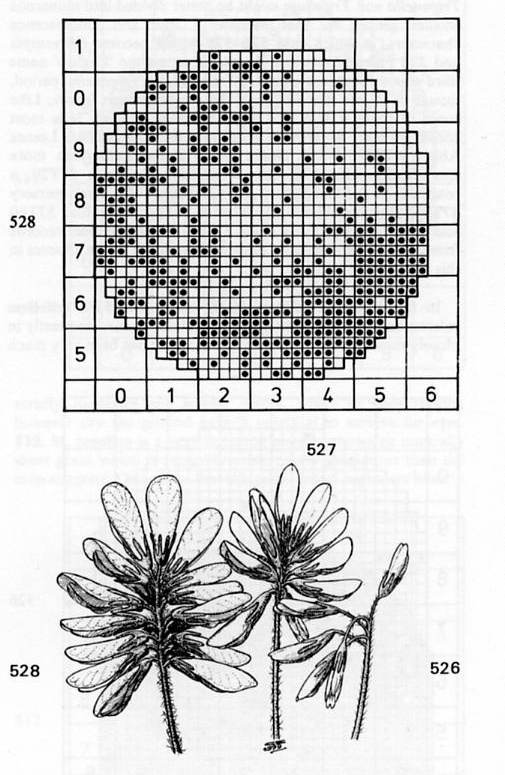

Earlier this week I spent some time at the Bibliotheque Historique de la Ville de Paris as part of my investigations into the history of urban nature. I had already found some interesting studies of plants growing in and around Paris from the nineteenth century but then noticed a record of a much earlier book from 1698. After waiting a few minutes with a sense of expectation in the library’s elegant reading room the old book was brought out for me to see and placed on a special kind of velvet cushion along with small weights to help open the pages. As I opened the first page I felt a sense of astonishment and delight: this is exactly what I had been looking for. Lying somewhere between a scientific treatise and a popular guide to wild plants I found myself immersed in a different yet recognizable world: many of these plants already had vernacular names along with an early pre-Linnean system of scientific nomenclature. The book itself made reference to over 60 further works providing a kind of compendium of botanical knowledge in Europe at the time. Place after place mentioned in the text was either familiar to me or easily locatable on the map. I felt as if I was accompanying the author, Pitton Tournefort, through the landscapes of Paris and its environs at the end of the seventeenth century.

Author: Matthew

Inside out: Vermeer, de Hooch and the interior landscape

I set off in the winter gloom yesterday to see a small exhibition of the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer and some his contemporaries at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Given that so few of Vermeer’s paintings still exist it was wonderful to see four in one go alongside a range of lesser known artists such as Gerard ter Borch and Nicolaes Maes, as well as more familiar works by Pieter de Hooch and Jan Steen. The exhibition entitled Vermeer’s women: secrets and silence focuses on the depiction of women in a series of interior settings engaged in various tasks ranging from household chores to more contemplative moments reading, writing or playing music. Many of these paintings — which deploy various strategies in achieving different level of realism — consist of frames within frames: windows, doorframes, picture frames, linked courtyards (as in de Hooch) and other elements that emphasize our immersion in an interior and largely private landscape of domesticity that is dominated by the presence of women.

Seeing these paintings gathered together it is interesting to consider whether Vermeer’s pre-eminence within seventeenth-century Dutch art has been simply a quirk of canon formation or a real reflection of his better work. With the partial exception of de Hooch this exhibition shows that Vermeer was way ahead of his contemporaries. The structure of his compositions is less cluttered and by tending towards abstraction Vermeer paradoxically emphasizes the faithfulness of his works to human perception since our eyes shift their focus within any given frame to emphasize certain elements over others: in this way what we actually see is as much a reflection of our mind as what is actually there before us. In works such as The lacemaker (c. 1670) and The music lesson (c. 1662-3) there is a use of variation in soft and sharp focus to directly emulate and at the same time subtly guide the human eye. His works also lack elements of whimsy or Arcadian motifs lurking in some of his contemporaries: the exterior view in Conelis de Disschop’s rather dreary Girl peeling apples (1667), for example, depicts not a Dutch town but what appears to be some ivy-clad Italianate ruins. Most significant of all, however, is Vermeer’s use of light, which is so effective and so meticulous that it reveals not just the shimmering beauty of everyday objects or the human figure deep in contemplation but also works as a deeper metaphor for human thought and creativity itself.

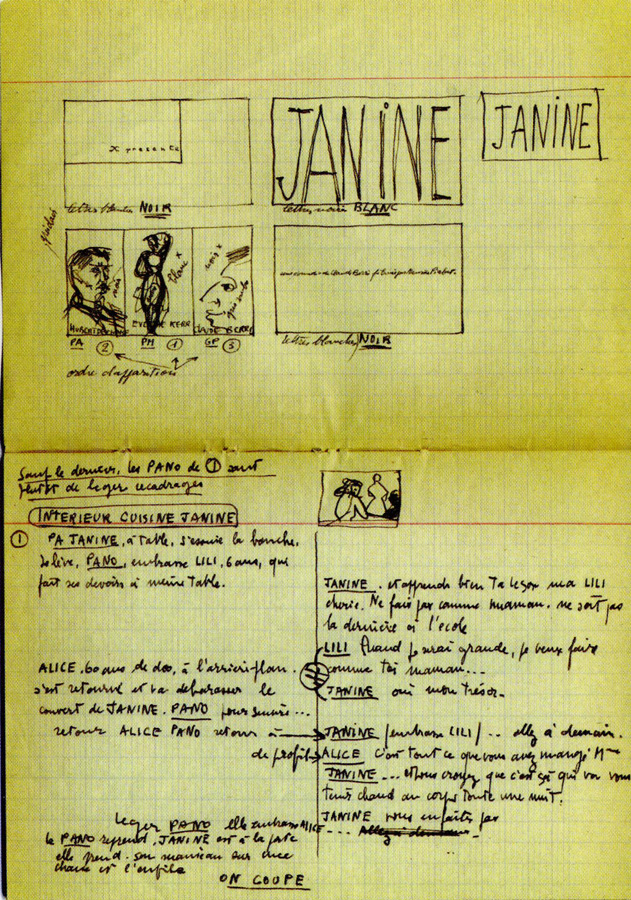

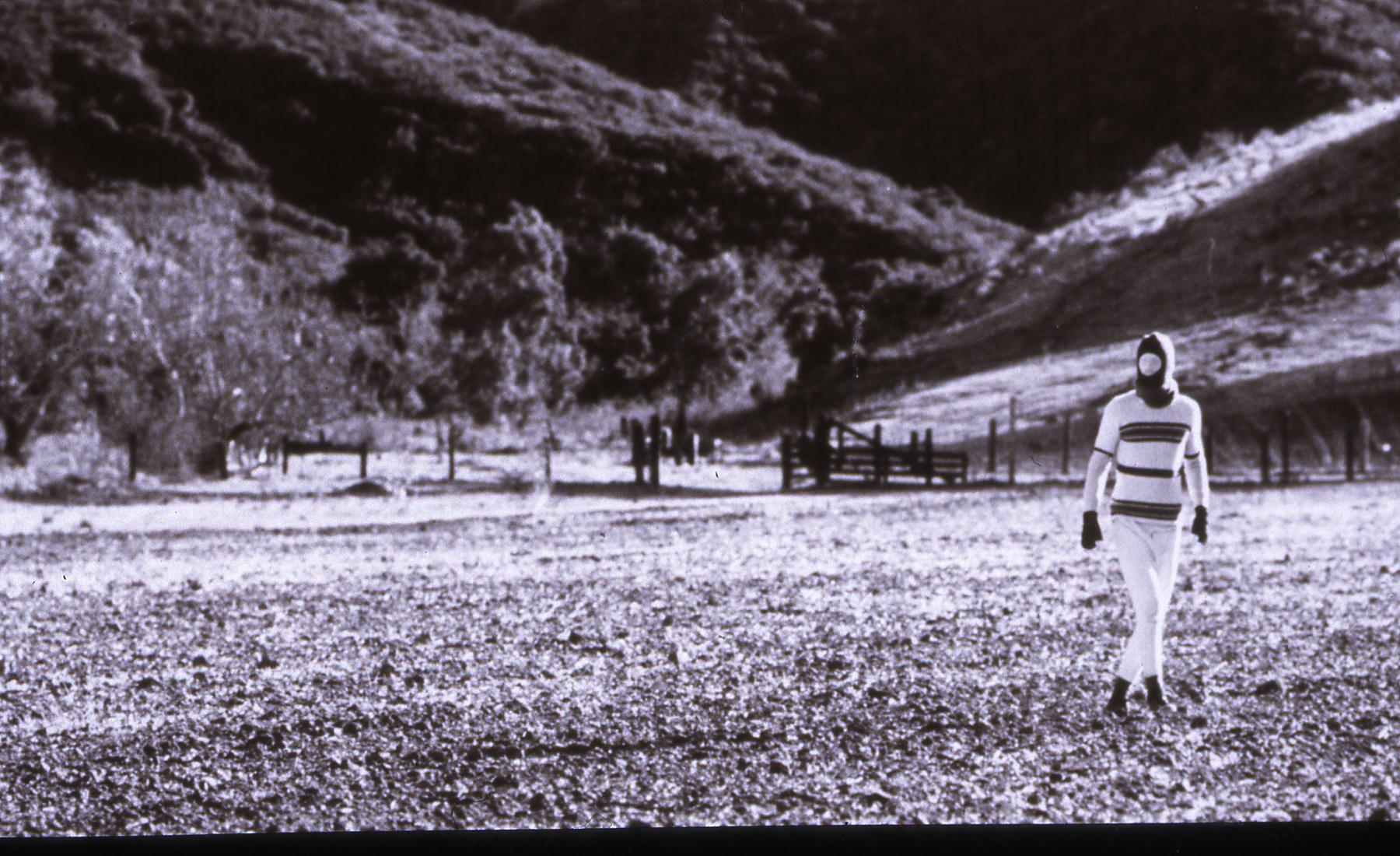

Maurice Pialat’s realism

The French film director Maurice Pialat (1925-2003) did not make many films but left a distinctive cinematic legacy. We could say that Pialat is a “humanist” film maker in the sense that he explores universal themes such as death, desire and jealousy, yet these are presented through the specific cultural lens of post-war France. Though less well known than his contemporaries such as Eric Rohmer, who also examines intricate aspects to everyday life, Pialat remains one of the most powerful and thought provoking of European film directors.

Pialat achieves a heightened sense of realism by a loose style of direction that allows for improvisation and the incorporation of les choses du moment [fleetings things]. As an actor himself Pialat also deploys the deliberate use of surprise to create provocative situations: his abrupt return as the estranged father in A nos amours [To our romance] (1983), for example, was not revealed to his cast so that they share in our own bewilderment. Another very interesting feature, that is reminiscent of the American film director John Cassavetes, is his focus on “real time” social situations: the intense conversation between mother and adult son after her cancer diagnosis in his study of death, La guele ouverte [The mouth agape] (1974), is marked by a series of silences, glances and inscrutable facial gestures. For Pialat, the presence of impending death serves as a catalyst that exposes the raw fragility of human relationships, provoking outbursts of anger, desire, laughter and despair. In La guele ouverte, the documentary feel to the film, with its unpretentious and fine-grained emphasis on detail, is also enhanced by the presence of several non-professional actors. Above all, Pialat presents us with an emotional realism that few other directors can rival.

Cloud formations: landscape and politics in the art of Gerhard Richter

The German artist Gerhard Richter, who has a major current retrospective passing through London, Berlin and Paris, has been producing some of the most interesting explorations of landscape since the 1960s. Richter provides a subtle counter point to the leaden sweep of European romanticism by reworking a whole range of familiar motifs such as mountains, forests and cloud formations to emphasize their perceptual and intellectual limitations as sources of certainty or truth.

His extensive use of blurring highlights the degree to which we try to read meaning into landscape: the way swirling clouds or the scatter of light across the forest floor can set off any number of possible patterns or permutations. Like the colour play of late nineteenth-century neo-impressionists, and their attempt to convey a higher level of visual realism in nature, we find that Richter is keen to explore the infinite possibilities of human perception. His distrust of ideological metaphysics places him far apart from the neo-romanticist lineage of Heidegger, Beuys and their postmodern progeny.

Working at the interface of painting and photography Richter has created a series of powerful juxtapositions: his aerial rendition of Paris, for example, is suggestive of a bombed out shell, reminiscent of post-war Cologne or Dresden, whilst his blurred Baader-Meinhof series emphasizes our lack of understanding of terrorism and the effects of ideology. His exquisite portrait paintings reference the seventeenth-century realism of Vermeer and his attempt to achieve new levels of technical perfection. In Richter’s hands, the practice of painting forms part of on-going dialogue with other forms of representation that range from the seventeenth-century camera obscura to the advent of digital photography.

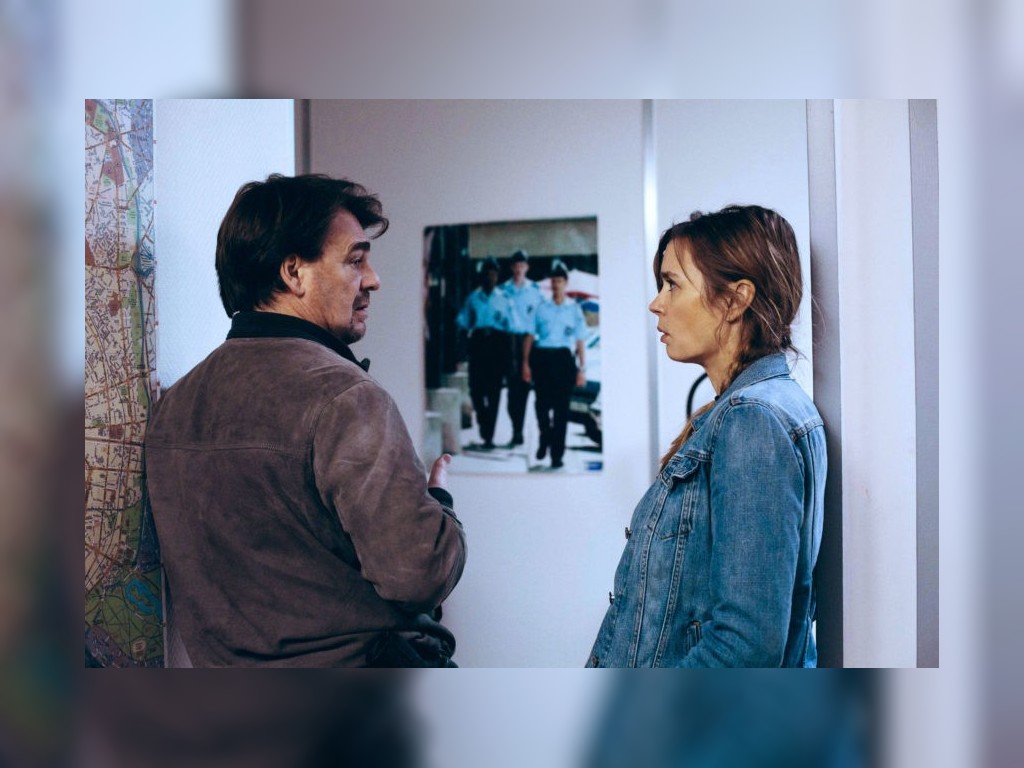

Engrenages [Spiral]

The French TV drama Engrenages — released as Spiral for English-speaking audiences — inhabits a terrain somewhere between the Baltimore depicted in the The Wire and the Copenhagen of Forbrydelsen [The Killing]. Set in contemporary Paris, Engrenages is based around a series of grisly crime investigations that evoke a dark archaeology of the city as a nest of corruption, deceit and violence. The pivotal character is undoubtedly the police captain Laure Berthaud, played superbly by Caroline Proust, who fearlessly pursues her opponents with a combination of recklessness and vulnerability. The “baddies” that we encounter are a truly remarkable menagerie of monsters, ranging from corrupt lawyers to various psychopathic murderers, who at times correspond to various pre-conceived stereotypes ranging from Arab hustlers to eastern European pimps. At a political level, therefore, the drama is not particularly incisive: unlike the multi-layered Baltimore of The Wire we never get a compelling sense of how Paris works as a city. Many of the characters are too one-dimensional for us to invest much emotionally in their respective fates and the lines of sexual and racial difference evoke little more than a claustrophobic ambience of danger and paranoia. Ironically, Engrenages owes too much to second-rate crime dramas and not enough to more experimental TV drama. For a city that is as much shaped by its post-colonial present as its imperial past the Paris of Engrenages seems somewhat limited in its scope.

Cosmopolitan urbanism

Out of curiosity today I checked the etymology of the word “cosmopolitan” and found that it is of seventeenth-century French origin, derived from the Greek word kosmos meaning “world” and polites meaning “citizen”. The word “cosmopolis”, which combines kosmos with polis (the Greek work for city), appears to have first been used in the nineteenth century. So the ideas of world, citizen and city come together through these words and appear to offer an alternative set of ideas to that of an urbanism determined by boundaries, distinctions and exclusions. An enlightened conception of urban citizenship can be conceived as a form of belonging or identification that lies in contradistinction to more narrowly defined notions of ethnic, religious or nationalist affiliation. But who are cities for? Has the progressive promise of the “open city” been captured by transnational elites? Can a liberal city also be a just city in both social and economic terms? A cocktail in a swanky neon-lit bar in downtown Bombay/Mumbai can cost more than the debt that may drive a farmer on the urban fringe to suicide.

The historian Mark Mazower argues that the rise of ethnically defined nation states in the twentieth century, combined with the rise of European fascism, led to the brutal reorganization of previously mixed cities such as Salonica (now Thessaloniki) in Greece. One of the calamitous side effects of Western intervention in Iraq was the destabilization of the mixed character of Baghdad and other cities as new forms of religiosity were unleashed.In Nigeria, for example, there are latent tensions between “generous urbanism”, and the absorption of economic migrants and refugees from elsewhere in Nigeria and West Africa, and underlying ethnic or religious tensions that can easily be exploited. It is striking, however, that in spite of everything, cities remain relatively safe havens from poverty or violence in comparison with their rural hinterlands. Yet under such intense and uncertain conditions, especially in the global South, it remains to be seen whether cosmopolitan urbanism can vie successfully with its intolerant alternatives.Just as cities can also serve as the fulcrum for progressive change they can also serve as citadels of injustice and repression.

Mark Mazower, Salonica. City of Ghosts. Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 (Harper Collins, London, 2004).

Britain on the edge of Europe

Last night the British Prime Minister David Cameron held a celebratory dinner party with right-wing MPs after he used his veto against closer European political cooperation to stabilize the euro which has left Britain more isolated within Europe than at any time in the post-war era. It seems that the upsurge of “Europhobia” fostered by the current government and their media allies has led to a situation where foreign policy is being driven by a few dozen MPs agitating to take Britain out of the European Union along with the lobbying of the financial services sector to prevent the possibility of tighter regulation or the imposition of a transaction tax. Meanwhile, pro-European voices across Britain have been muted and scattered as the longer-term implications of this debacle have yet to be widely recognized. For many in the Conservative Party these events mark the first steps towards a national referendum and the longed for exit from the EU altogether. Isolationist fantasies are gathering momentum as if Britain might be transformed into a larger version of Switzerland.

Britain’s antipathy towards Europe can be read as a kind of neo-colonial fantasy of imagined grandeur: it is interesting to contrast Ireland’s embrace of Europe with that of the UK. Indeed, an independent Scotland, as Alex Salmond points out, would seek closer ties with Europe. Although Cameron’s move appears superficially to safeguard the financial services sector of the UK economy the rationale for London’s economic role within Europe looks set to change as the relative importance of Frankfurt, Paris and other cites begins to grow. The apparent strength of Britain’s separate currency is built on shaky foundations and as the strengthened eurozone pulls away in coming years the economic and political marginalization of the UK looks set to intensify. My political antennae tell me that the eurozone will not break up: one or two countries may partially or even completely default but the overall project has too much political capital invested in it to fail. More broadly, however, we need to rebuild political legitimacy for a progressive European project that can demonstrate real benefits for its people. The underlying tensions between technocratic austerity and neo-Keynesian strategies for growth have not been resolved.

The texture of space

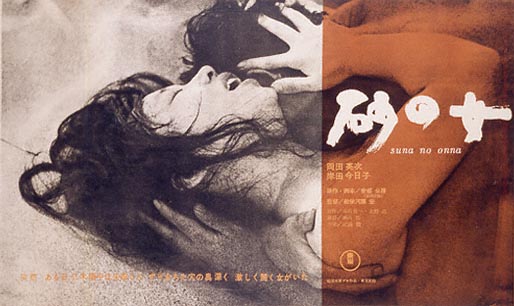

‘The texture of space: desire and displacement in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman of the dunes [Suna no onna],’ in Douglas Richardson, Stephen Daniels, Dydia de Lyser and Nick Entrikin (eds.) Geography and the humanities (London and New York: Routledge) pp. 198–208.

Science, nature and the public realm

The current political emphasis on greater accessibility and public engagement in relation to urban nature raises certain difficulties. Professional botanists, entomologists and other scientists tell me that public policy towards biodiversity and the protection of “wild nature” is being driven increasingly by a public-relations emphasis on certain “flagship species” or vague notions of sustainability rather than detailed knowledge about sites, species and the ecological dynamics of urban space. Those agencies charged with the protection of nature or the fostering of environmental education often lack any specialist expertise leading to a repeated emphasis on a small number of easily recognizable animals or plants. The idea that deeper knowledge requires years of patience and dedication has been supplanted by a culture of immediacy. In such circumstances how can cultural or scientific complexity be effectively communicated? What happens when autonomous criteria for scientific evaluation conflict with externally imposed agendas for reshaping knowledge? The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls for the defence of the “inherent esotericism of all cutting-edge research” yet he also insists on the development of appropriate strategies for the scientific enrichment of the public realm.1 In the case of urban ecology there is a glaring disjuncture between specialized scientific understandings of urban space and mediated discourses of consumption.

To open a wasteland

The Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui has a wonderful photo entitled “To open a wasteland” that depicts some kids rushing into a patch of waste ground in Brussels. The sense of an urban enclosure being revoked is captured in the blurred movement of figures surging forward.

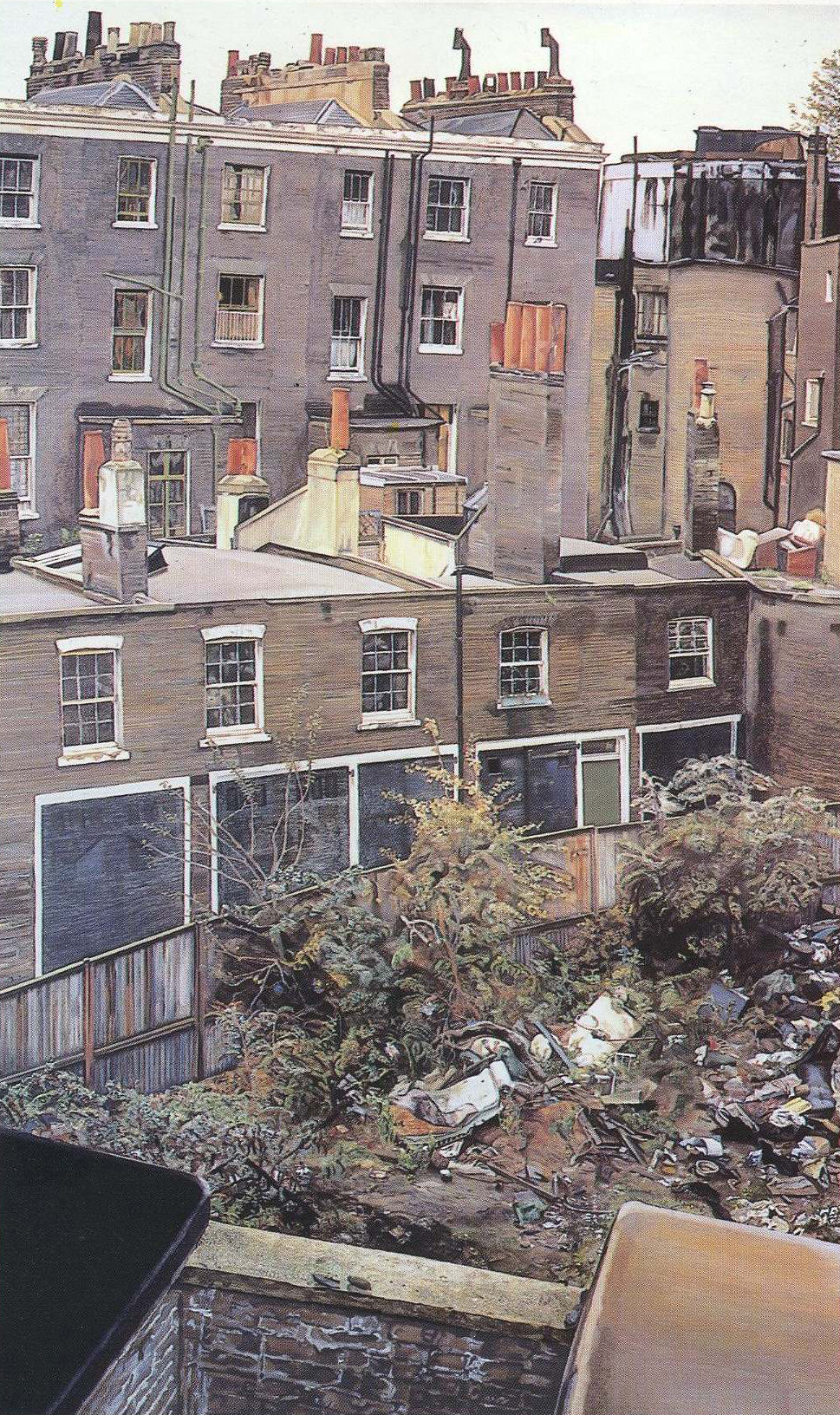

I think I first reflected on the presence of “enclosed” waste spaces in cities whilst writing about Lucien Freud’s Wasteground with Houses, Paddington (1970-2) which provides a view from the window of his West London studio. Freud depicts the rear elevation of shabby Victorian terraces, with their jumble of aerials and chimneypots, interspersed with an area of overgrown wasteland. So precise is his painting that we can identify many of the plants he observes.

From my office window at UCL in central London a few years ago I noticed a similar anomalous space that had developed spontaneously between other buildings. As I looked down one winter afternoon a fox sauntered past and in summer the honey-scented flowers of Buddleia davidii are visited by bees and butterflies. This summer I decided to pursue my curiosity further and arrange access to the site. After opening a metal gate I made my way up some slippery rubbish-strewn steps and entered a strange world of tangled vegetation. Accompanied by the artist Carolyn Deby and the botanist Nick Bertrand we surveyed the site, finding over thirty species of plants, including three kinds of oak trees. Nick’s expertise was inspirational as he pointed out different species that had colonized the site. A seemingly empty space was brimming with life.

What struck me immediately was that this space has become a kind of miniature urban forest with its own mix of plants from all over the world. Instead of looking down onto the site I was now looking up at the brutalist façade of the university building with leaves touching my face. For a moment I became aware of myself at another point in time gazing distractedly from my window just metres away.

This afternoon, however, I glanced towards the site and noticed that it has just been cleared, leaving an expanse of rubble with a few plants left where they could not be scraped away by heavy machinery. The cycle of entropy and ecological succession must begin anew amid the vagaries of urban development and yet another planning application.

Let England shake: PJ Harvey at the Royal Albert Hall

Polly Jean Harvey, currently artist-in-residence at the Imperial War Museum, played a sold-out gig last night at London’s Royal Albert Hall. There was an unmistakable buzz about the venue as the cavernous auditorium filled to capacity amid a roar of excited conversation.

And then the lights dimmed and she was there. Dressed in black, and standing to one side of her small backing band, she briskly played the whole of her prize-winning new album. Although the acoustics of the space are famously muddy her searing anti-war lyrics were clearly audible, the words leaping from the shadows, and providing a poignant contrast with more jingoistic connotations of the venue. Though a response to contemporary wars, PJ Harvey’s latest work draws on the elegiac futility of the First World War as a symbol for all wars, and the shattering and splintering of young lives. “Soldiers fell like lumps of meat,” she sings to the incessant rhythm of “The words that maketh murder”. It is not just the mist-shrouded battlefields, swarming with flies, that Harvey evokes, but also the poisoning of England itself:

Let me walk through the stinking alleys

to the music of drunken beatings,

past the Thames River, glistening like gold

PJ Harvey is an uncompromising artist: critically acclaimed yet meeting with only modest commercial success. She exemplifies a paradoxical outcome of the political economy of music marked by a renewed re-orientation towards live performance: since it is increasingly difficult to make money from selling music, or even control the sequence of tracks on an album, the artist must look towards the live performance not just to sustain their living but also as a means to impose their artistic vision: for Harvey to play her new album in its entirety is a real-time artistic statement of how it should be heard. In the encore, however, she delves into her back catalogue, with mesmerizing renditions of “White Chalk” and “Angeline” that send shivers down the spine.

Hævnen

The Danish film Hævnen (2010), also released under the English title of In a Better World, is a real gem. Directed by Susanne Bier, Hævnen, meaning revenge in Danish, is a subtle and powerful exploration of anger, grief and violence.

A bullying incident at school invokes a brutal retaliation that leaves us feeling decidedly uneasy: the bullied boy’s new friend is struggling with grief over his mother’s death which he channels into a ferocious assault on the school bully. We want a decisive retaliation but the incident goes too far. At this point the film bears some initial similarities with David Cronenberg’s A history of violence (2005), but in Hævnen the sense of emotional tension is sustained throughout and there is no descent into cartoon mobsterism.

The bullied boy’s father, played superbly by Mikael Persbrandt, is also caught in an ugly street incident watched by his son and his new friend (and protector). The father is slapped and insulted by an aggressive stranger but does not retaliate. He tries to explain that his passivity is a sign of strength but his son and his friend cannot accept this and secretly plan a revenge attack of their own.

As a parallel narrative, the father of the bullied boy works regularly as a doctor in a refugee camp in war-torn east Africa: a few days later he is faced with the moral dilemma of treating a man who has brutally attacked women in nearby villages. After his treatment, however, the man begins to taunt the doctor over his crimes and in a sudden rage the doctor pushes him to the ground. It is a striking and extraordinary scene that profoundly tests our emotional response to anger.

Using the tranquil Danish countryside as a backcloth Hævnen is a multi-faceted exploration of how anger drives and distorts human relationships. Bier presents a much more effective exploration of violence than Cronenberg because she detects the incipient traces of violence all around: there is a pervasive sense of fury that leaps like sparks between the main protagonists. The eventual denouement, following the boys disastrous attempt to avenge the street incident, is all the more powerful because we have grown to know the complexities of the individual characters and we as an audience have made an emotional investment in the final outcome.

Earth [Zemlya]

At the BFI Southbank today I had the chance to see Alexander Dovzhenko’s rarely shown silent film Earth [Zemlya] accompanied by live piano music. Made in the summer of 1929 in rural Ukraine the film opens with a swirling sea of wheat that is reminiscent of Terrence Malick’s Days of heaven (1978). This is followed by a series of delicate images of human faces, sunflowers and apples. The low position of the camera lends the human faces a “heroic quality” outlined against the vast sky.

The core theme is the coming collectivization of Soviet agriculture centred on the arrival of the first tractor — the “iron horse of Bolshevism” — and the latent tensions between peasants and kulaks. For contemporary Stalinist critics, however, Earth was not considered political enough and Dovzhenko was widely vilified for his lyrical and sensuous vision. By the film’s release in 1930 the brutal aspects to collectivization were becoming increasingly apparent and the idyllic landscapes depicted in Earth were to become spaces of devastation.

In the closing scenes we see apples, melons and pumpkins in the rain. Yelena, the bereaved wife of the young farmer Vassili, has found a new lover. And the poetic qualities of the film leave us to reflect on time, nature and the yearning for a “new life”.

Fish Tank

In Andrea Arnold’s extraordinary film Fish Tank, first released in 2009, we encounter the landscapes of Rainham on the London/Essex border experienced largely through the eyes of fifteen-year old Mia, played to incredible effect by the unknown actor Katie Jarvis, who was apparently spotted by the casting agent on a railway platform. Though Rainham is not quite an explosive banlieue in the French sense it is nonetheless portrayed as a space of intense social and cultural marginality.

In Fish Tank Arnold builds a profoundly claustrophobic mood that is matched by an oppressive “edge” landscape of utilitarian functionality dominated by highways, pylons and superstores. In perhaps the most striking scene, however, Mia, along with her mother, her younger sister, and her mother’s new boyfriend, enter a hidden space of “wild urban nature” where they encounter the beauty of nature, symbolized by the fleeting appearance of a blue damselfly by the edge of a small lake.

Arnold may well be the most exciting contemporary British film director. There is an enigmatic dimension to her work — also reflected in Red Road and the short film WASP — that builds a sense of emotional complexity and unpredictability. Her cinema attains a certain kind of vivid realism that is rooted in an uncompromising corporeality combined with an exploration of the inner foment of her cinematic protagonists.

Is terrain vague a vague concept? Reflections from Brussels

A couple of weeks ago I attended a conference in Brussels and was intrigued by an “empty space” just next where I was staying in the centre of the city. Bordering the busy Avenue de la Toison d’Or is a large plot of land — overlooked by billboards announcing the imminent “city of tomorrow” — that is currently a jumble of rubble and weeds fenced off from the rest of the city. Having climbed through the wire mesh on a bright Sunday morning I wondered whether this might be the kind of space that the Spanish architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales has termed terrain vague.

In an essay published in the collection Anyplace, Solà-Morales sets out his definition of terrain vague in some detail. He begins by locating the concept within the history of urban photography:

“Empty, abandoned space in which a series of occurrences have taken place seems to subjugate the eye of the urban photographer. Such urban space, which I will denote by the French expression terrain vague, assumes the status of fascination, the most solvent sign with which to indicate what cities are and what our experience of them is.”

Having explored the origins of the word vague and its “triple signification” as “wave”, “vacant” and “vague” he then adds:

“Unincorporated margins, interior islands void of activity, oversights, these areas are simply un-inhabited, un-safe, un-productive. In short, they are foreign to the urban system, mentally exterior in the physical interior of the city, its negative image, as much a critique as a possible alternative.”

And then a few paragraphs later the crucial sentence that seems to capture perfectly the essence of this plot of ground in Brussels:

“When architecture and urban design project their desire onto a vacant space, a terrain vague, they seem incapable of doing anything other than introducing violent transformations, changing estrangement into citizenship, and striving at all costs to dissolve the uncontaminated magic of the obsolete in the realism of efficacy.”

The concept of terrain vague seems, however, to be overwhelmingly visual in its scope. It is difficult to connect the essentially aesthetic response of Solà-Morales to a consideration of how such anomalous spaces appear and disappear within the city and how they might connect with or illuminate wider processes of urban transformation. In the case of the Brussels quarter of Ixelles/Elsene this is an area that is undergoing rapid change: a vibrant predominantly Congolese community is being gradually squeezed out, house by house, to enable a new kind of “international city” to be created. In fairness to Solà-Morales his concept is rooted in the history and theory of urban photography but how do images intersect with urban theory? And what can “territorial indications of strangeness” — to use another phrase of Solà-Morales — actually reveal about the urban process? It may be that terrain vague cannot easily be used in isolation and is best considered as one of a number of interesting terms that adds to the lexicon of urban thought. And of course there is a contradiction to my response to Solà-Morales since I am also wandering around the streets of a city I hardly know with a camera in my hand.

Urban islands: Parc Henri-Matisse, Lille

A few days ago I emerged from Lille eurostar station and stepped into one of the most interesting parks in Europe. Completed in 1995 as part of the vast Euralille project, Parc Henri-Matisse combines an expansive open field with a raised island at its centre. The eight hectare park was designed by the French horticulturalist and landscape architect Gilles Clément, who has been at the forefront of recent attempts to include the spontaneous dynamics of nature in urban landscapes. Since the 1970s Clément has been studying the aesthetic and scientific characteristics of spontaneous ecological assemblages such as fallow land to explore how these “gardens in movement” might be incorporated into the design of parks and gardens. A key concept he has advanced is that of the “third landscape” which includes all those spaces that lie outside of cultivation or direct human use and are often important for the maintenance of biodiversity. In Parc Henri-Matisse the idea of the “third landscape” has been put into practice through the creation of an artificial island that will serve as a long-term refuge for urban biodiversity. Clément has named this structure Derborence Island after a fragment of primary forest in Switzerland that has survived virtually intact over thousands of years because of its remote location. Similarly, in Parc Henri-Matisse the central island has been made completely inaccessible like a vast sculpture or enigmatic monument. The oddity of this overgrown concrete block has not been without its critics, however, who have derided its presence as a form visual intrusion that is antithetical to conventional conceptions of public space.

My impressions of the park in blazing May sunshine are that it is quite heavily used, especially by young people, couples and people on their own. The concrete island is surrounded on two sides by a semi-wild landscape of trees and small clearings, which provide a lush contrast with the more open formality of the grassy expanse to the south. The question whether the island really does serve a direct role in maintaining urban biodiversity is not yet certain and its purpose is perhaps more symbolic than ecological. If over time, however, a unique ecological assemblage really does emerge on top of this concrete plinth then perhaps the cultural and scientific aspects to the park’s design will begin to elide more closely. In fact, this may already be happening: just below the island I stumbled across a rare beetle, the bee-mimicking Trichius zonatus, that may conceivably be among those creatures whose urban presence is now being sustained by Derborence Island.

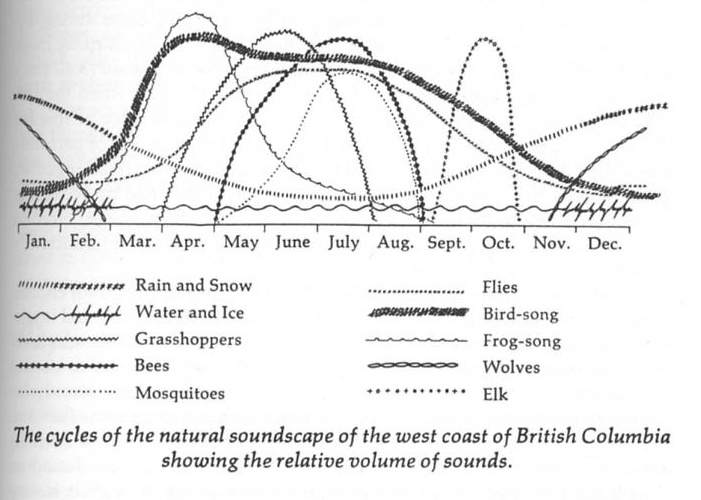

Soundscapes of late modernity

In his extraordinary book The soundscape: our sonic environment and the tuning of the world, first published in 1977, the Canadian writer and composer Murray Schafer exhorts us to listen more carefully to the world. He introduces an “acoustic ecology” that combines everything from history (the changing experience of sound) to physics (the properties of sound itself). His book is arranged very systematically with numerous diagrams as if to suggest that all aspects of sound can be brought within a framework of scientific logic. Central to his thesis is the claim that through understanding sound we can make better sense of human societies in all their complexity. More recently, the cultural theorist Stephen Connor has written of the “modern auditory I” to underline how sound connects with our sense of identity to produce “the sonic self”. Connor and other theorists show us how the presence of sound is constantly reconfiguring space and blurring boundaries.

At Cafe Oto in Dalston last Sunday I listened to a performance of electronic music featuring a series of leading musicians and sound artists: BJ Nilsen, Stephan Mathieu and the TSU duo of Jörg-Maria Zeeger and Robert Curgenven. TSU began with an unobtrusive hum that gradually built up to a frightening swell of sound that was at times simply deafening. I occasionally covered my ears and feared for my internal organs but convinced myself that extreme sound has its place in the pantheon of acoustic experience. Second on stage was BJ Nilsen who uses juxtapositions of music and ambient sound to create complex textures that often invoke very specific locales or fragments of memory. His material featured elements from his excellent album The invisible city that includes musical instruments combined with other sound sources such as amplified objects, bees and crows. Finally, Stephan Mathieu presented an intricate layering of harmonic landscapes. Using a combination of early instruments, obsolete technologies and freeform experimentation derived from abstract expressionism, Mathieu created an ethereal soundscape as different chord formations drifted in and out of focus. In contrasting ways all three performances explored the edges of contemporary sound and produced an experience that seemed an oddly appropriate cultural echo from east London to the prestigious Wigmore Hall north of Oxford Street where Beethoven, Shostakovich and Debussy were being played on the same evening. As I stepped out into the dusty street after the show I was immediately conscious of the noise of traffic, human voices and precisely the kind of complex soundscape that is incessantly around us.

Spreewald als Urwald

Less than 100 km south-east of Berlin, in the German state of Brandenburg, lies one of the most important ecosystems in Europe. Designated as a UN Biosphere Reserve in 1991, Spreewald (meaning “Spree forest” after the river Spree), consists of nearly 50 square kilometres of forests, marshes and farmland. The reserve is divided into four zones ranging from zone 1 which consists of agricultural land, the cultivation of which is closely overseen to protect the unique landscape, to zone 4, or the so-called “core areas” that cannot be entered. Much of the heavily forested landscape is criss-crossed by a dense network of streams interspersed with canals so that many localities can only be easily reached by boat. The area is also home to a Slavic minority — the Sorbs — who speak their own language and have maintained their cultural identity over many centuries.

Earlier this week I visited Spreewald and braved the mosquitoes to enter this strange “wilderness”. There are dense stands of alder, birch, oak and other trees and thick vegetation often gives the illusion of solid ground across the marshy landscape. There is birdsong all around — cuckoos, woodpeckers and many others I cannot identify — and frogs and snakes abound. Above all, this is an entomological paradise, especially for beetles which thrive on the vast array of dead wood at every stage of decay. If we were to seek out a pocket of “primary forest” or Urwald in contemporary Europe this must come pretty close even if it cannot match the vast scale of Białowieża in eastern Poland. Of course many of the large mammals that once roamed this landscape have long since gone: bears and wolves, for example, are no longer to be found.

But what is the draw of “primal nature” in the twenty-first century? For me it is undoubtedly a mix of romantic and scientific fascination to be immersed in such a place and find some rare or beautiful things and in some small way also contribute towards the still incomplete knowledge of the reserve’s biodiversity. What though is the pretext for protecting biodiversity? Utilitarian arguments tend to rest on features such as medicinal properties or the potential development of eco-tourism. Intrinsic arguments call for nature to be valued irrespective of its human use. In a sense both these arguments are somewhat misplaced: the utilitarians end up relying on some tortuous version of cost-benefit analysis to stake their claim whilst the intrinsic or ecocentrist arguments seem to cut off nature from culture or history (despite the human origins of such philosophical conjectures). A different and avowedly anthropocentric position might be that nature is worth protecting simply because it enriches human life in the same way as art or music.

From Forbrydelsen to Copenhagen

It’s strange to arrive in a city you already “know” yet have never visited. What brought me finally to Copenhagen this week, and to Denmark for the first time, was The Killing [Forbrydelsen], an extraordinary twenty-part TV drama which delves deep into the psyche of its main characters and is played out against a grey November skyline. Like the depiction of Baltimore in The Wire, the portrait of Copenhagen in The Killing explores many elements: the inner landscapes of grief, the spectre of racism, political chicanery, and above all, an emphasis on the complexity of human relationships.

On my first morning in Copenhagen I headed like many other visitors for Christiania, the alternative city within a city, that was established in a cluster of abandoned military buildings in 1971. This alternative community of 500-700 people — with its own decision-making structures — has had a turbulent relationship with the Danish state. A government decision to forcibly remove the settlement in 1975 was rescinded in 1976 following a wave of public sympathy. The commune has repeatedly struggled to prevent outsiders from using the site as a base for drug dealing: their semi-autonomous status being taken advantage of as a safe haven for crime. My first impressions of the rather shabby and commercialized cluster of shops and stalls by the main entrance is that this could be London’s Camden Lock Market. The “real” Christiania lies a further five minutes walk away where prettily decorated self-build homes and small gardens back onto the city’s canals. The urban sociologist Cecilie Juul tells me that the state is now trying to win their battle with Christiania by stealth: instead of taking the land by force they now propose to sell properties directly to their residents. Such a move undermines the possibility for shared ownership and will lead to a gradual “normalization” of property relations. As the original settlers from the 1970s die or move away the differences between this enclave and the rest of city will eventually fade away.

To the west of the city centre there is an interesting park called Ørstedsparken: the varied and naturalistic topography is reminiscent of Alphand’s Buttes-Chaumont or “the ramble” of Olmsted and Vaux’s Central Park. At the centre of the park is a lake encircled by fine trees and statues of mythical figures. The Ørstedsparken is interesting because it marks a changed relationship between the state and gay men: the role of the police has changed from that of harassment or entrapment to the protection of park users from homophobic violence. This is interesting because it underlies the “right to the city” in an inclusive way that signals an enlarged conception of the public realm as a shared space that encompasses many different interests. If the Ørstedsparken really is a heterotopia for sexual subcultures, in the Foucauldian sense of radical difference and social experimentation, then does the state’s role in protecting the park as “a space of difference” suggest a more complex relationship between “inside” and “outside” in contemporary societies?

A short distance north of Copenhagen lies the Louisiana gallery and sculpture garden. Clearly in an “art mood” as I waited for my train in the city’s central station I noticed that some fluorescent lighting on the station platform resembled a Dan Flavin installation. Louisiana is just a few minutes walk from the small town of Humlebæk and enjoys a perfect location next to the sea. How beautiful to see all these sculptures outside, nestled among trees, and within earshot of the waves below; each small clearing in the park brings surprises, every detour something different. Works by Jean Arp, Louise Bourgeois, Henry Moore and many others are gathered together in this magnificent setting. To see sculpture in this way is a remarkable experience that plays on all our senses and where distinctions between architecture, landscape and sculpture melt away.

An urban transect: the Regent’s Canal, London

The Regent’s Canal cuts through London like an urban transect. Walking east from Islington through Hackney towards Stratford yesterday I encountered a succession of changes in buildings, landscapes and other spaces. The back gardens of grand Victorian terraces gradually give way to light-engineering factories, film studios, lock keepers’ cottages and other spaces that have now been converted into luxury dwellings. The proximity of water in the post-industrial metropolis has fostered an accelerated set of architectural and cultural transformations yet remnants of the past remain.

The thriving canal-boat community of the Kingsland Basin is now encircled by new developments and the roar of construction activity. A mixed, socially inclusive and low-income London is being displaced, “decanted” or driven out to create a new kind of city.

Large swathes of social housing next to the canal have been removed or await their elimination. The Haggerston Estate, due to be demolished, has a poignant art installation in place, depicting former residents in their windows. The project “I am here”, by Andrea Luka Zimmerman, Lasse Johansson and Tristan Fennell, was in part a response to the negative characterizations of tenants which served as a pretext to enable the “redevelopment” of the site and the capture of waterside settings for wealthier Londoners

First Comma of spring

Yesterday morning I came across the first Comma butterfly of spring sunning itself near a busy road in north London. The Comma, Polygonia c-album, gets its name from a small white comma-shaped mark on the underside of its wings. Apparently first described in 1710 by the naturalist John Ray in his Historia Insectorum it was known by various names in the eighteenth century including the Silver, the Pale and the Jagged-wing.

Formerly very widespread in Britain during the nineteenth century it had by 1913 retreated to a narrow strip along the English-Welsh border. It then staged a dramatic and on-going comeback. One factor is undoubtedly a switch in larval foodplant away from hops — the cultivation of which declined steadily in the latter half of the nineteenth century — to the ubiquitous stinging nettle Urtica dioca to be found at the edge of fields, disturbed ground and almost anywhere where there has been human activity. Other factors may include climatic fluctuations but scientists remain perplexed about the full explanation.

La Vallée (Obscured by Clouds)

The British Film Institute recently screened a new print of Barbet Schroeder’s classic depiction of exploration and self discovery set in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. The film La Vallée (1972), also known as Obscured by Clouds, concerns a group of hippies who set out to discover a lost valley. The expression “obscured by clouds” refers to those areas that have never been cartographically surveyed since they are always blanketed in cloud.

Schroeder himself attended the BFI screening and referred to the film as “borderline, fiction, borderline documentary”. For Schroeder, what is interesting is not the final destination — which they never reach — but the journey itself as a symbol of dissolution for 1960s counter culture. He cited TS Eliot: “We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time”. In La Vallée the idealistic travelers become confused and disoriented: some of them imagine that they have found an understanding with nature and pre-modern culture but this proves to be a touristic chimera that provokes dissent within the group.

My interest in this film is not purely coincidental. Whilst studying geography at university I was sitting in a pub — I think it was the Eagle in Cambridge city centre — and a colleague mentioned that there was to be a research expedition to Papua New Guinea but one of the team had to drop out due to ill health. Without a second thought I said I would go. Some ten weeks later I was tramping through cloud forest — a distinctive kind of rain forest to be found at higher altitudes — and I remember the strange stillness of the moss-covered trees. One morning, just after dawn, I emerged from my tent and the cloud had temporarily cleared: there was ridge after ridge of green forest stretching out to the horizon.

The thing that I remember most vividly about Papua New Guinea was not the landscape, however, but the violence. Having stayed a few days in one of the villages some of the women began to tell me how terrible their lives were: the constant threat of domestic violence, the risk of rape while washing clothes by the river, and the perpetual state-of-war between different communities. Having been steeped in neo-Marxian literature at the time I realized that capital can only provide a partial explanation: questions of gender are of parallel if not greater significance. For the final part of my journey I went on alone to visit the Trobriand Islands off the coast of New Guinea, which proved to be a very different world. This was a matrilineal society based largely around farming and fishing. The men often wore hibiscus flowers in their hair and the aura of imminent violence was absent. It seemed clear that human culture could develop in any number of possible directions and that there is nothing innate about gender relations at all.

Cave of forgotten dreams

Werner Herzog’s latest film is a documentary about the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in the Ardèche region of southern France. The cave, first discovered in 1994, contains what are believed to be the oldest human paintings ever found, dating from over 30,000 years ago. The walls of the cave are festooned with intricate depictions of animals that would have roamed the glaciated landscapes of southern Europe at the time including bison, horses, lions, mammoths and rhinoceroses.

The film is visually spectacular, not least through the adoption of 3D technology to enhance the contours of the cave walls. The excellent cinematography enables us to look very closely at the remarkably preserved paintings along with the strange accretions of crystals and other geological features. The overall aesthetic effect is at times, however, rather bombastic or even operatic: Herzog’s own commentary begins to occlude the archaeological insights so that the documentary ends up being more about him than the cave itself.

Herzog’s work is marked by a tendency towards cinematic machismo. In one above-ground scene he mocks the spear-throwing ability of an archeologist that would have been no match for his distant ancestors (we can infer that Herzog rather fancied his chances of survival in the Paleolithic era). His mode of interviewing is marked by the use of leading questions — perhaps to a greater extent here than in his earlier documentaries — as he steers assembled scientists towards more speculative and metaphysical themes. The paintings, intones Herzog, represent nothing less than the origins of the human soul.

The film is also marred by an idiotic postscript featuring albino crocodiles inhabiting a giant greenhouse that uses waste water from a nearby nuclear power plant. With this final lapse into self parody — we also meet some of Herzog’s beloved reptiles in his recent “remake” of Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant — the documentary seems to lose its way and we are left with the director’s rambling insights into the human condition.

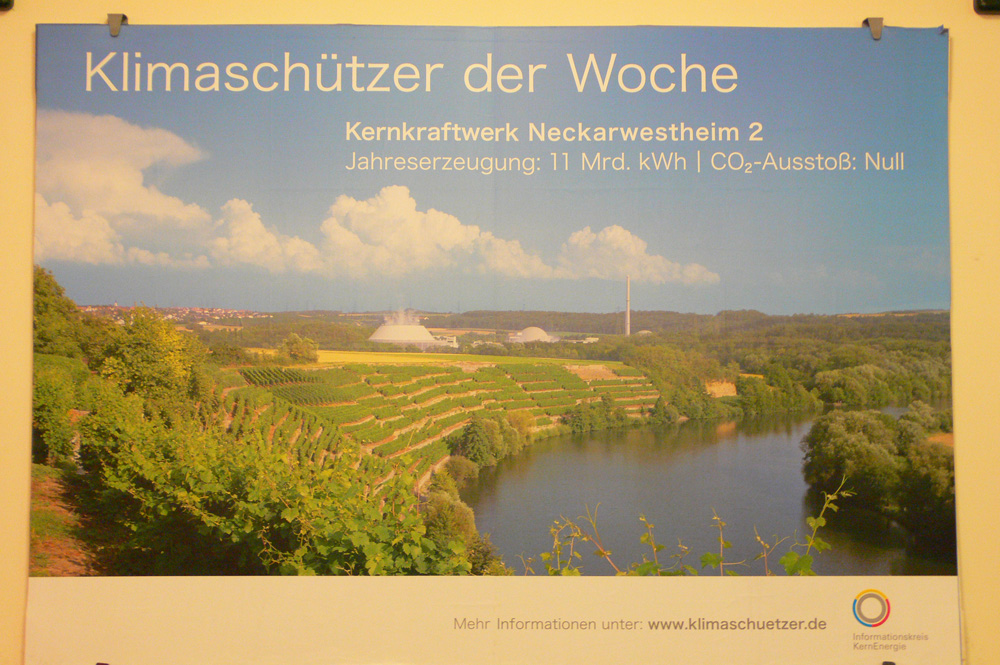

Nuclear power no thanks!

One of the first political issues I engaged with as a teenager was the debate over nuclear power: I decided against and have stuck to my position ever since. In the wake of the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 there was an extended interregnum in which no new plants were commissioned in Europe or North America: ostensibly on the grounds of cost — there was no profit to be made in nuclear power — but also because of continuing public unease and political opposition. The Chernobyl disaster of 1986 simply reinforced this sense of nuclear power as an anomalous and dangerous source of energy with cost, geo-political and environmental implications at every stage from uranium mining and enrichment to eventual de-commissioning and waste storage. Some of the engineering companies engaged in the building and operation of nuclear power plants began to concentrate on less contentious yet still controversial technologies such as waste incineration plants and other capital-intensive projects. It seemed that the nuclear option was in irrevocable decline.

With evidence of accelerated global warming, however, the nuclear industry have seized their chance over the last ten years, with intensive lobbying of governments to underwrite a new phase of expansion. Even high-profile environmental journalists such as George Monbiot appear to have swung behind nuclear power as the only feasible alternative to our continuing dependence on coal, oil and gas. I don’t accept the inevitability of the nuclear path for four reasons: firstly, the unfolding Fukushima disaster in Japan shows that nuclear power remains highly risky even in countries with sophisticated access to technological and regulatory expertise; secondly, as a source of electricity nuclear power only meets one aspect of our energy needs through an apparent “technological fix” that does not address the necessity for far greater emphasis on energy conservation and efficiency; thirdly, the potential contribution of renewable energy sources has been widely stymied; and fourthly, a renewed “blind impetus” towards a nuclear future marks a pathway towards increasingly centralized, undemocratic and unaccountable societies, based ever more around paranoid discourses of “security” rather than environmental protection and social justice. It will be interesting to see whether the regional elections taking place today in the German state of Baden-Württemberg usher in a red-green coalition ready to pursue a different kind of technological future.

Interstitial landscapes # 1

I have become increasingly interested in what might be termed “interstitial landscapes”. These include an array of “incidental spaces” or “accidental gardens” that are often ignored or overlooked. These spaces exhibit ecological assemblages or natural formations that have developed independently of “design” as conventionally conceived. Examples of “interstitial landscapes” might include empty lots, the sides of railway lines or even micro-niches such as walls or gutters. Since the late 1960s a number of artists have responded to these types of marginal spaces as a way of exploring the meaning of urban space in new ways. Since the 1950s urban ecologists, and especially botanists, have been studying “ruderal” sites characterized by adventitious plants and new landscape typologies. In a European context these sites were originally associated with catastrophic events such as the creation of “bomb sites” through aerial warfare but by the 1970s the effects of de-industrialization and demographic decline were also leaving their mark on urban landscapes.

Among the artists who have studied these marginal spaces Gordon Matta-Clark is especially interesting. In the early 1970s Matta-Clark became intrigued by New York City’s periodic auctions of so-called “gutterspace” comprising seemingly unusable fragments of land. He acquired 15 small sites as the basis for a project entitled “Fake estates” which involved taking photographs, along with the acquisition of deeds, surveys and other documentation to produce a detailed visual and cartographic compendium of marginality. Though never shown during his lifetime these photographs have occasionally been on public display such as the Queens Museum, New York, in 2005 and more recently as part of an excellent show at London’s Barbican (which also features two other pivotal figures from the 1970s New York cultural scene, Laurie Anderson and Trisha Brown).

Feeling inspired by seeing Matta-Clark’s works at the Barbican I wandered around my own neighbourhood in north London and took some photographs of anomalous spaces or “weeds” that had colonized the streets. I became conscious of the precarious balance between a certain kind of order reflected in maps, title deeds and other records of spatial structure and ownership, and a kind of largely unnoticed and ubiquitous disorder reflected in specks of rust, litter, plants, crumbling walls, peeling paint, broken tiles and other elements of everyday space. In particular I observed a precarious space that extends beyond clearly demarcated lines such as homes or shop fronts where the jumbled and increasingly vague responsibilities of municipal authorities, utility companies and others combine to produce a neglected zone. What does it mean to say that a space is unimportant? Or that a plant growing by the roadside is just a “weed” with no aesthetic or cultural value?

Where does the city end?

How do we know we have reached the edge of the city? Is it an aluminium sign? Is it a thinning out of buildings until there is little but woods and fields? Or is it an abrupt shift to small towns and villages dotted across the landscape? Perhaps it is really none of these things since the city, or at least “urbanization”, is now practically everywhere. In his book The urban revolution, first published in 1970, the French urbanist Henri Lefebvre makes a distinction between “city” and “urbanization”. “Society has become completely urbanized,” writes Lefebvre, “This urbanization is virtual today, but will become real in the future”. In the forty years since Lefebvre wrote these words the pace and scale of urban growth has accelerated along with the more ubiquitous dynamic of “urbanization”. The impetus towards “complete urbanization” can be conceived as a multi-faceted development that ranges from infrastructure networks to the spread of new ideas. The urban and the rural have become increasingly difficult to differentiate despite the powerful cultural resonance of this distinction. We can never really understand cities as simply “things in themselves” since they are manifestations of broader processes of change, connection and re-combination. Cities are just a particular form of urbanization.

Untitled with rain

John Fahey’s instrumental Untitled with Rain, timing in at just under 24 minutes, is a mesmerizing piece. It is included on his final album Red Cross recorded shortly his death in 2001. The sparse instrumentation consists of guitar, bass and organ, accompanied by the sound of rain. Fahey’s plaintive guitar playing builds an introspective mood, at 2’30” the organ sound begins to shimmer and becomes louder, heightening a sense of emotional tension, at 4’36” a voice calls out “Hi there John” and the atmosphere of a small club is invoked on a dark rainy evening. At 6’32” some gentle chimes denote the minimal use of percussion and by 6’52” the music has faded to nothing – we are left with complete silence for nearly 17 minutes. Yet symbolically we are still within Fahey’s musical space just as John Cage brilliantly recast the meaning of silence with his 4’33” in 1952. Fahey’s Untitled with Rain is a meditation on presence and absence. It is an ambient soundscape that draws everything in and then vanishes to leave only our imagination.

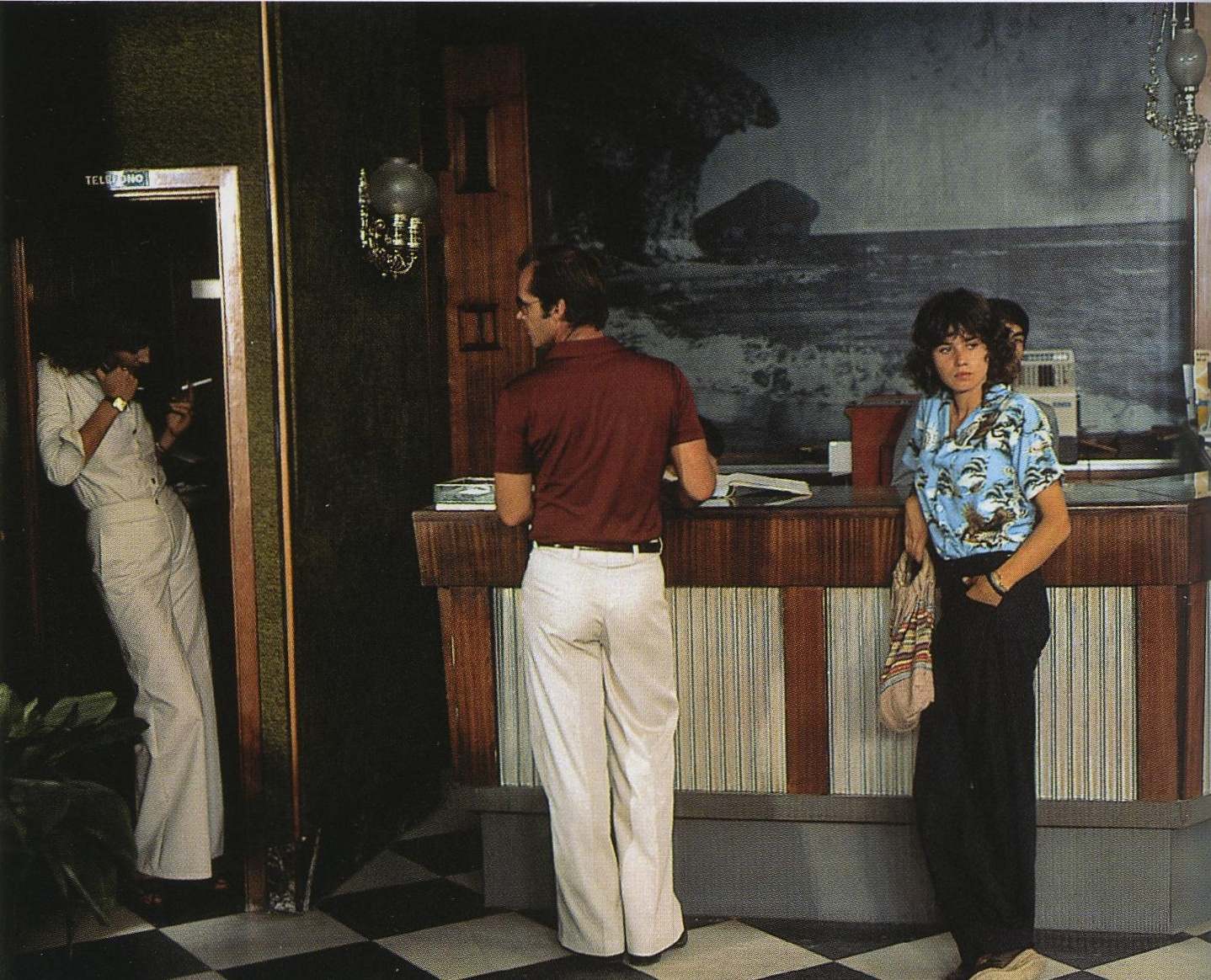

The Passenger

After reading Maria Schneider’s obituary yesterday I decided to watch Michelangelo Antonioni’s film The Passenger (1974), where she appears as a young architecture student who befriends a journalist, David Locke, played by Jack Nicholson, who has exchanged his identity with another man after finding him dead in a small hotel in North Africa. After taking his new identity Locke begins to enter the dead man’s life by keeping various appointments in his diary, including business meetings across Europe. In so doing Locke discovers that the man was in fact an arms dealer and that he has now immersed himself in the politics of a civil war, which he had previously only engaged with as a journalist. By the use of flashbacks, and in one instance a real documentary sequence, the film hovers between past and present, and between different strands of reality.

Although I have seen The Passenger a couple of times before it remains one of the richest and most complex of Antonioni’s movies with fascinating location shots in Chad, Munich, London and Franco era Spain (including sequences in Andalucia and Barcelona). From the opening scenes we find Antonioni’s characteristically sparse and geometric use of landscape, ranging from the dune formations of the Sahara to London’s Brunswick Centre. There is an intricate attention to detail such as the ambient sound of whirring fans, the architectural façades of Antoni Gaudí or swirls of dust in an orange grove, that evoke the fog of his earlier film Red Desert (1964).

Perhaps the most striking sequence is when they leave Barcelona in an open top car, driving at speed into the Catalan countryside. “What are you running away from?,” asks the student. “Turn your back to the front seat,” replies Locke, and we see her delighted expression bathed in the dappled sunshine of the roadside poplar trees as she observes the road receding into the distance.

The Passenger is about identity and the ultimate impossibility of escaping from ourselves. This at times obtuse yet technically brilliant film uses landscape to great effect to evoke a spectrum of emotions from wonder to despair: Antonioni is intrigued by the psychological “effects” of landscape and the possibilities for space to elicit unexpected responses from his cinematic protagonists. The pacing of the film is slow: the tragic denouement, for example, is conveyed by a remarkable seven-minute tracking shot that brings together all of the main characters. Yet the slowness of the film is vital to its effectiveness as an exploration of mood, place and the subtleties of human relationships.

Between science and aesthetics: the ecological art of Ulrike Mohr

On 4 April 2006 the demolition of Berlin’s Palast der Republik was halted for one day. The artist Ulrike Mohr was to be allowed to undertake a systematic botanical survey of the trees and other plants that had colonized the roof since German reunification. This vast public building had fallen into a state of disrepair since the early 1990s and had become a kind of ecological laboratory for the study of urban change. Small fissures in the concrete and bitumen had allowed an accumulation of organic matter, and in addition to the typical adventitious species of plants one might encounter growing out of cracks in roads or pavements there were now well-established trees such as birch, poplar and sallow, indicative of the early stages of a rooftop forest in formation.

Mohr’s investigation of the ecological consequences of urban entropy entitled Restgrün [Remaining green] raises important questions about the intersection between science and aesthetics. The study of abandoned spaces is not just a question of aesthetic curiosity but also holds significant scientific implications: in the case of Restgrün, for example, one of the trees found growing on top of Berlin’s Palast was Populus nigra, which is on the Red List for regionally endangered species.

For the 2002 project Versuchsanordnung Acer Platanoides [Test set-up Acer platanoides] Mohr chose a six-meter-high Spitzahorn, or Norway Maple, Acer platanoides, growing in the Künstlergärten Weimar, and stitched together the tree’s leaves with red thread so that they were unable to fall during the autumn. The entire leaf structure was then carefully removed by crane and put on public display in Mohr’s first solo show at the Kunstverein Hildesheim. With this “ecological interruption” Mohr performed a non-utilitarian intervention in nature: we are invited to reflect on the meaning of nature through its unexpected cultural appropriation so that there is both a temporal and spatial dislocation in a largely unnoticed yet remarkable everyday transformation: the annual shedding of leaves by a maple tree.

This notion of time in nature — referred to in ecological science as “succession” — connects with a fascination with the spontaneous re-arrangement of nature. Mohr plays on the boundary of human intervention in nature in two ways: first, by simply observing nature its meaning and significance change, bringing mundane elements such as a common tree or an assemblage of weeds into a profound form of aesthetic engagement; and second, by simply focusing on one element of nature and performing simple modifications, we contend with the scope and complexity of our relations with nature as an extension of ourselves. In this last sense, Mohr brings her exploration of nature into a historically specific scientific frame: her works connects powerfully with the development of urban ecology in post-war Germany as a form of intricate and passionate engagement with nature in cities. In particular it engages with the diversity of potential biotopes or habitat niches associated with the type of everyday instances of nature that have been largely neglected by mainstream ecological science.

Among the most ambitious of Mohr’s works is the 2003 large-scale tree-planting project 750 Kiefern in militärischer Anordnung/Konversionsgelände Wünsdorf [750 Pines in military formation / Conversion area Wünsdorf ] in which hundreds of pine saplings that had sprouted spontaneously in the parade ground of a former Russian military barracks in Wünsdorf were dug up, measured and replanted. The trees were arranged in five precise formations of 150 trees, with the tallest trees placed at the front of each of the blocks to suggest an ironic confluence of forestry plantations with military discipline. Photographs of the site from above reveal the ambitious scale of the project, and also its spatial accuracy, so that the young trees in combination with their supporting wooden posts resemble a battalion of soldiers standing to attention. This is, above all, a landscape of control: an attempt to regularize nature that connects with the historic purpose of the site as a training ground for military discipline and the exercise of state power. After the completion of the project the site was allowed to revert back to a process of natural succession towards “secondary woodland” so that the work connects both with a sense of ecological time and also historical time since all cultural or institutional forms are temporally limited in their scope.

The tree planting also signals a counterpoint to Joseph Beuys’s mass action entitled 7,000 Eichen [7,000 Oaks], installed between 1982 and 1987 for Documenta 7, where the placing of these trees alongside upright basalt columns was linked with an ecological critique of modernity in the context of pollution-induced Waldsterben [forest death], and also the nascent German green movement with which Beuys was closely involved. What clearly differentiates the work of Mohr from that of Beuys is her rational engagement with urban nature as an arena for cultural discourse rather than a hidden repository for ecological mysticism. It is Mohr’s critical distance from the German romantic tradition that renders her work especially interesting in an international context.

The art of Ulrike Mohr is characterized by an attention to detail: not just the subtle textures of everyday things, but also an attempt to uncover relationships between aesthetics and science, and between past and present. Her interventions break with neo-romanticist associations and are suggestive of a cultural synthesis with nature that is free from the baggage of transcendental meaning. Her interactions with nature and landscape are far removed from the heavy symbolism of some artists (the work of Anselm Kiefer, for example) or the shamanistic utterances of Beuys and his followers. In the work of Mohr we find a subtle irony, that provides new insights not through further layers of mystification, but through a calm insistence on the social production of meaning.

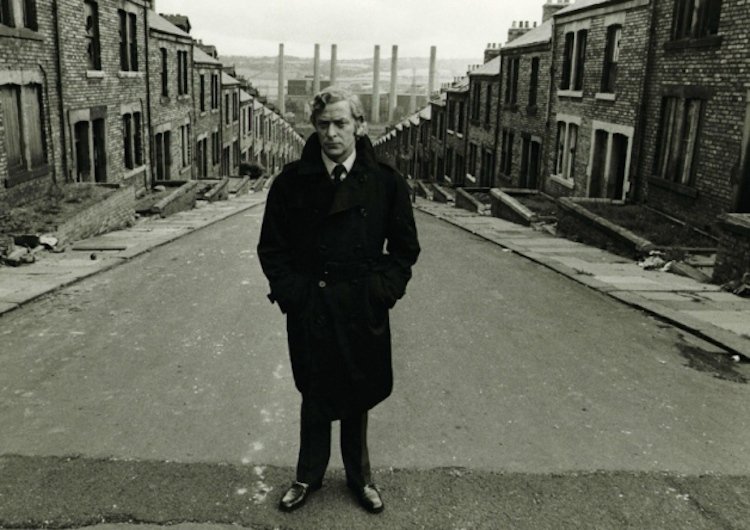

Of time and the city

There is something mysterious about Terence Davies’s Liverpool from the outset: at the heart of this cinematic meditation on the city, released in 2008, lies a tension between urban change as a process that is brutal and unremitting and the persistence of memory as something that is delicate and filamentary. Memories become maps through places to which we can never return in a world that is changing all about us.

In Of time and the city Davies presents us with a wondrously idiosyncratic and elegiac journey that is filled with anger, joy and despair. Davies becomes the “angel of history” hovering over Liverpool, alternately caressing his troubled city or pouring scorn on the forces that have brought the city to its knees. The film is punctuated by quotes from poetry, literature and philosophy that are narrated to us by Davies with a sense of staccato urgency: poignant lines chosen from Chekhov, Engels, Joyce and others inform us that this is a serious film from the outset. This is not a film that panders to an existing audience but one that seeks to create a new one. Davies is not making a pitch to our touristic curiosity nor is he using the city in a narrowly didactic sense. This is a deeply personal mode of documentary film making that is imbued with a profound sense of emotional intimacy.

Like Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel according to St. Matthew [Il Vangelo Secondo Mateo], released to general amazement in 1964, Davies uses music to sublime effect. Both Pasolini and Davies select music that through its apparent incongruity generates a powerful sense of authenticity and immediacy: faces, images and landscapes are dramatically transformed into far more than their mere physical presence as stones, bricks or flesh. In Of time and the city Davies furiously juxtaposes music and place to transcend the petty cruelties of organized religion or the grinding toil of working-class life. Decaying housing estates are set to Bacarisse; cranes and industrial architecture to Mahler.

Davies reserves his real scorn for the British establishment in all their ineptitude and mean-spirited mediocrity. He exposes the flummery and sexual hypocrisy of organized religion with relish. He excoriates the monarchy and other archaic forms of gluttony that feast on the goodwill of ordinary folk. As we see newsreel footage of the royal marriage — “Betty and Phil with a thousand flunkeys” — and the gilded carriage passes through cheering crowds Davies reminds us that “Britain had some of the worst slums in Europe”. His droll disdain for the establishment is also extended to its would-be cultural assassins such as The Beatles who are rendered little more than a ghostly and ironic presence. Just as Joe Strummer rejected “phoney Beatlemania” back in 1977 Davies now derides the “fab four” as looking like “a firm of provincial solicitors” — “yeah, yeah, yeah” indeed.

As for post-war architecture Davies notes with acerbic understatement that “Municipal architecture, dispiriting at the best of times, but when combined with the British genius for creating the dismal, makes for a cityscape that is anything but elysian”. These would-be utopias had by the early 1970s become spaces of decline and emptiness scattered with broken glass and overlooked by boarded-up windows. Instead of utopia we got a city in a state of retraction and disorder. “We hoped for paradise; we got the anus mundi”. These new architectural forms were often poorly constructed and maintained, displaying but a faint echo of their exemplary prototypes in European cities and containing their own versions of built-in senescence to match the social and political neglect of their new occupants.

Liverpool has been the traumatized epicentre of Britain’s full-scale industrial decline since the 1960s with a greater population loss than almost any other British city. Unlike former industrial cities in Europe such as Hamburg or Milan, which have successfully rebuilt themselves, it is apparent that Liverpool’s contemporary renaissance is slender indeed: not a replenished civil society or newfound industrial acumen but a retail desert populated by gaggles of drunken figures tottering around beneath the glare of streetlights and security cameras.

The final tracking shots of gentrified docks and warehouses evoke a sense of placelessness: these waterside developments with their familiar “brandscapes” could be any one of a number re-fashioned industrial waterfronts from Baltimore to Buenos Aires. “As we grow older,” observes Davies, “the world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated…and now I’m an alien in my own land”. We float with Davies across neon-lit landscapes or hover over boutiques and wine bars that were once factories or churches. At the close of the film we encounter Liverpool “gathered in at gloaming”, a myriad of strange illuminations in the failing light. What has Liverpool been? What have we been?

Beautiful and scathing in equal measure Of time and the city must surely rank as one of the best films about a British city that has ever been made. But the film is not simply about Liverpool: it is also a mordant response to the failures and disappointments of post-war Britain and a bittersweet exploration of the delicate connections between memory and place that anchor our sense of individual and collective identity amidst the tumult of historical change.

El sol del membrillo [The quince tree sun]

Víctor Erice’s documentary El sol del membrillo [The quince tree sun] (1992) is a simple idea: we follow the artist Antonio López Garcia’s attempt, during the autumn of 1990, to paint a quince tree in his back garden. The film seems to emerge quietly in real time on a late September morning as we see the artist arranging his canvas and inspecting the tree; the only sounds are largely ambient, the rumble of a train, a radio playing and incidental moments like removing the stopper from a bottle of turpentine. With gentle time-lapse photography we observe the emerging canvas over coming days; preparation, patience and detail are interspersed with reminiscences with an old friend who comes to visit. Together, they marvel at the beauty of the tree: the shape, the colours and the fullness of the fruit. Garcia is consistently perplexed by small variations in sunlight and the fact the tree itself is changing over time: he paints small white markers on the leaves and fruit to trace changes in the shape of the tree and the gradual sinking of the branches under the weight of the ripening fruit. “I follow the tree,” he remarks, but the weather worsens, the sky is overcast and his sense of frustration grows.

It is late October and we see the stairwell in his house illuminated with light, set to the music of Pascal Gaigne — very little incidental music is used in the film but it drifts through specific scenes to mesmerizing effect. Garcia has now abandoned his attempt to paint the tree and switches to a drawing instead which he refers to as “a map of the tree”. He contrasts his approach with other artists who work from pictures or photographs since he wishes to avoid “aesthetic games” and struggle directly with the impossibility of representation. By mid-November Garcia describes the tree as being in “full decadence” and he picks up the first fallen fruit on the ground and smells it; the leaves of the tree are now beginning to yellow with small blotches and imperfections spreading. “It’s over,” he declares, and he collects up his things, leaving the garden strangely empty for the first time.

Garcia now poses for another artist, his wife María Moreno: he lies on a bed observing a cut crystal and falls into a deep sleep disturbed by vivid dreams. We see shots of Madrid at night: flickering television screens and moving traffic are interspersed with a bright moon and drifting clouds revealed in all their detail. He narrates a strange dream where he is standing with many others and sees his quince tree now transposed somewhere else. We see the tree next to a camera, the fallen fruit lying under the glare of a powerful light. “Dark spots slowly cover their skin in the still air…Nobody seems to notice the quinces are rotting under a light…turning into metal and dust”. And then the garden is shown next spring with shrivelled and misshapen fruit lying beneath the tree but new buds becoming visible on the branches.

This is a remarkable film of almost unimaginable subtlety that emerges from an intense encounter between an artist and his struggle to convey what lies in front of him. In the end it is time and light that defeat him: the growing tree is itself impossible to capture effectively and every small play of light continually transforms the appearance of the tree. Of course this is not a documentary in the conventional sense but something far more interesting: an exploration of the intersection between an outer world of beauty and decay and an inner world of dreams and imagination.

Bremen’s elephant

Near the centre of the northern German city of Bremen is a large elephant made of bricks. This imposing ten-metre high structure — designed by Fritz Behn — was completed in 1931 as a monument to the German colonies which then included Cameroon, Togo, Deutsch-Ostafrika [Tanzania], Deutsch-Südwestafrika [Namibia] and several islands. For decades the “Reichskolonialehrendenkmal” stood as a powerful symbol of German colonial ambition that spanned both the Nazi era and the post-war period of reconstruction: an aesthetic continuity that stands in sharp contrast to the hurried erasure of the DDR.

In 1988, however, a metal sign was created next to the elephant by the youth wing of the Bremen metal workers union in support of the Anti-Apartheid movement. In 1990, with the celebration of Namibian independence from South Africa, the elephant itself was re-dedicated as the “Bremen anti colonial monument” thereby attempting to invert its historical meaning yet retaining the original design. And in 2009 a new monument was created next to the elephant to the victims of German genocide: between 1904 and 1908 over 70,00 of the Ovaherero, Nama and Damara peoples of Namibia were murdered followed by an intensified phase of racial segregation that pre-figured the development of Apartheid in South Africa. In contrast to the elephant the genocide memorial adopts a more abstract design reminiscent of land art or street installations: a horizontal array of simple elements such as rocks and stones in the place of vertical bombast.

This assemblage of memorials and plaques reveals that the German colonial presence in Africa was not a minor element in European history: we now know that many of the perpetrators of early twentieth-century violence in Namibia and elsewhere would go on to play a significant role in Nazi expansionism in Europe. In the place of the Herero were the Slavs and others to the east, where an envisioned settler landscape bore parallels with European sequestration of fertile lands in Africa. What is especially interesting about Bremen’s elephant is that it poses the possibility for changing the meaning of public monuments: it allows remnants of the past to become incorporated into new understandings of history. How many other elephants remain unnoticed or unchallenged in European towns and cities?

The magic of emptiness: reflections on a Berlin corner

Since the summer of 2004 I have got to know a corner of Berlin very well, where the Chausseestrasse, running north-south, meets the quieter Linienstrasse from the east. In 2004 this corner of Berlin, where the district of Mitte, the centre of the former east Berlin, meets “Red Wedding”, the traditional bastion of working-class Berlin and one of the poorest districts of West Berlin, was surrounded on three sides by “empty spaces” where the Berlin Wall had once been. The large plot to the east of the Chausseestrasse had become a vibrant meadow full of birds, butterflies and wild flowers, dominated by brilliant blue patches of Echium vulgare which goes by the extraordinary English name of Viper’s Bugloss (it is also known in German as Snake’s Head or Natternkopf). On the north side of the street a drab municipal park to the south an ecological paradise.

One summer evening I stumbled across an extraordinary moth that I didn’t recognize at all: I carefully took a photo and let it go. It turned out to be Cucullia fraudatrix, an eastern European species at the extreme west of its range in Berlin, that normally flies over dry grasslands. But is not only nature that fascinates me in these places: objects and fragments also become part of this spontaneous landscape where rusting pieces of metal appear perfectly placed as if in an urban sculpture garden.

By 2010, however, these open spaces are in accelerated retreat: to the west of the Chausssstrasse a vast new office block is close to completion that will house the headquarters of the German security services. Next door, in pristine brick, is a new building belonging to the Berlin water works. Two normally hidden infrastructural arms of the state now lie side by side, like shiny mushrooms sprouting from their tangled mass of networks hidden from view. And the urban meadow on the east side of the street, that I had explored over several summers, is now fast disappearing: about one-third has become a petrol station and another third a parking lot.

Returning yesterday I could no longer see the meadow from the street. It is now surrounded by a high wooden fence: a moment of enclosure before its final and inevitable erasure. I took some photos as suspicious drivers entered the petrol station. Somewhat disheartened and trying to keep warm in sub-zero temperatures I crossed the street and noticed a wire fence next to wooden billboards. There was a small gap and I stepped through. A tangled mass of plants reached above head height and the ground was hard with frost. After taking a few paces I realized that this was just an “antechamber” to an extensive ribbon-like void space stretching hundreds of metres where the Wall had once been. It was like entering a series of rooms each more mysterious than the last. A discarded bottle lay among dead leaves and there were some occasional strips of red tape: people have been here.